No, painting is not made to decorate apartments. It’s an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy.

– Pablo Picasso

There is a saying in the Marathi language: “बामणा घरी लिहिणं, कुणब्या घरी दाणं आणि मांगा-महारा घरी गाणं.” A Brahmin’s house has the alphabet, a Kunbi’s house has grains, and Mang-Mahar homes have music. In the traditional village set-up, the Mang community played halgi , the Gondhali played sambal , Dhangars were masters of dhol , and Mahars played ektari . The culture of knowledge, farming, art and music was segregated by caste. Moreover, for many of the castes deemed ‘untouchable’, singing and performing music were vital means of sustenance. Facing oppression and discrimination for centuries, Dalits have preserved their history, bravery, pain, happiness and philosophy in the form of jatyavarchi ovi (grindmill songs or poems), oral stories, songs and folk music. Before Dr. Ambedkar’s rise to prominence on the national stage, the Mahar people played ektari to Kabir’s dohas , and sang bhakti songs for Vitthal and bhajans worshipping god.

When Dr. Ambedkar emerged on the horizon of Dalit politics, after 1920, these art forms and their artistes played an important role in publicising and disseminating the movement for enlightenment he had launched. They explained the social changes fostered by Dr. Ambedkar’s movement, everyday events, and Dr. Ambedkar’s role, his message, life and struggles – all in such language that the unlettered and uninformed could understand. Once, when Dr. Ambedkar watched Bhimrao Kardak and his troupe perform a jalsa (cultural protest through songs) at the Welfare Ground in Mumbai’s Naigaon area, he said: “Ten of my meetings and gatherings are equal to a single jalsa of Kardak and his troupe.”

Performing in the presence of Dr. Ambedkar, Shahir Bhegde had said:

महाराचा पोरगा बिट्या लई हुशार

बिट्या लई हुशार

साऱ्या जगात नाही असं होणार

अंधारात आम्हास्नी वाट दाखविली

भोळी जनता त्याने जागृत केली

The young Mahar boy [Ambedkar] was very clever

Indeed, very clever

This wouldn’t happen in the whole world

He showed us the way out of the darkness

He awakened the innocent

Dr. Ambedkar’s movement brought a wave of awakening among the Dalits. Jalsa was the instrument of this movement, and shahiri (performance poetry) the medium – and thousands of known and unknown artistes.

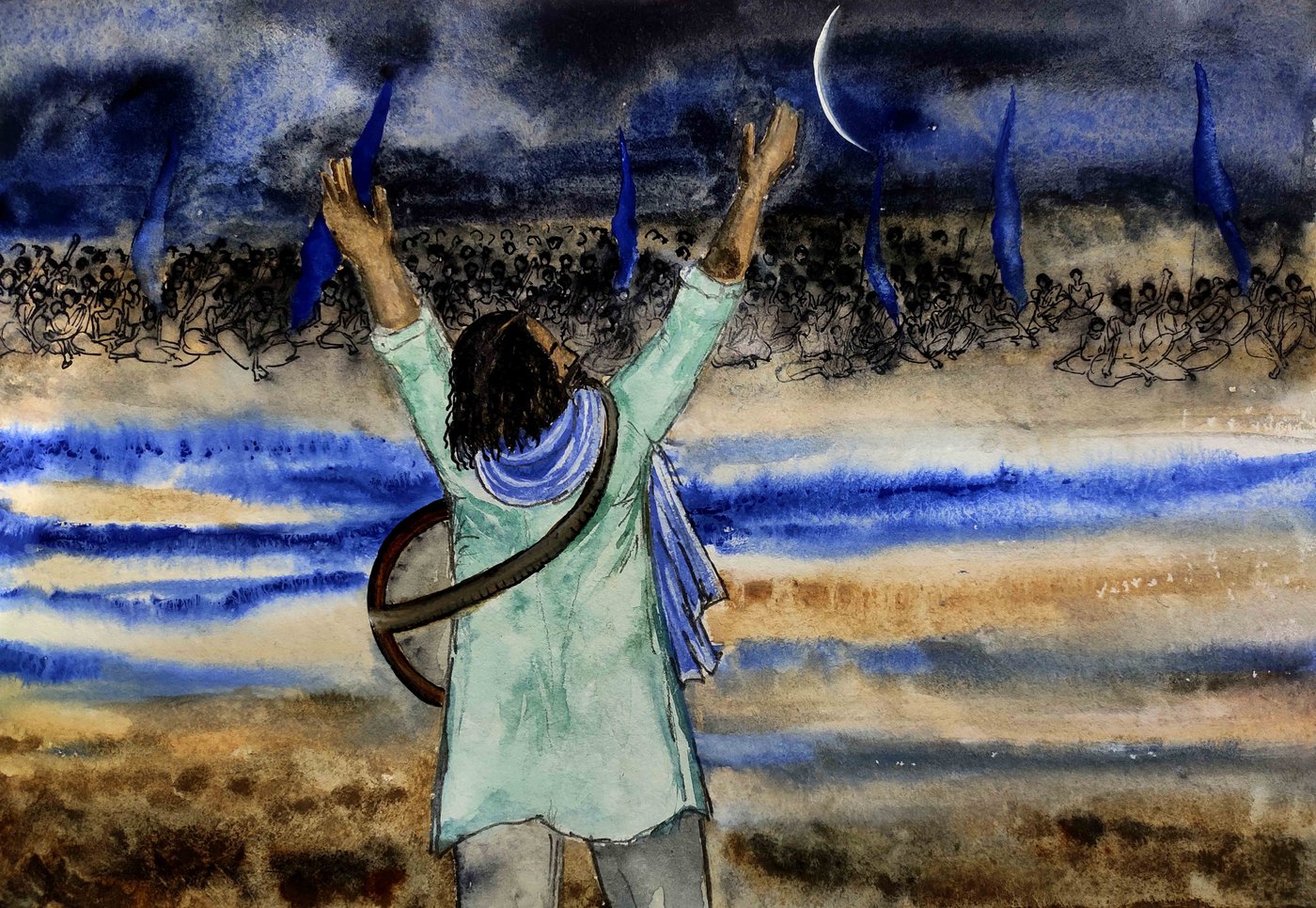

As the Ambedkarite movement reached the villages, a typical scene would be visible in Dalit vastis (settlements) – half of them had tin roofs and half had thatched roofs. There would be a platform at the centre of the vasti , where a blue flag would be hoisted. And under the blue flag, children, women, men, and the elderly would gather. Meetings were held, and in these meetings, Buddha-Bhim geet (songs) were sung. Books of songs by small and big poets were brought from Chaityabhoomi (in Mumbai), Deekshabhoomi (in Nagpur) and other big cities. Though the women and men in the Dalit vastis were unlettered, they would ask school-going children to read out the songs, and memorise them to sing them later. Or they would memorise a song performed by a shahir and perform it in their vasti . Some women farm labourers returning after a long, tiring day, would start by saying, “ Bhim raja ki jay! Buddha Bhagwan ki jay! ” and then sing – and transform the mood in the vasti into a happy, upbeat and hopeful one. These songs were the only university for Dalits in the villages. It was through them that the next generation encountered Buddha and Ambedkar. In the rough and ready language of these singers and shahirs , the younger generation imbibed the powerful songs about Buddha, Phule and Ambedkar in their psyche – from where it was impossible to ever forget. The shahirs shaped the social and cultural consciousness of an entire generation. Atmaram Salve was one such shahir , who was instrumental in moulding the sociocultural awakening of Marathwada.

Born on June 9, 1953 in Bhatwadgaon village of Beed district’s Majalgaon block, Shahir Salve arrived in Aurangabad as a student in the 1970s.

Marathwada had been under Nizam rule (prior to 1948), and the region’s development had suffered on many fronts including education. Against this backdrop, Dr. Ambedkar started the Milind Mahavidyalaya in Aurangabad’s Nagsenvan locality under the aegis of People’s Education Society in 1942. The Nagsenvan campus was developing as a centre for higher studies for Dalit students. Before Milind College, there was only one government college in all of Marathwada – in Aurangabad – that too only until inter! (Inter refers to the Intermediate degree, a pre-degree course.) Milind was the first college for undergraduate education in Marathwada. This new college was instrumental in creating a scholastic atmosphere in the region. At the same time, it transformed the political, social and cultural milieu. It brought life to a dying society and region – and an awareness of identity and sense of self-worth. Students started coming to Milind not only from all corners of Maharashtra but also from states like Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Gujarat. It was at this time that Atmaram Salve entered Milind as a student. The movement to rename Marathwada University (in Aurangabad), which started on this campus, was stirred by his illuminating poetry for two decades. In a way, he was solely responsible for the cultural activism of the Namantar (‘renaming’) and Dalit Panther movements.

The 1970s was a turbulent decade. It was the era of free India’s first generation of young men and women. A large number of youth were out with degrees in hand but disillusioned by the state of affairs since freedom (1947). Many events had had a huge impact on them: the Emergency; Naxalbari in West Bengal; the Telangana state movement; Jayaprakash Narayan’s Navnirman movement in Bihar; the movement for OBC reservation in Gujarat and Bihar; the recent Samyukta Maharashtra movement; Mill workers’ struggles in Mumbai; Shahada movement; Green Revolution; Marathwada Vikas Andolan; and the drought in Marathwada. The youth and the country were in turmoil, and the struggle for development and identity intensified.

Under the banner of Marathwada Republican Students’ Federation led by Dr. Machchhindra Mohol, the students who grew aware after arriving on the Nagsenvan campus, wrote a letter to the chief minister of Maharashtra on June 26, 1974, demanding one of the two universities in Marathwada be given Dr. Ambedkar’s name. But this demand for renaming ( namantar ) took an organised form when the Bharatiya Dalit Panthers got involved. Due to the conflict between Namdeo Dhasal and Raja Dhale, Dhale had announced the dissolution of Dalit Panthers. But a group called ‘Bharatiya Dalit Panthers’ was formed under the leadership of Prof. Arun Kamble, Ramdas Athavale, Gangadhar Gade, and S.M. Pradhan, to continue the work of Dalit Panthers in Maharashtra.

Atmaram Salve wrote about the newly formed Bharatiya Dalit Panthers:

मी पॅंथरचा सैनिक,

कांबळे अरुण सरदार

आम्ही सारे जय भीम वाले

अन्यायाशी लढणार

सैनिक भियाचे

नाही कुणा भिणार

अन्याय संपवून

पुढे पुढे जाणार

दलित, शेतकरी, कामगारा उठ,

करूनी एकजूट, उगारून मूठ

I am a panther soldier

Kamble Arun sardar

We are all Jai Bhim wale

Fighting for justice

Soldiers are not afraid

We don’t fear anyone

We will destroy injustice

And move forward

Dalit, farmer, worker, rise up

Let us unite and raise our fists

With this song, Salve welcomed the new Panthers, and he took on the responsibility of ‘Marathwada vice president’. On July 7, 1977, Gangadhar Gade, general secretary of the newly formed Bharatiya Dalit Panthers, raised the first public demand to name Marathwada University after Dr. Ambedkar.

On July 18, 1977, all the colleges were shut, and the All-Party Student Action Committee led a massive march, demanding the namantar of Marathawada University. Then, on July 21, 1977, savarna (caste Hindu) students of Aurangabad’s Government Engineering College, Saraswati Bhuvan college, Deogiri College and Vivekanand College, staged the first protest against the demand for renaming. There was a surge in protests, strikes and rallies – for and against the namantar . For the next two decades, Marathwada became a battleground of discord between Dalits and non-Dalits. In this field of battle, Atmaram Salve used the weapons of his shahiri , his voice, and his words, “against the caste war imposed on the Dalits”.

Atmaram Salve emerged at a time when the shahirs who had witnessed and experienced Ambedkar’s movement – like Shahir Annabhau Sathe, Bhimrao Kardak, Shahir Ghegde, Bhau Phakkad, Rajanand Gadpayale and Waman Kardak – were no longer present in the sociocultural milieu.

Coming in the post-Ambedkar period, the shahirs like Vilas Ghogare, Dalitanand Mohanaji Hatkar and Vijayanad Jadhav had not witnessed Dr. Ambedkar’s movement or the period of religious conversion. In a sense, they were clean slates. These shahirs from the countryside were introduced to Babasaheb (Dr. Ambedkar) and his movement through books. So their shahiri is visibly fierce, and Atmaram Salve’s songs are more so.

The matter of namantar was not only about a change of name. It was also about the newfound awareness of identity and the consciousness of being human.

When Vasantdada Patil, the chief minister, backed out of supporting the Namantar movement, Atmaram Salve wrote:

वसंत दादा, पॅंथरच्या लागू नको नादा

अन्यथा तू मुकशील गादीला

हे दलित आता घेतील सत्ता

आणि तू पडशील सांदीला

तुला सत्तेचा चढलाय माज

सोड तुझीबही तानाशाही

नाही चालणार हे तुझे जुलमी राज

Vasantdada, don’t pick a fight with us

You will only lose your chair

These Dalits will capture power

You will be left in a dusty corner

You are drunk on power

Look here, give up your dictatorship

Your despotic rule cannot go on

Watch Kesarabai Ghotmukhe sing ‘Hey Vasantdada, don’t pick a fight with us’

Atmaram Salve not only wrote the song but also performed it before thousands of people when Vasantdada Patil visited Nanded. A case was registered against him. A string of political ‘crimes’ continued for the rest of his life. From 1978 to 1991, until Salve’s death, cases were registered in police stations across Maharashtra, accusing him of offences ranging from fighting, obstruction in government work, rioting, and disturbing social harmony. And there were several murderous attacks on him. Chandrakant Thanekar, Salve’s friend and an associate from Deglur, recalls: “In 1980, he was attacked in Markhel village of Deglur block [Nanded district]. Salve was charged with attempt to murder of Dr. Naval after he questioned the doctor, who was accused of issuing a false death certificate in the case of a Dalit labourer Kale’s murder in Bennal village. For that, he, Rama Kharge and I were sentenced to two years of rigorous imprisonment and fined Rs. 500. A higher court acquitted us later.”

In the same Markhel village, Nagarbai Sopan Wazarkar, a 70-year-old woman, gave me a notebook of Atmaram Salve’s handwritten songs. She took it out of a clay pot, where it had been kept safe for 40 years. It was Nagarbai who had saved Atmaram’s life when he was attacked in Markhel. In another incident, traders of Majalgaon held a protest rally demanding the expulsion of Atmaram Salve for a bandh called by the Panthers. He was barred from entering Beed district after that. Tejerao Bhadre, from Mukhed, who used to play the harmonium when Atmaram performed, says: “Atmaram was passionate in his speech and provocative in his songs. Dalits loved to listen to him, but the savarna people took offence. They would even throw stones often. When Atmaram sang, the people sitting in the front threw coins towards the stage, while those offended by him threw stones. As a shahir , he was both loved and hated at the same time – and this was normal. But the stone pelting never stopped Atmaram from singing. He put all his rage into his songs and appealed to people to fight for their pride and dignity. He wanted them to fight against injustice.”

The police often shut down his programmes on the charge of disturbing social harmony, but Atmaram never stopped performing. Shahir Bhimsen Salve of Phule Pimpalgaon, who accompanied Atmaram during performances, recalls: “Atmaram Salve was barred from entering Beed district, but one night, he was to perform his shahiri within the district limits. Someone informed the police. They came and told Atmaram to stop. Then Atmaram crossed the river flowing through the village and went over to the other side. That part fell outside the district boundary, and Atmaram started started singing from there. People sat by the river, in the dark, listening to him sing. The singer was outside the district, and the audience was within the district borders. The police were helpless! It was hilarious.” Atmaram dealt with many such situations, but he never stopped singing. Singing was his life force.

Watch Shahir Ashok Narayan Chaure sing ‘Fight the battle for Namantar, my fellows’

Advocate Eknath Awad, founder president of Manavi Hakka Abhiyan (in Beed), has written in his autobiography Jag Badal Ghaluni Ghav ( Strike a Blow to Change the World , translated by Jerry Pinto) about an incident involving Atmaram Salve: “Atmaram was extradited from Beed under the charges of causing social disharmony, infuriating people through his shahiri . So, he was in Nanded. We started a district branch of Panthers and organised his jalsa . Parali Wes in Ambajogai has a large Dalit population. So the Jalsa was planned there. Atmaram was banned from entering Beed. So the police had kept a close watch. One PSI Kadam was all set to arrest Atmaram. We went and met him. ‘Arrest him after the performance,’ we said. He agreed. Atmaram performed with full energy. His songs reiterated the demand for namantar . PSI Kadam enjoyed the songs. He also praised him for being ‘a very radical shahir ’. But even while praising him, he was all ready to arrest him. Atmaram sensed it and got someone else to sit in his place on the stage and he ran away. PSI Kadam entered the stage to arrest Atmaram. But he was not to be found anywhere.”

On July 27, 1978, as soon as the resolution to change the name of Marathwada University was passed in Maharashtra Assembly, the entire Marathwada region turned into a holocaust for Dalits. All modes of transport were suspended within a day, and thousands of houses belonging to Dalits were torched. In some places, even as huts were set on fire, women and little children inside were burnt alive. In Nanded district, Janardan Mewade of Sugaon village and deputy sarpanch Pochiram Kamble of Tembhurni village were killed. Dalit police officers Sambhaji Somaji and Govind Bhurewar of Dhamangaon village in Parbhani district were also murdered. Thousands of Dalits were injured. Property worth millions was looted. Standing crops and farmlands were destroyed. In many villages, Dalits were boycotted and denied food and water. Thousands of people migrated from the villages to cities. Public and private damages totalled about Rs. 1.5 crores. Dr. Ambedkar’s statues were smashed in many places. Marathwada had transformed into a battlefield of caste warfare.

Atmaram wrote a song describing the magnitude of the caste violence in Marathwada, laying bare its brutality:

खेडोपाडी भडकला जाळ

नळगीरला जाळली बाळ

जीव घेऊन रानोमाळ

दलितांची झाली पळापळ

जातिवाद्यांनी केला छळ

दलितांना काम नाही, पेटेना चूल

थोडंसं शरीर झिजवा की रं

पेटलेली घरं ती विझवा की रं

पाट रक्ताचे भले वाहू द्या

मला उभं रक्ताने न्हाऊ द्या

अखेरची लढाई लढवा की रं

जरा क्रांतीचे बीज हे रुजवा की रं

In hamlets and villages, the fire flared

In Nalgir a little baby was burned

Holding on to their lives, rushing into woods

the Dalits dashed and ran helter skelter

Casteists harassed and tormented them

The Dalits had no jobs, their kitchen fires cold

Rise up people, rise up, won’t you

Douse the burning homes, won’t you

No matter if streams of blood flow

Let me bathe in this blood

Fight this last battle alongside me, won’t you

Sow these seeds of revolution, won’t you

This anti-Dalit atmosphere was not created in a day. It had its antecedents in the Nizam rule. Swami Ramanand Teerth was at the forefront of the fight against the Nizams. He belonged to the Arya Samaj. Though the Arya Samaj was formed to resist Brahminical oppression, its entire leadership was still Brahminical. And during the struggle against Razakars, this leadership had sown several prejudices against Dalits. Disinformation like ‘Dalits support the Nizam’, ‘Dalit neighbourhoods shelter Razakars’, angered the anti-Ambedkar savarna people and it was ingrained in their minds. So, Dalits had to face many atrocities during the police crackdown on the Razakars. A report on these atrocities against Dalits was prepared by Bhausaheb More, then president of Marathwada Scheduled Caste Federation, who sent it to Dr. Ambedkar and Government of India.

After Dr. Ambedkar, the battle for land rights was fought under the leadership of Dadasaheb Gaikwad with his slogan ‘ Kasel tyachi jameen, nasel tyache kay? ’ (‘Land to the tiller, but what about the landless?’) The Dalits of Marathwada were at the forefront of this struggle, and lakhs of women and men went to jail for it. Dalits took over lakhs of hectares of land for livelihood. The savarnas were not very happy with Dalits acquiring the common grazing grounds. That anger remained in their minds. The fight between Vasantdada Patil and Sharad Pawar also played a role in this. In village after village, the anger of savarnas was being expressed in the form of hate and violence. Rumours were afloat during the Namantar movement, like “The university will be painted blue”; “Degrees certificate will have Dr. Ambedkar’s photo”; “Dr. Ambedkar promotes inter-caste marriages, so these educated young Dalits will take away our daughters”.

“The issue of namantar of Marathwada University is included in the vision of Nav Baudhha [Neo Buddhist] movement. It is clearly a separatist movement demanding an independent Dalit existence, for which they are seeking help from Buddhist nations. They have also taken a position to relinquish Indian citizenship. Thus we need to take a clear and firm stand at the earliest.” The Namantar Virodhi Kruti Samiti passed this resolution at their meeting in Latur, and tried to separate the Dalits from their homeland. The Namantar movement was portrayed as a battle between Hindus and Buddhists, and such prejudices became common. And so, Marathwada continued to burn until the Namantar Andolan began, and it was in constant turmoil even afterwards. Twenty-seven Dalits were martyred during the Namantar movement.

The movement was not only about issues of existence and identity, but it also assimilated into social and cultural relationships. Its effects were seen during birth, marriage and death rituals. At weddings and during the last rites, people started giving slogans like ‘ Dr Ambedkarancha vijay aso ’ (‘Victory to Dr. Ambedkar’), and ‘ Marathwada Vidyapithache mamantar jhalech pahije ’ (‘Marathwada University must be renamed’). Shahir Atmaram Salve played a significant role in enlightening the people about Namantar and shaping the sociocultural consciousness.

Atmaram Salve’s life became all about Ambedkar and Namantar. He would say, “When the name of the university is officially changed, I will sell my house and farm, and use that money to write Ambedkar’s name in golden letters on the entrance arch of the university.” With his voice, words and shahiri , he carried the torch of enlightenment against oppression. Working hard to reach the goal of Namantar, he roamed the villages of Maharashtra for two decades on his two feet, without any means. Remembering him, Dr. Ashok Gaikwad of Aurangabad says, “My village, Bondgavhan in Nanded district, still doesn’t have an access road, and no vehicle reaches there. Atmaram came to our village in 1979 and performed a shahiri jalsa . He brought light to our lives with his shahiri , and his songs empowered the Dalits in their struggles. He called out casteist people openly. The moment he started singing in his powerful voice, people would throng to him like bees to a hive. His songs brought the ears to life, and his words revived a dead mind to get up and fight the hatred.”

Dadarao Kayapak from Kinwat (in Nanded district) has fond memories of Salve. “In 1978, Dalits in Gokul Gondegaon were being ostracised. To protest against this, S.M. Pradhan, Suresh Gaikwad, Manohar Bhagat, Advocate Milind Sarpe and I took out a morcha. The police had enforced Section 144 [CrPC], banning any gathering. A jalsa by Atmaram Salve was organised, and the situation was tense. Savarna people demanded that Shahir Salve and the Panther activists be arrested. They gheraoed Superintendent of Police Shrungarwel and Deputy Superintendent S.P. Khan, and the compound wall of the police guest house was set on fire. The atmosphere was charged, and the police fired. It claimed the lives of J. Nagorao, a close companion of Congress MP Uttamrao Rathod, and a Dalit conservancy worker.”

Shahir Atmaram Salve’s songs are replete with ideas of humanity, equality, freedom, fraternity and justice. Words like ladhai (fight), thingi (spark), kranti (revolution), aag (fire), rann (battleground), shastra (weapon), toph (canon), yuddha (war), nava itihas (new history) adorn his songs. The words signified his real life experiences. His every song was a war cry.

डागुणी तोफ, घेतली ही झेप

मनूची अवलाद गाढायला

चला नवा इतिहास घडवायला

क्रांतीचे रुजवूनी रोप

बंदुकीची गोळी, आज पेटविल होळी

मनूचा हा किल्ला उडवायला

Brought the cannon, took the leap

To bury the offspring of Manu

Let us make a new history

Planting the sapling of revolution

A bullet from a gun today, will ignite the Holi

To bring down Manu’s fort

Watch Tejerao Bhadre narrate ‘Kindle the fire within you, my Dalit brothers’

As an artist and shahir , Atmaram was not neutral. Nor was he provincial or narrow-minded. In 1977, there was massacre of Dalits in Belchhi, Bihar. He went to Belchhi and started a movement there. He was jailed for 10 days for it. He wrote about the massacre:

हिंदू देशात या, बेलचीला इथे

बंधू माझे जळालेले मी पाहिले

आया-बहिणी सवे, लहान बाळे

जीव घेऊन पळालेले मी पाहिले

In this Hindu country, at Belchhi

my brothers were burned, I saw this

mothers, sisters and children too

ran for their lives, I saw this

In the same song, he attacked the ideologically hollow and selfish politics of Dalit leaders:

कोणी काँग्रेसची झाली इथे बाहुले

कोणी “जनताला” तनमन वाहिले

वेळ आल्यावर ढोंगी गवई परी

त्या शत्रूशी मिळालेले मी पाहिले

Some became puppets of the Congress

Some dedicated their mind and body to the ‘Janata’ [Dal]

At the critical moment, like the hypocrite Gavai

I saw them join hands with the enemy

In 1981, a group of anti-reservationists pretending to be students went on a rampage in Gujarat to oppose the reservation of seats for Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe students in postgraduate education. There was burning, looting, knife attacks, teargas and shooting. Most of the attacks targeted the Dalits. In Ahmedabad, workers’ colonies of Dalits were set on fire. In rural parts of Saurashtra and North Gujarat, upper caste villagers attacked Dalit settlements. Numerous Dalits were forced to flee their villages.

Writing about this, Atmaram Salve said:

आज राखीव जागेमुळे

दीन-दुबळ्यांना छळता कश्याला

लोकशाहीचे पाईक तुम्ही

नीच मार्गाने वळता कश्याला

आज गुजरात हे पेटले

देश पेटेल सारा उद्या

हा भडकलेला वणवा

त्या आगीत जळता कश्याला!”

Today, for reserved seats

Why do you harass the weak

You are the beneficiaries of democracy

Why do you behave so despicably

Today, Gujarat is burning

Tomorrow,the whole country will

This is a blazing, raging fire

Why do you burn in it

Atmaram Salve did not perform for entertainment, money, fame or name. He believed that art is not neutral, or for entertainment, but an important tool in the fight for social, cultural and political change. He wrote more than 300 songs. We have 200 of these in written form today.

Lakshman Hire in Bhokar, Nagarbai Vajarkar in Markhel, Tejerao Bhadre in Mukhed (all in Nanded district), and Shahir Mahendra Salve from Phule Pimpalgaon (Beed district) have a collection of his songs. Many incomplete songs remain in people’s memory. Who wrote these songs? No one knows. But people keep humming them.

आम्ही सारे जयभीम वाले

आमचा सरदार राजा ढाले

We are all Jai Bhimwale

Our sardar [leader] is Raja Dhale

This ‘Dalit Panther lead song’, which was on the lips of every Panther member in those days, was written by Salve. The song plays in the hearts and minds of Marathwada’s people even today.

क्रांतीच्या या पेरून ठिणग्या

भडकू दे ही आग

कुठवर सोसू आबाळ

ह्रदयी भडकला जाळ

देऊ लागले ढुसण्या आईला

गर्भामधले बाळ

पाहून पुढचा काळ

भीमबाच्या शूर जवाना

येवू दे रे तुला जाग

Sowing these sparks of revolution

let this fire blaze

How long can we bear neglect

A fire rages in the heart

The child kicks the mother

from inside the womb

looking at the times ahead

Bhimba’s brave soldier

May you be awakened

Atmaram wrote this popular song (above). He also wrote the Marathwada Namantar powada . It is recorded in the index of his manuscript, but we don’t have a written copy of it. However, Rohidas Gaikwad, a Republican Party of India leader from Pune, and Vasant Salve, a veteran, missionary leader of the Ambedkarite movement, sang a few lines for me. During the boycott of Dalits in Bawda village of Indapur taluka (by upper caste villagers), Atmaram Salve had come to Pune and performed in many slum neighbourhoods. His songs revolved around the themes of collective spirit and sensitivity. Whenever Atmaram performed, Dalits from that place and the neighbouring villages would come, with bhakris packed, walking kilometres to attend the programme. Panther activists would address the audience after his performance. He became the ‘crowd puller’ for the Panthers and the Namantar struggle. Just as Namdeo Dhasal is the representative poet of the Dalit Panther era, so too Atmaram Salve is the representative balladeer of the Panther age. Just as how Namdeo does something ‘path breaking’ in his poems, Atmaram does it to the shahiri of the post-Ambedkar movement. Just as Namdeo’s poetry explains the Panther age, so does Atmaram’s shahiri elucidate the period. And just as Namdeo’s poetry confronts caste and class together, Atmaram’s shahiri takes on caste, class, and gender oppression at the same time. The Panthers influence him, and he influences the Panthers and the people. It was under this influence that he left everything behind – higher education, job, home, his everything – and followed his chosen path fearlessly and selflessly.

Watch Sumit Salve sing ‘How long will you wrap the age-old blanket around you?’

Vivek Pandit, a former MLA from Vasai, was a friend of Atmaram Salve’s for over two decades. He says, “Fear and self-interest – these two words were never in Atmaram’s dictionary.” Salve had a great mastery over his voice and words. He also had a firm grip on what he knew. Besides Marathi, he was fluent in Hindi, Urdu and English. He composed some songs in Hindi and Urdu. He even wrote and performed a few qawwalis in Hindi. But he never commercialised his art, never brought it to the market. Turning his art, his words and his powerful voice into a weapon, he came out like a soldier fighting against caste-class-gender oppression – and continued to fight alone until his death.

Family, movement and occupation are the sources of mental support for an activist. Bringing them together, a people’s movement needs to create an alternative space where activists and people’s artistes can survive and sustain themselves – where they are not isolated and lonely.

No constructive and organisational steps have been undertaken in the Ambedkarite movement to protect artistes from slipping into mental depression, or to help them when they are depressed. So, naturally, what happened to an artiste like Atmaram Salve, happened.

Later in life, he was disappointed on all three levels. His family broke up due to the movement. His addiction (to alcohol) got worse. Towards the end, he became delirious. He would stand like a performer and start singing anywhere – in the middle of the road, at the town square, on anyone’s demand. In the midst of his addiction, this shahir who fought for Namantar died a martyr in 1991 without writing the university’s new name on the arch in golden letters.

This story was originally written in Marathi. Translated into English by Medha Kale.

Translation of powadas (ballads): Namita Waikar.

The author would like to thank Lakshman Hire from Bhokar, Rahul Pradhan from Nanded, and Dayanand Kanakdande from Pune for their help in reporting the story.

This multimedia story is part of a collection titled ‘Influential Shahirs, Narratives from Marathwada’, a project implemented by India Foundation for the Arts under their Archives and Museums Programme in collaboration with People’s Archive of Rural India. This has been made possible with part support from Goethe-Institut/Max Muller Bhavan New Delhi.