Image Courtesy: MakeUseOf

Image Courtesy: MakeUseOf

“In a country where the need is to deal with sexual violence, they’re prosecuting writers”

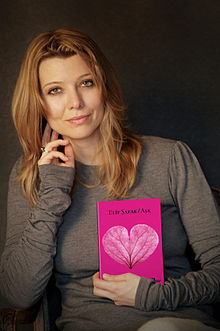

In May 2019, The Guardian reported that Elif Shafak, Abdullah Şevki and a few other writers of fiction, were being investigated by Turkish prosecutors for writing on subjects like sexual assault and child abuse.

The investigations were launched after a page from a novel by Abdullah Şevki triggered a vindictive debate on Twitter, accusing the writer of condoning child abuse. The passage featured a first-person account of sexual assault on a child from the eyes of a paedophile.

Turkey’s bar association had also filed a complaint demanding the government to ban the book and charge its author and publisher with “child abuse and inciting criminal acts”. Subsequently, the Turkish ministry of culture and tourism said it had filed a criminal complaint against the writer.

Soon after, passages from novels by other writers including Shafak and Ayşe Kulin were shared on social media, making similar accusations. Following this, Shafak told The Guardian that she had received thousands of abusive messages and that a prosecutor has asked to examine her novels – in particular, The Gaze (1999) and Three Daughters of Eve (2016).

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

“They want to investige anything that has any passage on sexual abuse of children in Turkish literature,” Shafak said. “This is a very new focus for them. And of course, the irony is that this is a country in which we have an escalating number of cases of sexual violence against both women and children. Turkish courts are not taking action, the laws have not been changed. So, in a country where they need to take urgent action to deal with sexual violence, they’re instead prosecuting writers. It’s the biggest tragedy. It has become like a witch-hunt,” reported The Guardian.

This is not the first time that Shafak has been caught up in a case against the state. In 2006, Shafak was tried and acquitted for “insulting Turkishness” after referring to the massacre of Armenians in the first world war as genocide in her novel The Bastard of Istanbul.

On 31 May 2019, speaking at the Hay Festival, Shafak urged the international community to show support for the country’s authors, journalists and academics and warned that all traces of democracy were being crushed there.

Elif Shafak is an award-winning novelist, teacher and a political scientist. She has published 17 books, 11 of which are novels. Her books have been translated into 49 languages and she has been awarded the prestigious Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. She is an activist on women’s rights, minority rights and freedom of speech and regularly writes and speaks about these issues.

Thus, the state’s crackdown on journalists and writers like her is not just an attack on freedom of speech but an act of witch-hunting.

In an op-ed written for The Guardian in April 2019, Shafak made a crucial point about literature in our contemporary times. “To understand the far right, look to their bookshelves,” she wrote, indicating how publishing trends have enabled ideas which were once on the fringes to become part of the mainstream.

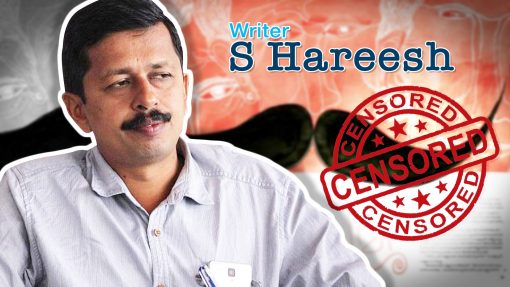

Similar instances of censoring and intimidating artists have been happening in India with the advent of the far-right at the centre. Last year in July, Malayalam writer S Hareesh, winner of the Kerala Sahitya Akademi award for short fiction was forced to withdraw his first novel Meesa (Moustache) following attacks from right-wing groups in Kerala.

Hareesh was accused of “hurting religious sentiments” and “maligning Hindus” after the first three chapters of this novel were published serially by Mathrubhumi weekly.

Hareesh was attacked for a reference one of the characters in the novel makes on women’s visits to the temple. Extracts from the weekly were shared on social media, resulting in widespread criticism by Hindu organisations such as the Yogakshema Sabha, BJP and others.

The writer was threatened that his hand would be chopped off to “teach him a lesson”. Copies of the weekly were burnt and members of his family were viciously trolled. As a result, he withdrew his book and decided to publish it when “the climate is congenial”.

Writers from across languages including Volga, Adil Jussawalla, and K Satchidanandan came out in support of S Hareesh. Poet and translator Vivek Narayanan said that these threats are no longer an aberration to the rule, but the rule itself. “It is shocking to find that such vicious, horrific threats have now become a regular, everyday go-to tactic. These are not “Hindus defending their religion”— no, they are a gang of criminals, terrorists, manufacturers of outrage, opportunists looking for a fight and, indeed, also insecure cowards who care little and know little about the texts they purport to defend. These are the enemies of honest art and literature, of vigorous argument, of discussion, and finally, of thought itself.”

A plea to ban the book was made to the Supreme Court of India by N Radhakrishnan, a resident of Delhi. However, The Chief Justice of India, Dipak Misra, refused to ban the novel and observed that “the culture of banning books directly impacts the flow of ideas”. Writers welcomed the Chief Justice’s observation and called it “not just a victory over a case of a writer, but a victory for the rationalists, journalists and intellectuals like Dabholkar, Kalburgi, Pansare and Gauri Lankesh, and the values they stood for. They were murdered by the right-wing fundamentalist group because they wanted to curb their freedom of expression.” Meesha was later published by DC Books in 2018.

Read More:

Sudha Ragunathan Faces Social Media Storm over Daughter’s Engagement to African American Man

Academics and Writers Respond to the UP Private Universities Ordinance