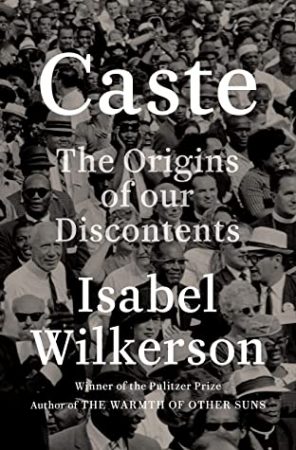

In its 1 July issue, The New York Times Magazine published an eye-catching feature on America’s Enduring Caste System by the Pulitzer-winning writer Isabel Wilkerson. The feature is adapted from her new book, Caste: The Lies That Divide Us. For an Indian, who is raised in a caste from the moment of his birth and eventually dies in it, this feature is very striking, for in India—the land of birth of the unnatural caste system—the public imagination rarely associates America with caste.

For westerners the caste system is an integral part of Indian culture; some also see it as a divisive mechanism. But very rarely is caste perceived as the cruel imposition on human desires, aspiration, feelings and dreams it is. It seems impossible that one who has never lived in India could capture the gravity of the assault of caste so well as Wilkerson. To analyse the caste system is one thing; but analysing it after being assaulted by it is completely different. If you are a victim of caste, your analysis would recommend its complete annihilation and nothing else, nothing less.

For someone who is not part of caste society—never at its receiving end—to have captured its meaning is a sign that serious engagement with caste at the global level has arrived. Wilkerson’s article is fresh in outlook and original in the position from which it attempts to look at caste: as a notion that has for long governed the minds of Americans as well. Wilkerson succeeds in capturing the subtle differences between race and caste: one can hide caste but not race. For her, caste is many things, all of which she makes clear through her convincing use of a range of metaphors. Hers is a rare literary achievement, one no Indian savarna writer has managed so far. She describes caste as an old house which is exceedingly dangerous for those who live in it.

Also Read | Dalit Literature: On Memory or Death

Citing the workings of caste as the notion that propelled the killing of George Floyd, she says, “What we did not see, not immediately anyway, was the invisible scaffolding, a caste system with ancient rules and assumptions that made such a horror possible, that held each actor in that scene in its grip… Like other old houses, America has an unseen skeleton: its caste system, which is as central to its operation as are the studs and joists that we cannot see in the physical buildings we call home. Caste is the infrastructure of our divisions. It is the architecture of human hierarchy, the subconscious code of instructions for maintaining, in our case, a 400-year-old social order. Looking at caste is like holding the country’s X-ray up to the light.”

This is intriguing, isn’t it? No Indian savarna writer, who owns caste privileges and claims to be anti-caste, progressive or liberal, has ever reached such an honest metaphoric level of decoding caste and understanding its subtleties. Wilkerson is conscious of the origin of this subconscious code which guides our behaviour. She imaginatively interprets this code when she says, “A caste system endures because it is often justified as divine will, originating from sacred text or the presumed laws of nature, reinforced throughout the culture and passed down through the generations.” Yes: caste is inheritance. Like parents bequeath bones, flesh and blood to their children, they also bequeath their caste, subconsciously, sometimes unknowingly.

Wilkerson falters when she says, “The hierarchy of caste is not about feelings or morality. It is about power—which groups have it and which do not.” It is true that caste is about power. But it is not only about power. Some castes are power, others are powerless. Can we say that a dalit IAS officer, despite having power, feels free to use that power in the same way a brahmin IAS officer would, considering their social capital? Or would a dalit IAS officer be treated the same way by their savarna colleagues? To cite an example from the past, when Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar, the most highly-educated man in India in his time, went to Baroda to work as Military Secretary for the Maharaja of Baroda, he was treated harshly since he was born into an untouchable caste. Can we say that when the identity of a dalit who has acquired power is revealed they will be treated in accordance with their power, or will their caste status dictate how they are treated? There are thousands upon thousands of cases which prove that caste is more than power.

Some castes are always moral, some are always immoral. To see it phenomenologically, some castes are transformed into feelings of being rightand auspicious and some into feelings of being wrong and inauspicious. A material dialectics is at work here and Wilkerson seems to have overlooked it. Nevertheless, her arguments and explorations are impressive. They take us to a whole new level of seeing caste. She says, “Race does the heavy lifting for a caste system that demands a means of human division. If we have been trained to see humans in the language of race, then caste is the underlying grammar that we encode as children, as when learning our mother tongue. Caste, like grammar, becomes an invisible guide not only of how we speak but also of how we process information, the automatic calculations that figure into a sentence without our having to think about it.”

Also read | Baldwin and I: Beyond Race and Caste

To sense the urgent need for annihilating caste, what we have always needed is a metaphorically intense explanation such as this, and not lethargic academic arguments. Caste is explained to us in India by dalit writers in a much more intense and profound sense, yet, it is caste that has prohibited Indians from taking cognisance of the urgency to kill the monster of caste within us. Wilkerson’s daring narratives on caste, which sees it primarily as a psyche behind oppression, raises the seriousness of this issue exponentially. This is promising because it makes us see caste as it exists beyond the Indian subcontinent or among the Indian diaspora. She makes caste a psychological issue that haunts the world, without the world being aware of it.

Wilkerson says, “Caste and race are neither synonymous nor mutually exclusive. They can and do coexist in the same culture and serve to reinforce each other. Race, in the United States, is the visible agent of the unseen force of caste. Caste is the bones, race the skin.”

If we seek an honest answer to whether racism is as rampant as casteism in India, then Wilkerson convinces us that it undoubtedly is. In India, a dark-skinned person is assumed to belong to a low caste or as a dalit. This is because a lie—that a fair-skinned person is an upper caste person—governs our consciousness. This lie, in the last five decades or so, has been consolidated by Bollywood movies. Racist behaviour has governed the minds of savarna Indians for long and they, while capturing the means to define culture and control politics, after gaining undisputed dominance over the culture industry, have consolidated outrightly racist and casteist behaviour as the acceptable norm.

Wilkerson’s long and gripping article exhibits an understanding of caste unlike even the savarna scholars and writers who are settled outside India. She surpasses them all, not only in understanding caste, but in bringing our attention to the need for its annihilation in order to create a just and beautiful world. This profound narrative of responsibility, from a black woman who has faced discrimination in America, makes it not that surprising. There is no doubt that her book will foster a serious and intellectually and emotionally vibrant engagement with the anti-caste movement.