Fanon has narrated the stream of thoughts of a youth living under colonial suppression; a repulsive situation for the oppressed. When the colonisation operates via “public law”, to use Ambedkar’s term, rather than via legal precepts, it makes oppression a subtle practice in which neither body nor mind is free to act as per will. The will is morphed, mutilated and replaced by the codes of conduct of the colonial ruler. Yet, this is not the worst. The worst befalls the oppressed when he finds “the order of the world” has been colonised. Brahmanism, in this sense, is much a subtler form of slavery; one that is far from being apparent. It can only be understood by decoding the “emotional” world of an oppressed. The emotional world of characters in Baburao Bagul’s stories is so rich with these “emotional codes” that by deciphering them we can almost see the blueprint of revolt against caste society.

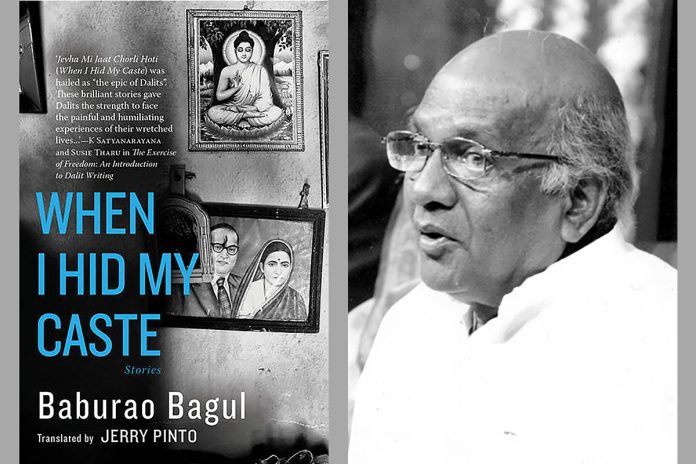

In 1963—just seven years after a “new man” born out of the conversion to Buddhism of Babasaheb Ambedar acquired a historical sense of “spiritual democracy” (to use Kancha Illiah Shepherd’s term) and an instinct for social equality—Bagul published his first short story collection, Jevha Mi Jaat Chorali in Marathi, now translated into English as When I Hid My Caste. It stirred up the Marathi literary world, especially Brahmin writers, with unbearable madness. One prominent reason, among many others, was his depiction in these stories of the emotional world of a dalit. The portrayal was woven with a clear sense of the pain he experienced and the vision to free him from it.

Of the book’s ten stories, “Revolt” demands special reading. This is because it features the past, the present and the future, creating a timeless narrative of a dalit who had newly-absorbed the taste of transiting from one world to another, from being oppressed to feeling assertive, powerful and the creator of his own life of the mind.

Also read | Fanonian Reading of Daya Pawar’s Baluta

Revolt is a story of the rebellion of Jai, son of a bhangi father, who worked as a bhangi, was called “bhangi”, and lived as a “bhangi”. It is the story of a dalit man who comes in contact with books, words, and the emotional turbulence that then occurs in his subconscious world. Books offer him a future in which he is free, but his father represents the deprived past from which it is difficult for him to escape. All this takes place in Jai’s present.

Jai’s parents married him off very young; even before he hit puberty. While studying for his matriculation, he hardly looks at his wife. He is yet to develop romantic feelings or sexual attraction for her. The reason is the emotional turbulence within him, due to his anxiety to break away from the past to which he is being made to belong—the past of being bhangi, the son of “bhangi”. He finds the objective conditions around him, of poverty, filth, and stigma, disgusting—unlike the books he reads, which show him a bright future. It is here that he becomes an emotionally violent man. As Bagul says, he becomes “a man who could snarl at his father like an animal when the latter lay on his deathbed; a man who could ignore the poverty and deprivation in his own life; a man, who though physically male, would not so much as look at his own wife.’1

Yes, Jai sees himself and his wife as victims of conditions that are essentially constructed by caste. He is as powerless as his wife, but he has books—his wife does not. Hence, he is closer to discovering the “reality”. Fanon says: ‘The native discovers reality and transforms it into the pattern of his customs, into the practice of violence and into his plan for freedom.’2

But the practice of violence here is not on the outside or with other humans. It is primarily against the “regressive thinking” that a person is made to internalise by the caste system. Jai is violent against himself. And this is very apparent. As Bagul writes: “Over the past few years, Jai, though he had lived in the same house, had grown aloof and isolated; so now he simply let his head rest on his father’s chest and allowed himself to enjoy the feeling of being loved”.3

This emotional violence leads him to an isolation from his past, but he starts feeling disgusted by this, too, as it forces him to be a part of his past again, like his father did. In this sense, he did not hate his father, nor had he isolated himself from him. He hates that his father was a victim of caste and was unable to resist it. Interestingly, Jai is also aware of his own isolation. He cannot bear to remain aloof from the feeling of being loved—the feelings he had experienced when he had laid his head against his father’s chest. It is this unique emotional condition that is a product of the caste system. Neither can Jai fully embrace his past nor can he afford to totally isolate himself from it. This is the caste-complex of the victims of the caste system. Fanon explains:

“The problem of colonization, therefore, comprises not only the intersection of historical and objective conditions but also man’s attitude towards these conditions.”4

Also read | From Mahars to Buddhists: The Culture of Protest

Here, born in the family of a bhangi, an inhumane profession justified by caste (and by Mahatma Gandhi), Jai could not help but hate even his own mother, when he saw her stigmatised for being “bhangi”. He vehemently opposes his parents, who pursue him to follow their work due to their poverty.

However, in brahminisation—which is much more horrendous than colonisation—when Jai is persuaded to work as a “bhangi” for the sake of his poverty-stricken family, his attitude does not only turn violent. He also interrogates the entire system which is primarily responsible for making him a man who is not free to pursue his aspiration to follow a life of the mind; to acquire a PhD.

Jai vents: “What kind of culture is this? Where a man can treat the mother who gave him life with contempt simply because she does the work of a bhangi? Where he can insult her and refuse to eat the food she cooks? If this culture had not created untouchability, I would not be the chief tormentor of my poor aged mother…” 5

Jai realises his own victimisation the moment he poses these questions. This is a revealing moment, because after this realisation his emotions for his parents turn mature. Now, he can see beyond himself and his dreams. But he also knows that doing the work of a bhangi will never free him as a man. Jai develops the ability to sacrifice—but does it come at the cost of his freedom? Yes.

He now consents to do the work of his father: cleaning toilets, sweeping roads and disposing of human excreta in a tin pot. On his first day at work, his supervisor mockingly bypasses his educational background and calls him “bhangi”. He swallows the poison of humiliation. He is ordered to lift human excreta in a tin pot. The mere sight repulses him. Yet the unimagined happens. He now has a tin pot on his head, full of human shit. He is asked to hurry up.

Bagul writes: This blind hurry meant the tin shook and spilled. The contents spilled over, glug, glug, on to him. And just as a man who finds that a snake has coiled itself around him and has bitten him lets loose a scream of agony, Jai screamed, “Aai”.6

While he was carrying the filth, his attention is snatched by his mother, who had fallen ill. He shouts and runs towards her, with a spillage of excreta running across his body, its smell making him feel disgusted about life. He reaches her, but she insists that he should grab the tin pot he had thrown, for she wants him to work properly on his first day. But he could not. The carter, who is in charge of making him work, shouts at him, orders him to stay away from his mother, lift the tin pot and dispose of the excreta.

His disgust causes the revolt, the hatred, the horror that was running through Jai’s nerves to rise within him. So he took the tin, threw it where it would go, and then grabbed the carter with both hands.7

Also read | Dalit Women as Active Participants in Ambedkarite Movement

In this fight, Jai beats the carter to death. A person who dreamed of becoming a professor becomes a murderer instead. But he is fully aware of his rage, his anger, and what he has done. He reaches his mother and begs for punishment from her. He seeks justice from his mother. Because Jai, who has risked his dream to become a “bhangi”, is now free, even as a murderer.

The path to his freedom passed through violence. He is de-brahmanised now. Because, as Fanon says, “the extraordinary importance of this change is that it is willed, called for, demanded. The need for this change exists in its crude state, impetuous and compelling, in the consciousness and in the lives of the men and women who are colonised…their first encounter was marked by violence…”8

Fanon provides one more dimension of violence by the one who is colonised when he says, “A normal black child, having grown up with a normal family, will become abnormal at the slightest contact with the white world.”9 In Jai’s case, we find that the violence was not willed, but was a demand created by the brahmanical code of conduct between humans, of seeing someone as perennially inferior and filthy. The freedom which Jai sought once through books, was hardly conceivable without violence in the situation that he was pushed into.

Notes:

1 Baburao Bagul, When I Hid My Caste, Speaking Tiger, 2018

2 Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, Penguin Classics, 2001

3 Baburao Bagul, When I Hid My Caste, Speaking Tiger, 2018

4 Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, While Masks, 2008, Grove Press

5 Baburao Bagul, When I Hid My Caste, Speaking Tiger, 2018

6 Id.

7 Id.

8 Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, Penguin Classics, 2001