India has had numerous epiphanic moments when a singers’ songs have been sabotaged, when singers have been punished for their writings and the like. Irrespective of which political party is in power, the brahminical ethos has consistently been upheld in Indian policies and governance. That is why the state perceives dalit music and musicians in particular as threats.

Socially conscious musicians from the oppressed communities, who envision an equitable, just and fraternal society have often face implicit or explicit violence, especially if their work carries tremendous mass appeal.

This has especially been the case of dalit shahirs living under the Indian state. However, whatever the state’s perception may be, India remains divided into thousands of castes. This has come in the way of such epiphanies — though there have been numerous — from crossing a certain threshold and taking the shape of a social revolution.

Also read | Raja Dhale: A Renaissance Figure in Dalit Literature and Art

Nevertheless, the songs of dalits and dalit shahirs still bear the potential to change how we think as a society and usher in such a revolution. It isn’t just the music — the very experiences these songs sway to carry the potential to shake up society. Most of it talk about the life history of dalits, and that is what brings most of dalit resistance music into existence. These experiences give this music a quality that seeps right into the heart, even though they unsettle, rather than entertain, listeners. According to me, this is the unique ability of dalit shahirs to touch a listener’s conscience.

The anti-thesis to dalit shahir’s creations are songs — especially from Bollywood — which entertain and thereby mar the sense and ability to perceive beauty in the desire to form an equal, just and fraternal society. Even the songs of love imagined by dalit shahirs are woven with the thread of logic and the needle of their vision points towards an equitable society.

Hear, for example, this song written by shahir Shantanu Kamble:

With your anklets clinking, you come by the path of equality

Breaking shackles, you come, you come

People are caged in the mansion of caste

Such is the poison that destroys generations

People with flesh and bones aren’t seen

People become strangers to each other

You come, breaking and thrashing the walls of caste.

Two punch lines written by him have been, for over a decade, the anthem of protests in Maharashtra:

Dalita Re Halla Bol Na

Shamika Re Halla Bol Na

O dalits, Storm the citadel!

O workers, Storm the citadel!

Many such songs written and performed by Kamble have created a perceptible stir among youngsters and in the wider society. They are not just powerful when heard but rousing, and can make one’s blood boil.

The impact is such due to the music Kamble inherits; but it is more on account of the fact that his songs convey the truth — unapologetically, daringly. His words and songs have the capacity to elevate the understanding of a listener. They can lift one from the mundane and reactive plane to the radical and rational level. The brahminical state has never wanted this to happen, because it uses its cultural industry to prohibit the development and arrival of a radical and rational republic. Songs which pave the way for a radical and rational society are a threat to the brahmin state.

Also read | Wamandada Kardak: Singing a Casteless Republic into Being

Kamble died last year in Nashik: “In 2005, he [Kamble] was accused of having links with Naxalites. He was put into police custody for almost a 100 days. It was a torturous time for him. Eventually, he was acquitted, innocent as he was. But this physically and mentally torturous period seemed to have left an effect on him which is not imaginable by many of us—simply because many of us do not possess the profundity necessary to understand shahirs like him.”1

His ambiguous arrest and the accusations he faced were also attempts to limit the effects of his music. Such draconian moves by the brahminical state to sabotage the music of dalit shahirs only elucidate the strength of their music. The attacks take place precisely because these songs participate in the process of revealing the truth. Coupled with Kamble’s voice, such music dismantles prejudice and discrimination.

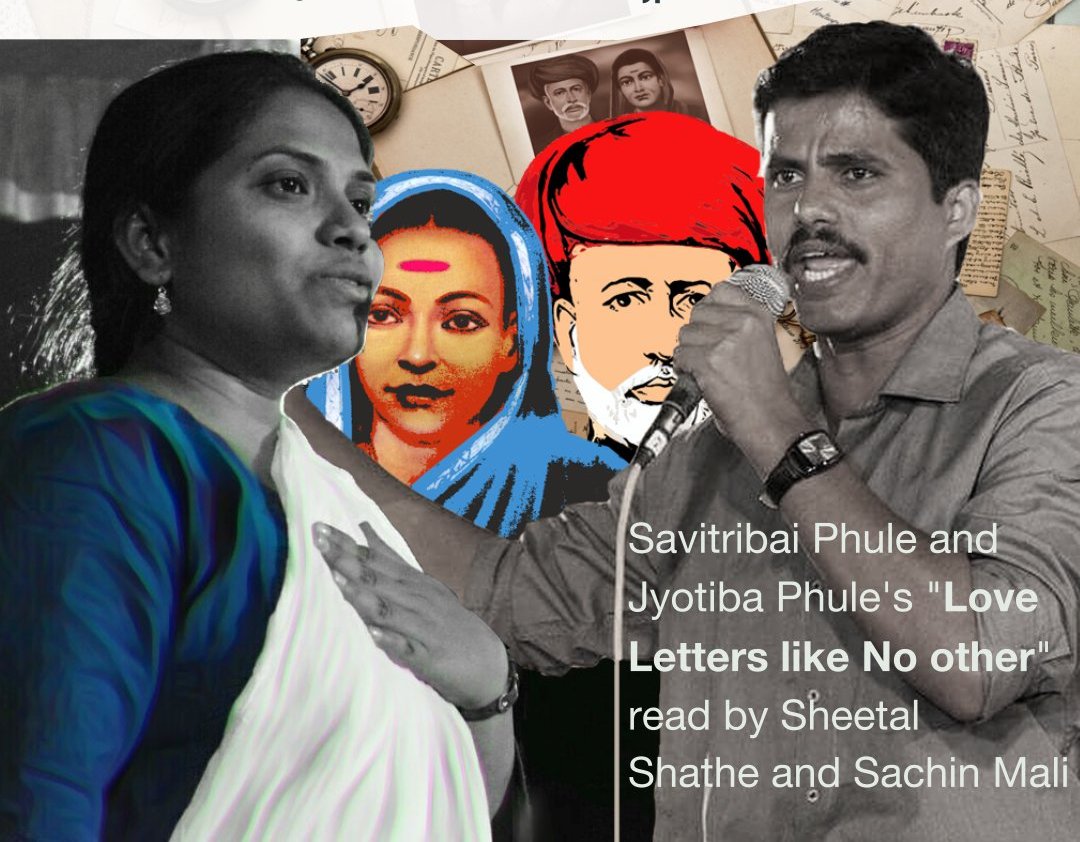

Two years later, in 2011, Sachin Mali and Sheetal Sathe, who were then part of the Kabir Kala Manch (KKM), an anti-caste cultural outfit, came out of hiding. (Other members of the KKM had been arrested by the police under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act or UAPA.)

Sheetal, a brilliant singer, was granted bail as she was pregnant, but Sachin, her husband and a remarkable poet and lyricist, was imprisoned for four years. This disjunction broke the effect of their songs and performances, if it did not affect their spirit to sing their songs against the casteist state in favour of the people, who constitute the real republic.

While in jail, Sachin wrote a collection of poetry and Sheetal kept singing them. One of the most powerful of these is Sampavila Deh Jari:

Even if you destroyed the body

The conscience won’t be destroyed

You, contractors of religion

How would you cease progress.

Sachin Mali has written several such enchanting songs, ceaselessly amplifying the anti-caste aesthetics through his music and spreading awareness about how oppression functions. They also solve the puzzles and conspiracies of history that are not known to ordinary people. In India, the songs of dalit shahirs, their lyrics and music, also explain history in a simpler language. Their is a history that has rarely been sung in popular culture of movies and music albums. Such songs were rendered by Sheetal in her alluring and ruminative voice.

Together, their songs affected people radically but also rationally. No wonder the music from such dalit artists is seen as a threat. It is lethal to discriminatory forces because it has emerged out of an egalitarian ideology.

“Overall, an ideology provides adherents with a picture of the world both as it is and as it should be, and in so doing, [it] organises the tremendous complexity of the world into something fairly simple and understandable,”2 the American political scientist Lyman Tower Sargent notes in his book, Contemporary Political Ideologies: A Comparative Analysis.

This conflict between the world as it is and should be is evident in the rap music of American Black rappers, especially Tupac Shakur’s work. For example, in How Can We Be Free, he writes:

Now I bet some punk will say I’m racist

I can tell by the way you smile at me

Then I remember George Jackson, Huey Newton

And Geronima 2 hell with Lady Liberty.

Tupac was undoubtedly much more socially conscious and involved with the community than many other rappers and this manifests in his songs. The nature of violence, in the context Black rappers work in, has totally different premises and reasons from the dalits. But that violence and punishment surround the lives of Black rappers and dalit shahirs alike is undeniable.

My argument is not to compare Kamble and Tupac, both of whom have experienced oppression and developed an artistic vision to fight it. I want to shed light on the fact that musicians who belong to persecuted and suppressed social groups face violence precisely for envisioning justice and fraternity. If their work has the power to attract and tempt the ears of the public, they are punished for it (Tupac was shot dead in 1996).

Also read | Sharad Patil’s Radical Aesthetics: Never Lose Sight Of An Artist’s Caste

The mass appeal of their songs comes from the fact that they have the potential to deepen the conscience of the masses who are made victims of the propaganda of oppressive regimes.

The popular music only poured emotionality and romanticism into people, trapping them and convincing them to believe that songs are only meant to entertain, soothe a heartbreak, or romanticise the subject. It never gave people access to clarity on history or the modes of oppression in their everyday lives. In this sense dalit shahirs awakened people from the torpor of emotionality and made them socially conscious beings.

It is exactly to prohibit the growth and development of their social consciousness that their songs are sabotaged, time after time.

Notes:

1Shantanu Kamble passes away: Remembering the power, influence of the Dalit shahir’s rebellion, Yogesh Maitreya, Firstpost, dated June 15, 2018.

2Contemporary Political Ideologies: A Comparative Analysis, Sargent, L.T, Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press, 1975.