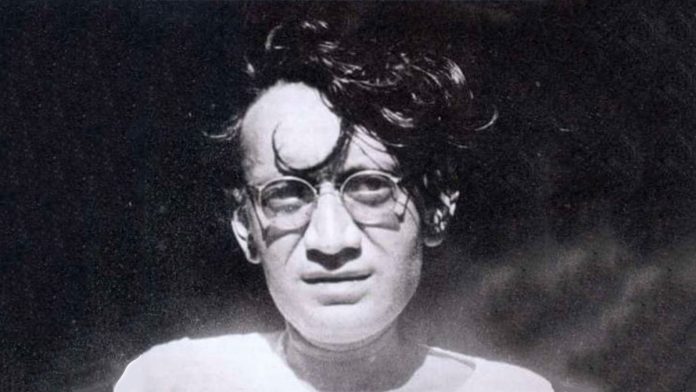

Manto. I find his stories sensational, especially the imagery and metaphors he creates out of women’s bodies. I find his language intimate and sensual. His stories create a curious rush in the reader to reach the climax where he offers a revelation that he thinks only he can. This is very apparent from the life and times of Manto. He drew his characters’ experiences from his own random observations and from his imagination, but his acquaintances, friends and interest-groups constituted elites and privileged people, upper caste writers, film makers, actors and so on. Hence there is a gap, a void, between his actual life and his characters’ experiences.

Of course, I was a naive reader when I first read Manto’s stories some seven years ago. I read him, but was far from reading between his lines. Then I read his short story, “Boo” (Odour), and it arrested me with an intimately sexual curiosity. Perhaps that is why most readers like and praise his stories.

Reading Baburao Bagul, a pioneer of modern Marathi story-writing and a dalit, drastically changed my sense of reading and understanding writers and their work. Now I cannot help but search for an element of justice, even in the literary imagination. But why justice? In the casteist and utterly unjust Indian society, if literature too serves the interests of elite castes and upper (brahmanical) classes, then it also turns into a propaganda of savarna consciousness. This, in turn, makes society more and more casteist instead of casteless.

Also read | Caste in Indian Sexuality: Reading Jayawant Hire’s Namantar

All books or stories or poems I have read have affected me, each of them differently, and this led me to the shores of a quest to find multiple meanings to life and writing. Manto’s “Boo” confuses the mind. It does not seem to know anything of the multi-layered oppression in caste society, from which writers derive ideas to build their characters. Yes, caste is a neglected theme when it comes to character-building in Manto, but there is a deeper issue: caste prevailed in India before the British came. Caste was there when the Mughals came. It was there. Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar, in his book, Pakistan, or Partition of India, says [Chapter XIII, Part IV], “But it is right to ask if the Musalmans are the only sufferers from the evils that admittedly result from the undemocratic character of Hindu society. Are not the millions of Shudras and non-Brahmins, or millions of the Untouchables, suffering the worst consequences of the undemocratic character of Hindu society?”

It is a fact that all savarna leaders and brahmin writers dwelled on a Hindu-Muslim binary, which affected the literary imagination of the time, especially in the wake of Partition. Another glaring instance is how nobody talks about the untouchables who came from Pakistan to India and were deprived of land and assistance granted to other refugees. Even Manto, then, did not attain clarity about the roots of social oppression in the very land he inhabited.

If writers only see oppression with a black-or-white lens, that of the Hindu-Muslim binary, they add to our confusion about the social history of their characters. We start perceiving society from the lens of these writers, looking out from which we forget that there exist multiple peoples who are being erased, deformed, and made agency-less.

Manto is known to have sympathy for “lower” caste characters in his stories. This is evident in his stories and how he locates his characters, as well as from his anxiety to associate “tragedy” with them. I, too, thought that his sympathy would be meaningful when I first encountered his stories. Had I not read dalit theory and literature seriously, I would always have been an admirer of his work. But today I find Manto’s sympathy useless: it comes from an ignorance of the social reality of caste. Sympathy which derives from ignorance is as dangerous as violence.

It is also a fact that in the past we lacked the perspective to locate Manto’s stories. Now that we do, and his works can be better understood, his lack of understanding of the roots of social oppression in India are evident—and this lack is far more pronounced in Boo.

Manto’s “Boo” satisfies savarna guilt. And it violates a woman’s sense of dignity. Manto’s “Boo” erases women’s agency, replaces it with the adventure of a privileged man. This is evident in its depiction of the quest of a savarna male character for sexual congruence with a supposedly lower caste woman, who, reduced to an object, remains nameless in the story.

“She” is the most explicit term used when referring to the female character in “Boo”. While “She” is objectively described as a sweatshop worker, Randhir, the central male character, is described with great indulgence. His portrayal offers overt clues into his social and cultural background:

“Randhir felt bored and little sorry for himself. His ego hurt because he was far more cultured, far better educated and much better looking than those British tommies who were welcome in these clubs while he wasn’t because of his colour.1

So cultured, educated, better looking Randhir feels oppressed in the presence of the British. But then in whose comparison is he all these other things—more cultured, educated and better looking?

Also read | Dalit Literature: On Memory or Death

Manto’s descriptions clearly indicate that he belongs to a savarna-feudal background, for the word that best describes him is womaniser. But right now, he is hurt. And an injured savarna man’s hurt pride must be consolidated. This man, with all the privileges of a savarna, but subjugated as an Indian in British India, wants to revolt. Yet he lacks clarity as to the real source of oppression in his society: caste, which has now engulfed other religions in India, such as Islam and Christianity.

Randhir’s experiences clearly show that he is seen as inferior by the British. But his instinct tells him that he is an unquestionably superior being as per the Indian caste order. That is why he has easy access to a working-class low caste woman, as if she were a legal entitlement bestowed on him by society. The story mentions that Randhir wants her—“She”—as his revenge. He sees “She”—her—standing under a tamarind tree, protecting herself from the rain. He signals to catch her attention then gestures her over to his house upstairs.

What allows Randhir to approach a strange woman who is simply standing in the rain? It is his savarna instinct about women, codified and justified by the Manusmirti. For centuries this code has justified a savarna man’s desire for “lower” caste women, without a care for their consent and it has developed into an instinctive form of social behaviour. Manto’s Randhir is no exception. In his case too, consent is replaced with a “mystic leap” in which, without consent or communication with the woman, an act desired by a savarna man takes place. So “She” comes upstairs. Then Randhir says, “Take your wet clothes off unless you want to catch something.”2

It is Randhir who now sees in her eyes an inkling and understanding of why she has been asked upstairs. “She” gets no dialogue, absolutely no agency. Randhir just sees the consent in her eyes that he wants to see. Even her gaze is made invisible just as her voice is silenced. They sleep together.

While she is described only as a body, an object through which he finds fulfilment for his desires, he is portrayed as a person with a past, one who belongs to a culture and who has a certain acceptance among women, despite being a womaniser. Well, you can break moral codes of caste society if you are savarna and still remain unquestioned and accepted in society.

“Randhir was no novice to such encounters. He had slept with scores of girls and he knew the ecstasy of fulfilled women, his hard chest pressed against their tender breasts. He had known women who had no experience of men and who told him things one doesn’t tell strangers3

It is caste privilege which makes Randhir acceptable, because an act for which a dalit man would be despised and made to feel morally guilty is accepted when Randhir does it.

But “She” is still different. She is dark and her body emits odour. Randhir is aware of it. Her darkness attracts him, her odour enchants him, engulfs him with a sense of fulfilment—not her being, not her thoughts or her words.

To understand “Boo” fully is to know that Manto is impulsive, if not insidious as a writer. Because his sympathy for the “invisible people” of society does not offer any indications about the history of “She”. All she is is a worker in a sweatshop, nothing more. Why is it that her odour fulfils him, a savarna privileged man? Why are not her thoughts, her ideas about life, her words, her feelings, her emotions attractive to him? Why does Randhir only dwell on her odour, which he finds both pleasant and unpleasant, and the colour of her skin?

Clearly Randhir is a guilty savarna man. He is guilty because what he desires is socially not acceptable and what he does not desire is readily available, by virtue of his caste and privileges. “Boo” is what he wants but what he has to live with is artificial fragrance, so as to maintain caste.

Also read | Ambedkar: A Spartan Warrior who Made Knowledge and Justice his Weapon

His savarna guilt is consolidated by Manto’s sensational and sexist depiction of “She” as a human object who emits an odour which is alien to him: the odour of labour and dignity. As we are clearly told:

Randhir had always hated the smell of perspiration and after a shower he would rub his body with talcum powder and put deodorant in his armpits. But wasn’t it strange that he kissed her repeatedly in her armpits and felt no nausea? In fact, a deep sense of satisfaction had washed over him.4

The nausea which he does not feel is an indicator of his temporary wokeness from his caste privileges so that he could feel liberated. Because in sexual acts, saliva, sweat and smells, which are otherwise not a facet of attractiveness, become sensual elements too. Randhir is a typical guilty savarna man who craves for something he does not have and cannot own and a coward who rejects it anyway, after consuming it transitorily. That is why, although “She” fulfils him, yet he marries a privileged girl (of his caste), the daughter of a judge.

It may appear that Randhir has no agency vis-a-vis White women, and so deliberately acts out the inverse with “She”, by snatching the agency of a working class lower caste woman. But in fact Randhir has agency. He is feeling, he is expressing, and he is proud of who he is—he even compares himself with the British.

Randhir is pathological. Even after marriage he cannot get over the odour of “She”, which essentially “penetrated his body like an arrow”. He is hurt even now, but in a different way—sadistically. His social interests do not allow him to have “She”, but his hurt-consciousness requires her. He turns into a museum of the savarna-male complex. On his wedding night, sleeping with his wife, “Randhir ran his hands over her white body but felt nothing. There was no sense of gathering excitement under his skin.” He seeks that “lost, remembered” odour in his wife’s perfumed body.

Randhir is confused and unsatisfied throughout the story. It is for two reasons. He is incapable of breaking social norms and does not know that he is suffering from a guilt complex. He jumps from one woman to another, to eventually marry a “girl” from as privileged a background as he. “Boo” represents the image of a guilty savarna man who is unable to liberate himself. It portrays women as objects through which a savarna man seeks liberation but remains incapable of introspection and accepting his own guilt and patriarchy.

In “Boo”, the body of a woman is subjugated to generate sexual sensations among readers and not sensitivity. This is because her thoughts, her struggles, her words, her ideas are completely absent. Woman is an object in Manto’s “Boo”. That is why it is pleasing to the senses but devastating to our consciousness.

Notes:

1 Saadat Hasan Manto, Kingdom’s End : Selected Stories, Penguin Random House, 2007.

2 Id.

3 Id.

4 Id.