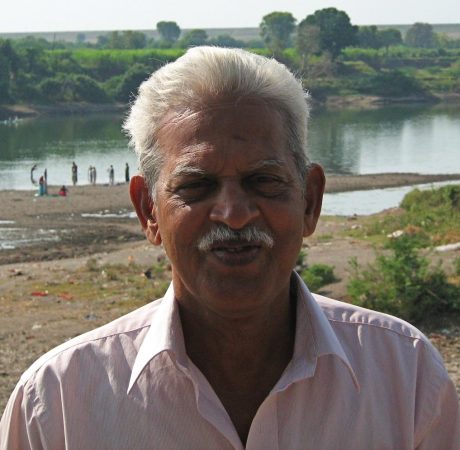

Varavara Rao is someone I have known ever since I opened my eyes to the world around me. In the 80 years of his life, he has lived around 21 years more than me. I came to know of his life in the years I missed through our conversations, family-legends, his writings and speeches. Initially, he was only an uncle who played with me; my mother’s youngest brother and just that. However, over the 50 years from then, I grew up in the kaleidoscopic shadow of his thoughts-praxis — conversations, writings, speeches, rebuttals, inspiration, rage, consolation and reconciliation.

I wouldn’t have been who I am without Varavara Rao, and it is true for the generation I come from and the one that followed. Today’s Telangana wouldn’t have been what it is without him. I have written and spoken about him and his poetry in the past, but now he is on the deathbed, in a faraway hospital, being subjected to retributive torture by the powers that be. Now, with a never-before urgency, I want to speak and write about him, through an interminable torrent of words.

Here, I will attempt to paint the 80 years of his life in seven angles — a rainbow of seven colours that characterise him — a creative writer, teacher, editor, organiser, activist, and lastly, a victim of the state, yet a humane individual.

Part I

Varavara Rao’s life as a man of letters started at a very early age. It was his family atmosphere that influenced him to begin reading by the age of 7 or 8 and encouraged him to start writing around his early teens. His first poem appeared in a Telugu magazine, Swatantra, when he was all of 17 years of age. For a respected magazine that published only one poem a week, it received due regard from poets and authors of the time. For the next 60 years, a single day wouldn’t pass without him writing and reading; no matter where he was — in a crowded home, in the hustle of his teaching vocation that wouldn’t leave him with a moment of respite, incessant traveling, in the middle of intense struggles or in the loneliness of the prison — nothing could deter him from writing and reading. The repertoire that resulted consists of a thousand pages of poetry and more pages of translations, prose, editor of about 200 issues of a prestigious literary magazine, and a vigorous researcher who found something in each of the many books he read.

Also Read: Tongues are on Trial – Brahma Prakash

Born into a middle class brahmin family in the Chinna Pendyala village of Jangaon district, present day Telangana (at the time it was part of Warangal district in the princely state of Hyderabad) in the November of 1940, he was the last of 10 siblings. Ideas of modern politics and literature flourished in his household, with four of his brothers foraying into literature. They were friends with the Kaloji brothers, Potlapalli Rama Rao, and Vattikota Alvaru Swamy, harbingers of modern literature into the early 20th century Telangana. His brothers set up libraries and publishing houses in early 1940s in their villages as well as at nearby Ghanapuram. VV’s paternal cousin was a communist and a leader of the Telangana Peasant Armed Struggle. At an early age, he witnessed him bringing in people from the “untouchable” communities of Mala and Madiga home, dining with them, and also being banished from home. Leaders of the Congress party, two of his brothers fought against the Nizam and were constant targets for the attacks of the police and Razakars. To escape the persecution, they had to flee with their families to Bezawada where they lived for a few months. All of these events had a significant impact on him from a very early age.

Also Read: Bol | Manishi Jani reads Varavara Rao

The village VV grew up in was part of the Jagir of Salarjung and had no school at that time, because of which he had to go to a private tutor. The influence of his four brothers, however, taught him more about politics and society than any formal education could have. At Hanumakonda, where he went for further schooling, his beautiful handwriting got him recruited as a copyist for a hand-scripted literary journal his brothers used to bring out, and he eventually started writing in these magazines. He came to be known as a poet in 1957, when as an undergraduate, his poem on the Soviet Union sending the dog Laika to space got published. He named the poem Socialistu Chandrudu (Socialist Moon). VV consecutively won prizes for his poetry during his Bachelor’s.

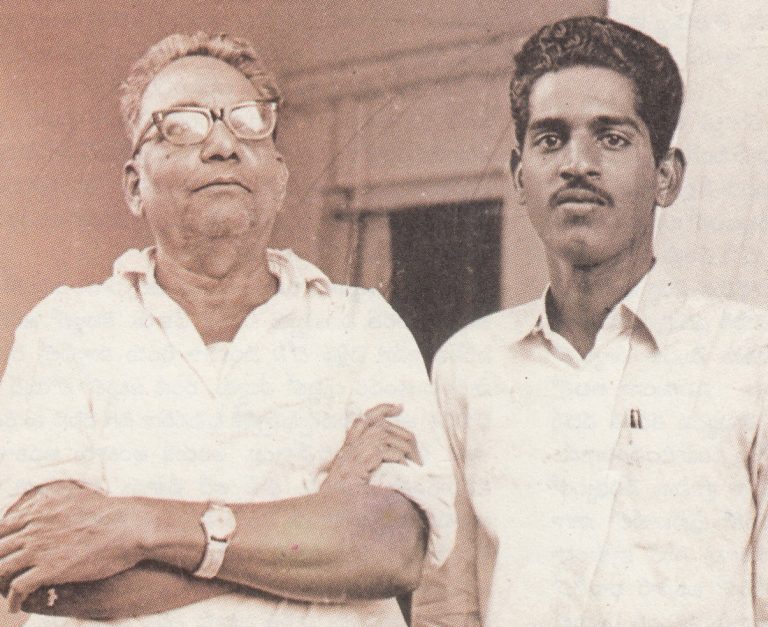

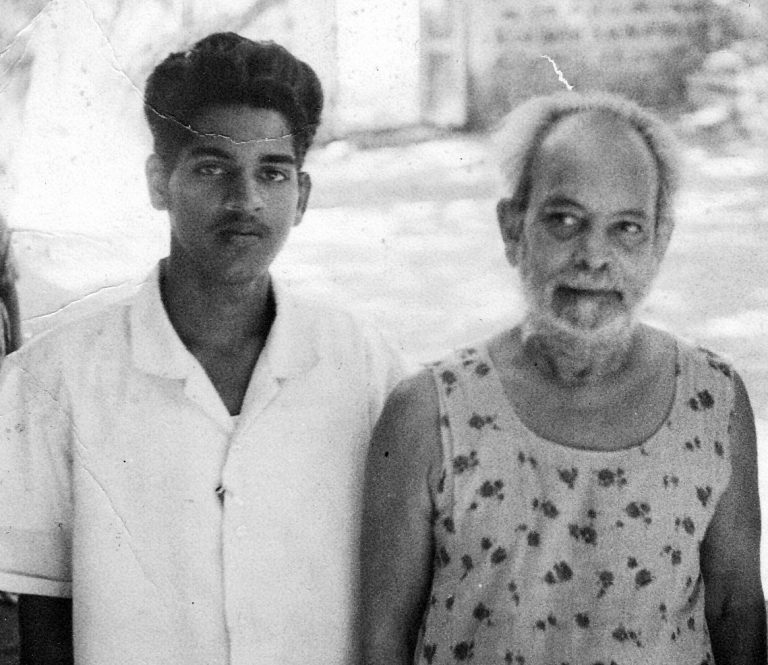

He was a Master’s student at Hyderabad’s Osmania University in 1960, when he started writing literary criticism along with poetry. His scholarship on Telugu literature during his MA was under eminent academics like Khandavalli Lakshmiranjanam, Divakarla Venkata Avadhani and Biruduraju Ramaraju. VV was also closely associated with Telugu literature stalwarts like Krishna Sastri, Kundurti, Gopichand, Buchibabu, Dasarathi and C. Narayana Reddy. He visited Chalam in Tiruvannamalai and Srirangam Srinivasa Rao (Sri Sri) in Madras and even tried to get Sri Sri to write a foreword to his book of poems written between 1957 and 1965. In 1968, he published Chalinegallu (Camp Fire), an anthology of aspirations, dreams, and a burst of emotions that characterised the youth of the post-colonial era, all marked by immense faith in Nehruvian socialist ideals and a broad democratic, progressive vision.

Having overcome the delusions of Nehruvian socialism, around 1966, he began to associate himself with the Srjana Adhunika Sahitya Vedika, a forum for modern literature that based itself on the ideals of rationalism, scientific temper and experimental fervour. It was the “Angry Sixties”, and the entire world was witnessing a wave of enraged youth protests, the Cultural Revolution in China, and the Naxalbari and Srikakulam struggles in India. All these developments fine tuned the perspective of the creative writer in Varavara Rao. The period between 1966 and 1969 saw a qualitative shift in his writing, deeply influenced by the inspirational times. Along with being instrumental in bringing together poets who stood in solidarity with the revolutionary Srikakulam movement, he also compiled an anthology of their poetry, titled Tirugabadu (Rebel), in 1969.

For the following fifty years, he committed himself to writing poetry, along with being involved in other activities. VV would publish a book of poems every four to five years and always desired to be recognised as a poet. This concern was solely based on his political conviction and it was palpable in a letter he wrote from the loneliness of the many solitary nights he spent in prison during 1985-89. In response, I wrote a poem titled Poetry Itself is Personality and ensured that it reached him in prison.

Also Read: Political Vendetta Sole Explanation for Varavara Rao’s Incarceration

VV’s poetry has been translated into almost all Indian languages. When the news of his terrible health suffused across social media last month, a solidarity movement demanding his immediate release resulted in the translation of his poetry into about 24 Indian languages and even into Italian, Spanish, Swedish, German and Irish.

Varavara Rao started writing literary criticism from the beginning of the 1960s. He also translated many poems and essays, and some of the notable ones were done in prison. In 1985-89, as an under-trial prisoner in the Secunderabad and Ramnagar Conspiracy Cases, VV kept himself busy by translating Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s The Devil on the Cross as Mattikaalla Mahaarakshasi (1992) and Detained – A Writer’s Prison Diary as Bandee (1996). Most recently at Pune’s Yerawada Jail, accused in the Bhima Koregaon case, he translated Gulzar’s Suspected Poems.

VV has always been open to learning more about the literature of any language and has perpetually been fascinated by new ideas. He reads with a craving to read more. In his seven years of imprisonment in the past and two years in the Bhima Koregaon case, he has invested all his time in reading extensively. VV has been reading hundreds of books sent to him from friends outside the prison.

During my Master’s at Osmania University around 1983, he visited Hyderabad. We went out searching for books in the city, but exhausted and hungry after a while, we thought of having some chai and biscuits. That was when we found DD Kosambi’s Culture and Civilisation in Ancient India at a shop, priced for Rs 29. Here is the interesting part — all we had was Rs 30, but he insisted on buying the book. After that, we spent the remaining one rupee on four bananas to eat. We walked to the place of a nearby friend, from whom we borrowed some money for our bus journey back to the campus.

This was around 37 years ago. Most recently, on July 15, we travelled to Mumbai after being told that he was admitted in a hospital there. After getting permission from the jail authorities, we met him at Sir JJ Hospital. Lying there all alone amid the stench of the hospital ward, he was not in a position to identify people. That was when he saw a notebook in my hand. He immediately asked, “which book have you brought?”. I replied, “it’s only a notebook”. He sighed in disappointment and enquired why I didn’t bring any other book.