Last month, in a case concerning two Telugu news channels, the Supreme Court said it was time that the court defined the limits of sedition law. FIRs were registered against these channels for running a story related to Covid-19 management in the state. The court stayed the coercive action against the media channels and termed the FIR as “muzzling of the press.” Just few days after that in a sedition case against journalist Vinod Dua, the Supreme Court said every journalist is entitled to protection under the Kedar Nath Singh case, similarly, every prosecution under section 124A of IPC (Sedition) should meet the standard laid down in the Kedar Nath Singh case.

Recent data suggests that sedition cases have been on rise since 2014, when the Modi government came into power.

Through the judgment in case of Kedar Nath Singh vs State of Bihar (1962) the SC had limited the scope of section 124A and restricted punishment only to the cases where there is an incitement of violence or public disorder. While the recent judgment in the case of Vinod Dua has been appreciated as it reiterates this principle, many people have also expressed serious reservations about the effectiveness of the judgment. In an article in The Leaflet senior advocate Mihir Desai calls the judgment a “mixed bag”. He argues that diluting or further reading down this section is not going to do any good and the only way to deal with this pernicious section is to strike it down.

Recent data suggests that sedition cases have been on rise since 2014, when the Modi government came into power. Data from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reveals that from 2016 to 2019, sedition cases have increased by 165 %. A database maintained by the website Article 14 also shows a similar increase. It states that out of 11,000 individuals implicated under sedition from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2020, 65% were implicated after 2014. It also states that there is an increase of 28% in the number of sedition cases filed each year between 2014 to 2020, compared to the yearly average between 2010 to 2014.

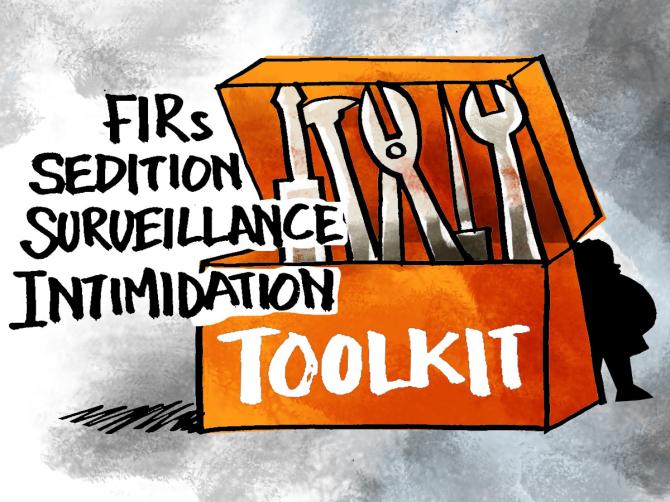

In this scenario, it should not be surprising that BJP leaders have been talking about amending section 124A to make it more stringent. It has been used to target not only journalists but students, activists, artists or anyone who speaks up against the government. One may ask if the Kedar Nath Singh case has restricted the scope of this section, how are the cases under this section on a rise.

Sedition is a cognizable offence which means that police can arrest the accused without any warrant from the magistrate.

The truth is that even though most of the cases where section 124A is charged do not qualify the basic requirement of incitement to violence, the police do not necessarily take this into account. Sedition is a cognizable offence which means that police can arrest the accused without any warrant from the magistrate. It is also a non-bailable offence and hence the process of getting the bail is longer and, hence, serves as an important tool to suppress dissenting voices.

Earlier this year, climate activist Disha Ravi was arrested for sharing the toolkit for farmers’ protest. The circumstances of her arrest and the manner in which the Delhi police executed aptly demonstrates what a person accused under sedition may have to go through while facing the law enforcement officials. Disha was arrested by the Delhi police from her house in Bangalore and was produced before a magistrate in Delhi instead of producing her before the nearest magistrate, as required by law. She was also not given access to proper legal counsel. Disha spent several days in custody before she was granted bail even though her speech or actions may not have satisfied the criteria of incitement of violence.

Disha spent several days in custody before she was granted bail even though her speech or actions may not have satisfied the criteria of incitement of violence.

In an article in Newlaundry, Kalpana Sharma argues that even though the judgment by the SC in Vinod Dua’s case is significant, it may not benefit journalists. She states that what the court held in this case was already clear 60 years ago in Kedar Nath Singh’s case, and yet the police and government continue using the provision against the journalists even today. The only recourse in such cases is to approach the higher courts, which may not always be affordable for all. She further argues that such a law should be consigned to the dustbin of history.

The constitutionality of the section 124A of IPC is under question in an ongoing case in the Supreme Court. On April 30, 2021 the court issued a notice to the Central government to respond to a petition filed by two journalists. Will the Supreme Court reconsider its decision in the Kedar Nath Singh case, which although limited the scope of the law, upheld its constitutional validity?