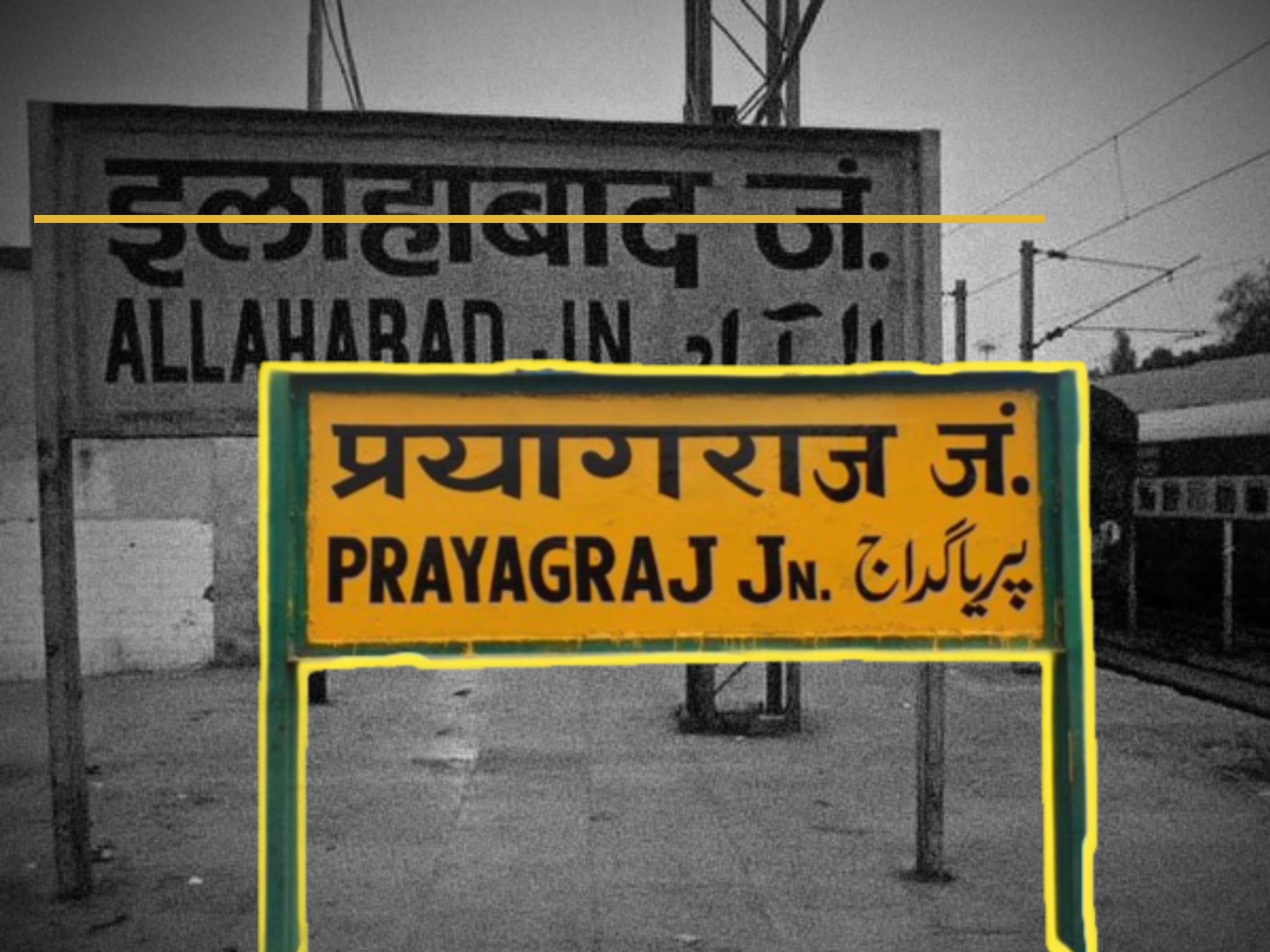

In the recent past, we have witnessed a drastic increase in the practice of renaming cities, railway stations, and other public places. Some changes were made to reflect the widely used vernacular pronunciations (Mangalore to Mangaluru, Mysore to Mysuru), others involved restoration to their pre-colonial names (Rajahmundry to Rajamahendravaram), while still others were carried out for populist reasons (Chennai Central Railway Station to Puratchi Thalaivar Dr. M. G. Ramachadran Central Railway Station). Some name changes, however, betray a creeping saffronisation of our public spaces (Allahabad to Prayagraj, Faizabad to Ayodhya, Gurgaon to Gurugram, Mughalsarai Junction to Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Junction, etc), with the most recent declaration of Dragon fruit’s new name as “Kamalam”, supposedly because of its shape.

There have been vigorous debates on name-changing on social media, newspapers, magazines, and in academia. A typical justification is that such renaming reclaims past glories and cultures that had been suppressed by Muslim ‘invaders’. This 2-part article tackles a series of interlinked questions that arise from the above justification. How is this renaming different from renaming places with colonial origins (Madras to Chennai, Bombay to Mumbai, etc.)? Is the practice genuinely about reclaiming forgotten cultures and redressing a wounded civilization? More importantly, have the pre-existing, ancient cultures been forgotten or violently erased by the dynasties frequently referred to as ‘Muslim invaders’? By imagining them in such religious and predatory terms, the question is whether this phenomenon is uniquely grounded in the religiosity of these ‘invaders’. This final question is important because locating their actions in their religious beliefs ensures that their Islamic culture can be shown as being in complete opposition to pre-existing indigenous cultures. These supposedly besieged cultures are linked to peoples mostly practising various strands of Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, and Jainism. The article contextualises the motives behind the kings’ destructive tendencies, grossly exaggerated to begin with, and how their behavior was part of established political norms of medieval warfare.

Are we genuinely redressing a wounded civilisation?

Reviving forgotten cultures and destroyed memories through changes in nomenclature is superficial to begin with. It wishes to cater to a specific brand of cultural nationalism and Hindu chauvinism. It aspires to create a sense of taking ownership of the nation’s destiny in the context of ‘barah sau saal ki gulami ki maansiktaa’ (1200 years of slave mentality troubling us), as articulated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the Lok Sabha. Hindu nationalism models itself on the kinds of nationalism that have evolved in Europe since at least the early eighteenth century. In Britain and France, these nationalisms emerged ‘in response to contact with the Other, and above all in response to conflict with the Other’.1 The specific demonising of Muslim rulers and invaders has been documented extensively as an attempt at Othering the Muslim community.

Colonial historiography of medieval India portrays Islamic rulers as tyrants, intent on eradicating indigenous belief systems and peoples. For example, temple destruction was portrayed as a widespread phenomenon flowing naturally from the iconoclastic beliefs of Muslim rulers. However, one of the reasons Muslim rulers demolished temples was to signal deference to sharia. This served to enhance their standing in the wider Muslim world, with the rulers in West Asia being far more prolific in destroying shrines. This is similar to the renaming of places, symbolising the deference of the governments to the Hindutva worldview. They need not do anything beyond giving bureaucratic approvals and claiming redressal of past wounds.

This hurt felt by many in current times is rooted in mythologized memories of what actually happened. The question of a wounded civilization can be turned on its head to explore structural injustices suffered by historically oppressed castes and communities. This doesn’t refer to violence and exploitation alone but to the stifling of subaltern voices, memories, and oral histories. Jainism, Buddhism, Sufi and Bhakti cults rose as organic revolutions within society to counter the excesses of Brahminism and caste-based hierarchies.

How do we redress the erasure of works shaped by these revolutions? Some of the major Buddhist and Jain works in the literatures of South India are irretrievably lost. Despite coastal Andhra being a major centre of Mahayana Buddhism in the first millennium CE, the earliest documented literary work in Telugu is a poetic version of the Mahabharata by Nannayya from the beginning of the eleventh century CE. The highly refined nature of this work suggests that there once existed a corpus of great Telugu literature preceding it. One credible reason for this vacuum is that this ‘lost’ literature ‘was Buddhist and Jain in character and there was a deliberate suppression of such literature with the revival of Brahminism’.2

A sincere revival of erased processes and places would involve reforming the Brahminical names of places. More than a hundred villages are named Agraharam or Agrahara in South India. Brahmins and upper castes have been dominant and hegemonic through much of Indic history and epistemologies, determining how religious or social spaces are named and shaped. Noted director Pa. Ranjith, in his interview with film critic Baradwaj Rangan, points out how the main part of his village was called oor and is inhabited by the upper castes. His own area, a Dalit habitation on the outskirts, was called cheri or colony. When someone asks him about his village, he responds with the name of a place to which his own entry and access are highly restricted. And when someone asks about him in the village, they reply that he’s from the colony. There is this deep fissure in how public spaces are named and claimed, depending on the caste one belongs to.

While it is not an uncommon practice for villages, towns, cities, and places to be named after castes, be they dominant or oppressed, upper caste names are far more common than Dalit names, reflecting their hegemony. Nor is it a symbol of empowerment if a village takes its name after a Dalit caste. Such nomenclature becomes an easy marker to identify the caste of an individual hailing from eponymous villages. Their naming tends to influence how they and their inhabitants are perceived, and how they evolve over the years. And some villages are associated with some castes without being eponymous. In the Tamil movie Pariyerum Perumal, the Dalit protagonist mentions the name of his village but never his caste. Yet the other characters instantly recognize his caste.

In 2018, there were agitations around Vadhu Budruk and Bhima Koregaon, two villages in Maharashtra. Vadhu Budruk is the village where Sambhaji was cremated by Govind Mahar. According to legend, Sambhaji was mutilated and thrown into a river. Govind Mahar gathered his body parts and ensured that his last rites were performed. Memorials to Sambhaji and Govind were erected by the Mahars of the village. This version is contested by upper caste Marathas. Bhima Koregaon was the site of the victory of a British regiment, composed mostly of Dalit Mahars, over the Maratha army. Nationalist historiography portrays this event negatively, but for Dalits, this is cherished history, a moment of coming into their own against the vaunted Maratha warriors. As Pratap Bhanu Mehta notes, what is at stake in both these agitations is ‘not just a Dalit right to their own histories…but a Dalit challenge to other histories’.

Do we adequately teach in our schools about leaders and revolutionaries from Shudras, Dalits, or Adivasi communities? As Indian society becomes more homogeneous in how it consumes and lives, do we even have mechanisms to record disappearing ways of life of people transitioning from the margins to the centre? Genuinely remembering and reclaiming what has been forgotten would entail funding research on the past, backing diverse lines of inquiry, organizing conferences, and supporting restoration and excavation work.

But our pre-modern architecture continues to rot away, Islamic or otherwise, with little state protection. Karnataka alone has an estimated 30,000 historical structures that remain unprotected and under threat of being encroached upon. There have been inordinate delays in funding and in excavation work in the archaeologically significant area of Keezhadi in Tamil Nadu. This was followed up with a highly questionable transfer of the lead archaeologist at the site.

Appointing individuals with questionable credentials to head institutions for historical and cultural research only weakens purposive inquiries into the past. Besides, the funding of research in social sciences, including history, has historically been low. This is in contrast to much higher allocations for the natural sciences. Despite an increase in higher education funding by Rs. 2450 crores in the 2019–20 Union Budget, the allocation for Councils/Institutes for Excellence in Humanities and Social Sciences (Indian Council of Social Science Research, Indian Council of Historical Research, Indian Council of Philosophical Research, Indian Institute of Advanced Studies, etc.) has only stagnated over the last 5 budgets.

But perusing other budget heads in the past decade (2010-20) presents a more complex picture. Spending on the Ministry of Culture has nearly doubled with the Archaeological Survey of India seeing its budget double from ₹422 crores to ₹1001.77 crores (revised estimates) between 2010-11 and 2019-20 respectively. Language is the most intrinsic part of any culture and development of languages has also seen doubled spending over the last 10 years. However, skewed spending on Sanskrit and Hindi at the expense of other languages with equally significant literary traditions has been a disturbing trend of late.3

‘Panting for some heaps of stone’: the futility of name-changing

In the pursuit of power, most rulers in the subcontinent, whether democratic or despot, have used religiosity as a means to strengthen their legitimacy. The size of the subcontinent and the diversity of its peoples have ensured that pushing religious dogmas as policy never allows consolidating power for long. Moderation had to be the political norm of governance, with extremist kings and dynasties perishing quickly.

We cannot wish away historical truths and their contexts just as we cannot disregard deeply felt beliefs built upon a discourse of invasions and Islamic subjugation. However, changing the names of places or destroying a few dozen temples will not satisfy or rile up a population for long. Places flourishing under a certain name for centuries will continue to be referred to by their old names. Historical memories cannot be as easily manipulated as nomenclature.

Renaming places is an act full of symbolism, signaling the rewriting of Indian history, putatively freeing it from centuries of bondage. In claiming to write a new history in the image of the majority, it creates the heady illusion of taking control of the country. And yet, symbolic acts will only go so far in assuaging the memories of a people, constructed or real. Historiography that interprets these symbolic acts as a larger clash of civilizations creates a discourse rooted in hatred of the Other. This is ironic since the Hindu worldview, for thousands of years, did not rely on the existence of an Other for sustenance. It was able to assimilate all manner of foreigners, whether invading Huns or migrating Jews, by giving them a place in its extremely diverse and graded system of caste hierarchies. Islam presented the first major challenge for this sort of assimilation, retaining its own worldview and even attracting converts.

In the subcontinent’s history, identity has been an important marker but never the paramount one, especially in matters of kingship and governance. The current renaming is a top-down process, with a majority of the people having little appetite or aspiration for these new names. What has been set in motion is a dialectical process. Renaming, instead of emerging through popular demand, serves as a catalyst to make the masses conscious of their identities. It pushes people to view themselves and their social history through a religious lens. Ensuring communal harmony and all-round development for society takes a backseat. Rather than there being any disjuncture between Hindutva and development, Hindutva becomes development.

Participating in Mughal campaigns in South India, conquering fort after fort, one of the soldiers remarked how Aurangzeb was vainly ‘panting for some heaps of stone’.4 By the end of his life, Aurangzeb is left pondering his legacy of conquests. When he steps down, Prime Minister Modi might well ponder his own legacy in this area: this fetishism of renaming as an exercise in bureaucratic approvals and hollow symbolism, be it exotic fruits or entire geographies. We are trapped between what we would like to be and what we actually are, between making our tryst with destiny and hoping to fulfill it by tinkering with the spelling of destiny.

Notes:

Colley, Linda. 2005. Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707–1837, Yale University Press.

Rajamannar, P. V. 1957. “Telugu Literature.” In Literatures in Modern Indian Languages, edited by V. K. Gokak, 144–51. The Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting

Source: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/

Truschke, Audrey. 2017. Aurangzeb: The Life and Legacy of India’s Most Controversial King. Stanford: Stanford University Press.