Inclusiveness has taken many forms in India, but now it has become a rallying cry because it is under attack. May I give you my own understanding of how it became an integral part of our modern identity and came to mean ‘We Indians’. Now that we are being told that India means ‘We Hindus’, and all other Indians are outsiders living here, we need to reaffirm its true meaning and to reject this attempt by Hindutva to divide us.

Our political sense of being one people, became part of us during the fight for freedom led by Mahatma Gandhi. Before that, British rule had cubbyholed us into separate categories, Hindus, Muslims, princely states and so on, to make it more convenient to govern and control us. Divide and rule has always been the policy of empires. The movement for freedom under Gandhi was the first countrywide movement in Indian history, and the first event that can be called national because it cut across all divisions of region, religion, caste and class, language and gender, and united us as one people. It was also the first time in any country’s history that class and mass came together under one banner. It was Gandhi, who, through this recognition and exercise of inclusiveness, created us a nation. Independence only confirmed the fact.

But Gandhi’s concept of inclusiveness was not just political. It had a personal dimension and it was about human dignity. He put it into practice by taking two unusual steps. His first step was to take off the clothes of his class and his privileged upbringing and put on a loincloth and to live half-naked thereafter, so that he could lessen the distance between himself and those who lived in conditions of dire poverty and want. He correctly recognised that the majority in India were not Hindus. The majority were the poor. The langot was a symbolic gesture one might say, but it turned political attention in a direction it had never gone before.

The second step he took toward inclusiveness went further, by focusing on untouchability. At a time when it was routinely accepted, he declared it a crime and his fight against it took first place on his agenda, more important than the fight for freedom. Typically, his campaign against it began at home. Everyone in his ashram had to do the work that untouchables, as they were then called, were condemned to do. Ashram members had to clean their own toilets and carry and dispose of their own shit. It was his conviction that only by performing these tasks ourselves could we revolutionise the caste-ridden Indian mind. We see a reverse echo of this today with a Dalit movement telling upper castes that they will no longer skin and dispose of cow carcasses, and that caste Hindus must do the dirty work themselves. He also led the battle for Dalit entry into temples, defying the wrath of Hindu orthodoxy. And, of course, Hindu-Muslim unity was his passionate concern. With his profound respect for Islam and all religions, he included their hymns and prayers in his own prayer meetings, and gave the country a new mantra: ‘Ishwar-Allah tero naam, sab ko sammati de bhagvan.’ It was this that made Hindu-Muslim rioters in Noakhali stop their savage rioting and lay down their arms when he went among them during the terrible days that preceded independence. Gandhi showed Indians what he meant by inclusiveness. His chosen heir, Jawaharlal Nehru, made it the meaning of India and the guiding principle of his governments. The Hindutva mentality murdered Gandhi, and now it is murdering Nehru by wiping him out of history.

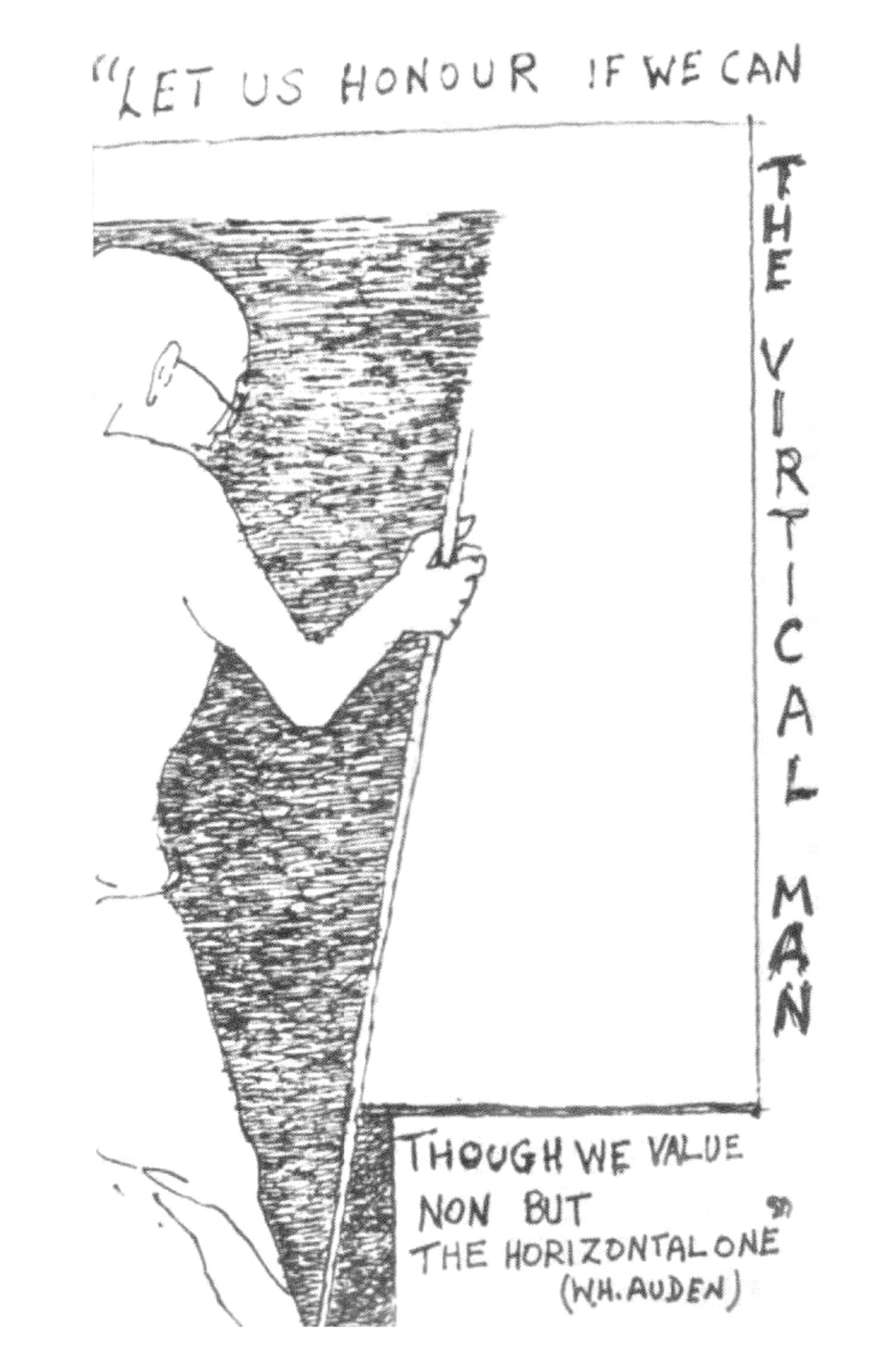

The war on inclusiveness that it is waging today is part of the same murderous agenda, with its return to the colonial policy of divide and rule, and it has driven a deep divide among us. It does not recognise us as equal citizens, and by demanding that all Indians conform to its ideology, it is destroying our freedom of expression, which is our right to think, speak, write, paint, sing, dance, dress, eat, worship, and make love as we choose. By taking control of universities and all aspects of knowledge and culture, Hindutva has clamped down on the free flow of ideas, choked off discussion and debate, and outlawed opposition, all the avenues through which a society stays democratic. It has been able to spread religious and caste hatred among us by arousing the worst instincts that lie buried in many of us, and giving them free rein and official protection. This assault on our fundamental rights has come down heavily on all forms of art, as well as on Indians performing their professional duties. Writers and artists have been attacked, persecuted, and killed. Other helpless Indians have been killed by armed gangs in the prevailing paranoia that values cows above human life. As a Hindu I do not accept a situation that is distorting Hinduism for a political purpose, and as Indians we cannot watch the destruction of our modern identity which is based on respect for our diversity. Students, women’s groups, and the Dalit community have already risen against Hindutva and shown the way of political opposition to it. But as Gandhi demonstrated, this has to go side by side with looking inward at the evils in our society that make a lie of inclusiveness, because this word has no meaning if it doesn’t mean justice and equality for all Indians. It is for writers to speak through their art, through the stories they tell, to all the injustice, exclusion and cruelty that we take for granted without turning a hair, such as caste violence, religious violence, state violence, violence against women and the patriarchy that authorises and perpetuates abuses against women, and of course the inhuman mind-set so prevalent among us, even the most educated of us, that makes life hell for our fellow human beings. Such story-telling creates narratives of inclusion that confront us with ourselves, without which there can be no change in society. This is social and political activism through literature. It takes a stand. Through fiction, non-fiction and poetry it shows that this is right and that is wrong, and this is what makes it the powerful stuff of great and lasting literature. The writers we admire and recognize as great all over the world, including our own, are activists of this kind. The women writers among them have broken down age-old barriers imposing silence, by writing about the humiliations they have been subjected to. Mahashweta Devi was a leading example.

The reason why the Hindutva onslaught on diversity and dissent is so dangerous to the creative imagination is that dissent is the life-blood of art. It is the business of artists to rebel, to question the status quo, to break away from tradition, or create a new understanding of it, or show up the fallacies in it, or reject it. Art remains relevant to society only by breaking free of the rules and regulations laid down for it by what has gone before, or what the authority of the day decides it should be. Parallel cinema has gone its way and given us great cinema, and we have recently lost a great performer in Om Puri. Song and dance, painting and music, have created revolutionary new forms. An example of this in classical music is T.M. Krishna, the celebrated singer and exponent of Carnatic music who is de-Brahminising it. He says that Carnatic classical music has been taken over by Brahmin men when it was originally performed by women and non-Brahmins. He has stopped singing at the prestigious annual festival of music in Chennai, and now he organizes an annual festival at a fishing village in Chennai to bring his music to the people of the area. Dethroning Brahminism has been carried on by courageous social reformers since the 19th century, and now Krishna is doing it through music. This, as the title of this program tells us, is an example of love in the time of vitriol. And in this time of vitriol, when the heavy hand of authority hangs over art, and targets our most precious possession, which is our creative imagination, we can, through all the arts, resist being divided and demonstrate, as Gandhi did, that we are one. Writers do this by going on writing, and by dealing with all threats to freedom of expression by writing a new novel. I have nearly finished writing one myself. Inclusiveness is also strengthened by standing together in support of each other. We already have a writers’ collective under the name of Indian Writers’ Forum which is online and which highlights attacks on freedom and our resistance to them. Currently it is posting works of fiction and poetry from different languages under the heading Writers Against War. This is in response to the current hysteria being promoted by the government and the TV media inciting a belligerent nationalism. As writers we are committed to a surgical strike against war.

To end with, may I say I have reminded us of Gandhi because this is the month of his assassination by Godse in 1948, and to keep his memory alive at a time when the inclusiveness he created is in danger. I want to thank the organisers of this festival for giving us the opportunity to pay our individual tributes to inclusiveness and to reaffirm our collective commitment to this Indian reality.

More from Nayantara Sahgal on our website: “No Hindu Rashtra” (December 2016), “Writing the Age” (March 2016), “Reject Hindutva, Embrace Insaniyat” (January 2016), a statement in solidarity, and “The Unmaking of India“, a statement made by the author when she returned her Sahitya Akademi award in October 2015.

Read from the Citizens Against War series: Rabindranath Tagore, Keki Daruwalla, Arundhathi Subramaniam, Manohar Shetty, Meena Alexander, Utpal Kumar Basu, K. Satchidanandan, Tabish Khair, Sampurna Chattarji, Sridala Swami, Joy Goswami, Vivek Narayanan, Priya Sarukkai Chabria, Sahir Ludhianvi, Maaz Bin Bilal, Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee, Sobai Abdin, Anjali Purohit, Ankita Anand, Samreen Sajeda and Nilanjana Bhowmick.