Image courtesy: Yogesh Maitreya

Image courtesy: Yogesh Maitreya

In 1928, Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar was asked to preside over a meeting to consider building a temple dedicated to Chokhamela, a 14th-century mahar caste saint-poet from Maharashtra. Ambedkar knew of the songs and the abhanga style of poetry popularised by the Bhakti movement in Maharashtra and beyond. His own father was a Kabirpanthi, or follower of the 15th-century mystic poet, Kabir. Yet, on the temple proposed for Chokhamela, he presented a sceptical—though still radical—opinion about saint poets and the Bhakti movement.

“…the struggle of the saints did not have any effect on society,” Ambedkar famously told the gathering at Trymbak near Nashik in Maharashtra. “The value of man is axiomatic, self evident; it does not come to him as the result of the gilding of Bhakti,” he said. “The saints did not struggle to establish this point. On the contrary their struggle had a very unhealthy effect on the Depressed Classes.”1

This address by Ambedkar is recorded in the 17th volume of his Books, Writings and Speeches, published by the Government of Maharashtra in 2016. It records him saying that the Bhakti saints “…provided the Brahmins with an excuse to silence them [the Depressed Classes] by telling that they would be respected if they also attained the status of Chokhamela.”

Also read | Raja Dhale: A Renaissance Figure in Dalit Literature and Art

By 1928, a new class of intellectuals, including Ambedkar, had emerged in India’s political and social life. Their commentaries on organised religion were radical and profound. They had started to reject outright the oppression that stemmed from religion. Also, by then, religion had become a matter of inquiry and interrogation; it was no longer considered a subject of just spirituality or romanticism. These changes were inevitable in the wake of scientific innovations and technological advancements of the age. This was the context of Ambedkar’s Trymbak address.

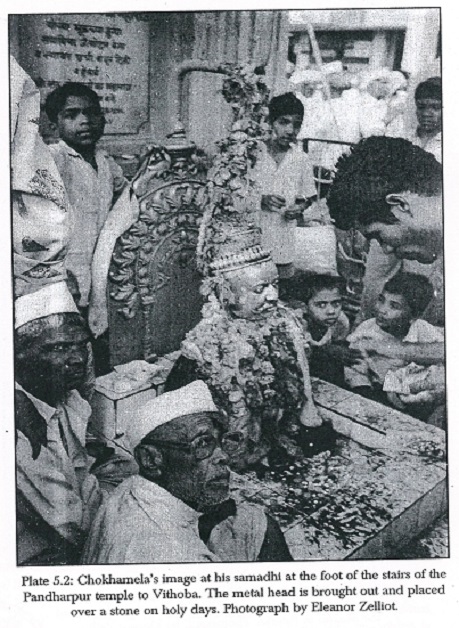

Even ninety years later, Chokhamela is only a small reference in the long history of Maharashtra. His works have not much currency among intellectuals or scholars. The American historian of South Asia Eleanor Zelliot has aptly captured the reasons for this. She says in the book Untouchable Saints, edited by her and Rohini Mokashi-Punekar and published in 2005 by Manohar, that “Those of Chokhamela’s caste now have by and large rejected him, and for two reasons: the Buddhist conversion initiated by Dr BR Ambedkar in 1956 has meant a rejection of most things Hindu on the part of many. Second, Chokhamela himself, in one abhanga, said that he was Untouchable because in a previous life he had insulted Krishna, and this karmic reasoning is totally unacceptable to Untouchables now.”2

Yet, Chokhamela’s 13th to 14th-century abhangas, and the songs of other Maharashtrian dalit-bahujan saint-poets from the Bhakti movement, offer a complex and crucial narrative to understand the inception and growth of resistance in future dalit traditions and movements. This is specially significant in the context of the Varakari tradition prevalent in Maharashtra. Every year, after the season’s first seeds have been sown in farms, devotees travel on foot—a journey called Vari—to the temple dedicated to Vitthal or Vithoba.

Consider the influence of this tradition in rural Maharashtra. Rohini Mokashi-Punekar, a professor of English at IIT Guwahati says in Untouchable Saints, “The Varkari cult is clearly the most quietly influential mass movement of rural Maharashtra.” She records the most striking feature of this cult as the absence of a priest to mediate between the devotee and his bhakta. “…no rigorous individual ritual such as elaborate pujas are needed. It is a code most suited to poor, illiterate, labouring castes and peasants who can afford neither money nor leisure nor learning… For the fifty odd saint-poets belonging to this tradition, drawn from almost all castes of the region of those times, the abhanga is the most important medium of comprehending, reaching, and expressing the sense of divine mystery and joy; it is also the means of articulating pain and anger against injustice.”3

These fifty or so saint-poets were predominantly from dalit-bahujan castes and Chokhamela was the most prominent among them, and the most notable from the mahar caste among the Bhakti poets of Maharashtra. His continuing popularity is therefore a creation of a dalit-bahujan literary imagination. The narratives they crafted did not explicitly pursue the path of annihilation of caste. Yet they exercised their agency in the domain of literary imagination as equals. To be able to enter and participate in this domain, especially as it pertains to religious discourse, cannot be trivialised. For this very domain had been distorted by brahminical narratives and had rejected them.

Also read | Why Songs Are Sabotaged: Dalits and their Music

After Chokhamela’s arrival—himself was a labourer—fresh dalit-bahujan metaphors and perspectives emerged for referring to god. “It is said that Chokha died along with another Mahar labourer when a part of the wall they were repairing in the town of Mangalvedhe collapsed on them,”4 the editors of Untouchable Saints record. His abhangas have a dalit literary pespective that is never found in literary works written by brahmins of his time, nor in brahminical narratives.

He writes in Abhanga 284:

He pulled a wall for

Dnyaneshwar; made Changdev

famous; weeded the beds

for Savata the gardener

and fired pots for Gora.

He loves more than his own self

the goldsmith, the cobbler

and Namdev, the tailor.

He grinds the grain

at Jani’s home, sweeps the dirt

and brings the cow-dung in.

Says Chokha, he is so tender,

his devotees know him

as a fond mother.

Study this abhanga closely. Chokhamela has radically replaced the existence of god into everyday chores, making his verse the antithesis of brahminical narratives. This is the reason for his verses acquiring mass appeal across castes. He associates the image of god with the process of dalit-bahujan labour and occupations, which fulfil the material functions of society.

In the twenty-first century, Chokhamela may not appear radical, but for when he wrote, the 14th century, his ideas are strongly iconoclastic. The cruel social circumstances manufactured around idea of religion by brahmans, who had glibly started to give a brahminical veneer to all dalit-bahujan ideas—including their ideas of religion and traditions.

Not only does Chokhamela reject the existence of brahminical scriptures and their gods but also fought those notions by bringing in the Buddhist dialectic of impermanence. In another abhanga, number 2825, he says:

The Vedas and the shastras

polluted; the puranas inauspicious,

impure; the body, the soul

contaminated; the manifest

being is the same.

Brahma polluted, Vishnu too;

Shankar is impure, inauspicious.

Birth impure, dying is impure.

Says Chokha,

pollution stretches

without beginning

and end.

For his time or any, these words rejecting the vedas and the shastras are no less than revolutionary. Besides, Chokhamela equates the existence of untouchables—the mahars were regarded as Untouchable in his time—with god.

An explanation of his use of Buddhist dialectics is to be found in Chokhamela’s abhanga 279:

Five elements compound the impure body;

All things mix,

Thrive in the world.

Then who is pure and impure?

The body is rooted in impurity.

From the beginning to the end,

Endless impurities

Heap themselves.

Who is it that can be made pure?

Says Chokha,

I am struck with wonder.

Can anyone be beyond pollution?

The idea of pollution and purity is a product of the wily imagination of brahmans. Here, he has dealt with it in a radical scientific temper that is as categorical as the laws of physics. This is important, for the scientific temper is the premise on which the dalit literary imagination stands and thrives till today. This creative imagination was not limited to Maharashtra. In roughly the same period came Ravidas, the most radical and scientific saint-poet in north India. It is yet Chokhamela’s voice that was the breakthrough cry in the dalit literary imagination. Today, his abhangas are on the lips of people across castes from interior Maharashtra, where they are sung during the Vari of Pandharpur.

Also read | Wamandada Kardak: Singing a Casteless Republic into Being

Earlier this year, this writer said in the Economic and Political Weekly (From Shahiri to Sahitya, February 2019) that before the advent of dalit literary forms as a movement, Ambedkari Shahiri and its sound became the medium for dalits/Ambedkarites to understand, recognise, articulate and assert their anti-caste agency. An anti-caste consciousness grew in the community and seeded the imagination of dalit writers. In the 1970s, they produced a body of literature that was called “dalit literature”. “In the emergence of dalit literature, the sound of Shahiri played a crucial role as it challenged the domains of brahminical consciousness; dalit literature became the later manifestation of this challenge as well as a product of the sonic imagination of Ambedkari Shahiri.”6

To understand Chokhamela’s abhangas it is important to penetrate the context of the effect his music and poetry had, and to discern its popularity. His work has scaled the temporal barrier to transcend centuries and it took a giant leap when it comes to inquiring into brahminical scriptures and religion.

He was inclined towards acceptance by god and brahminical agency, but in his abhangas Chokhamela simply exercised his rights as a human being. A right which was denied, crushed and snatched from him and his community by brahmins.

Notes:

1BAWS, page 8-9, Vol 17 Part three, Government of Maharashtra, 2016

2Untouchable Saints, edited by Eleanor Zelliot and Rohini Mokashi-Punekar, Manohar, 2005

3Id.

4Id.

5All Abhangas are from collected edition, Shri Sant Chokhamela: Charitra ani Abhang (rept. 1998) by S.B. Kadam

6From Shahiri to Sahitya, Yogesh Maitreya, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 54, Issue No. 6, 09 Feb, 2019