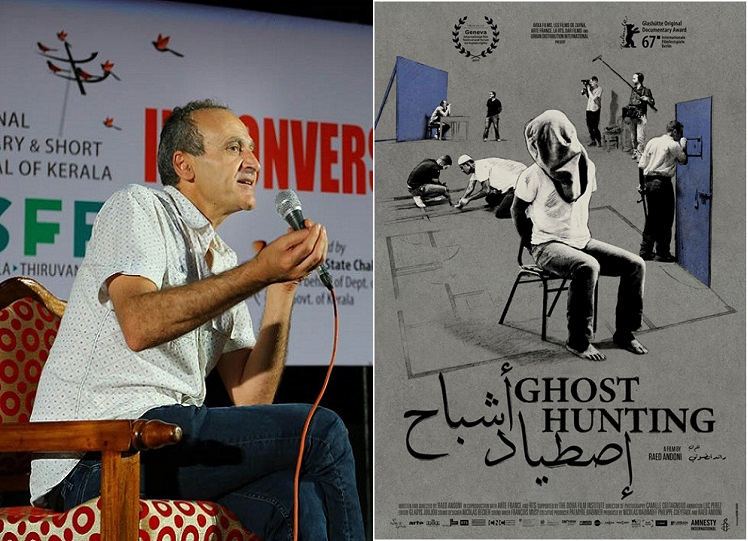

We are nearing the end of the hectic five days of the International Documentary and Short Film Festival in Kerala (IDSFFK), held in July 2018. During the on-stage conversation, Palestinian filmmaker Raed Andoni says his latest film, Ghost Hunting, is a homecoming of sorts. Andoni has been living in France for the past ten years. He was in India as the Chair of Jury for the documentary section at the IDSFFK, and also traveled to Mumbai for a screening of Ghost Hunting. The screenings and discussions were also an effort to build ties of solidarity with Palestine. Andoni, like many artists from Palestine and those supporting the Palestinian freedom struggle, supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement. His brief stay in India allowed several opportunities to understand the terrains of arts and politics as they engage with each other in the context of the Palestinian struggle.

A day before this conversation, we had the opportunity to watch the film with him. I was still reeling under its intensity when Andoni told me that his previous film, Fix ME (2009), engages with the subjectivity of the ‘self’ in a collective. This collective for him is his family and social life in occupied Palestine. For a society struggling for its freedom and under constant siege, the collective is the strength as well as the refuge. Inspite of this, Andoni said he struggles to place his art and himself, and its individual nature, in this collective. His latest film, by the way, delves into precisely this collective strength.

Ghost Hunting is part-fiction, part-documentary where ex-prisoners recreate the notorious Israeli interrogation centre, Moscobiya (in Jerusalem), and take up roles as prisoners and interrogators. Andoni was himself imprisoned in the same centre in the film. He films the process of recreating this centre in a basement in Ramallah, occupied West Bank. This is interspersed with fictional role playing by ex-prisoners. While the recreation of the interrogation centre sends chills down the spine, the personal stories of the characters and their inter-personal relationships deeply engages the viewer. It seems that the process of making this film is also a collective catharsis of ‘ghosts’ each of them has buried within themselves.

As an Indian, watching this film with others who may or may not know the Palestinian context too well, I wonder if the viewers at IDFSSK could connect to the film. This eventually made me wonder of a larger question: what is the role of a work of art, such as a film, in the everyday practice of politics. Surely the importance of informative documentaries has its place in political work. But where would one place a film like Ghost Hunting, which takes us to the internal struggles of people living under occupation, but who are also average people with egos, guilts, jokes and an unending need for coffee and cigarettes? The discussions after the film, however, clarified some of my doubts. The audience was deeply inquisitive about the characters, their lives, the various details of the process of filmmaking, and finally the indomitable spirit of the people they just saw on screen. I was, perhaps, asking the wrong question.

Israel’s military occupation does not ever appear in the film in its physical form, and yet it is present everywhere. I could relate this formal characteristic to Andoni’s remark in one of his interviews: Israel also occupies the mind. Liberating the mind from this fear is a precondition for the freedom struggle. Quite importantly, none of his characters see themselves as victims, and they chart their own journeys through the course of the film and engage with the trauma of prison, torture and interrogation. One of the character’s son, a boy of 3-4 years, thinks of every Israeli military building as the place where his father was imprisoned. Given that we are talking about occupied West Bank which has several illegal Israeli military structures, for this boy, his father was imprisoned in hundreds of buildings. At the end of the production of the film, the set is turned into an art installation and the characters bring their families over. The boy finally has an answer to where his father was imprisoned. He plays there with his friends and the place does not appear nightmarish in his imagination anymore. It was impossible to not connect to that sense of a private, yet significant, victory.

Read more:

Notes from discussion: Police Subjectivity in Kashmir by Gowhar Fazili

Seeking Palestine: New Palestinian Writing on Exile and Home

Why Asking Bands to Not Perform in Israel is Not an Attack on Freedom of Speech and Expression