In a small village in Kerala, people begin to feel threatened by an invisible rooster that crows at odd hours. It offends the sentiments of all those who are religious, political, patriarchal, exploitative, fanatical and homophobic. Naturally, there are many baying for its blood. The witch-hunt that ensues fuels suspicions that the invisible cock might even be a human; an anarchist who is trying to destabilise the nation with help from outside.

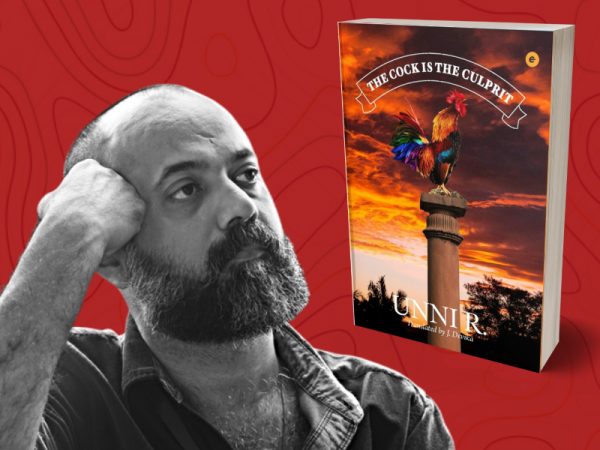

A stunning tale, as N S Madhavan calls it, The Cock is the Culprit — written by Unni R and translated by J Devika — does an astute job of exposing the dark underbelly of Kerala society.

The Indian Cultural Forum spoke to Unni R about the book, his thoughts on translation, Kerala, and more.

ICF: The “cock” in the book is an allegory for a lot of things and is deeply multi-layered. Do you consider the use of allegory or political satire as the sharpest or safest way to respond to the political climate we’re in at the moment in India? Itself a sign of our times, perhaps?

Unni R (UR): We have only learnt about fascism in history or talked about it in intellectual circles. We hadn’t experienced fascism as a reality (By “we”, I am talking only about the people who fear fascism, who have analysed it politically, and who have undergone the cruelty resulting from it). However, in today’s India, we can observe this fascism in the politics of Hindutva. In such a political climate, the language adopted by a writer becomes very pertinent. As a writer, I believe that we necessarily have to talk about certain topics. Silence is not only cowardly but also a kind of espionage for the State. Even your language is misinterpreted. You are labelled anti-national. And by doing so, the government is able to instantaneously dismiss the truths that you say. It is in this context that I thought about the possibility of satire. Cartoons were one of the most effective forms of expression during the Emergency. The Cock is the Culprit tells the story of present-day India. Actually, it tells the story of not just India, but that of any autocracy in the world.

ICF: Critics consider your writing to be part of a new age in Malayalam arts, literature and cinema, which has emerged in the last few years with novel ideas, methods, politics, and intensity. CS Venkiteswaran sees you as belonging to an entire generation of young Malayali writers with an urge to expose the Kerala society’s underbelly — including KR Meera, S Hareesh, among others. Do you too feel that there is a new wave? What do you think makes your generation of writers different from those progressive strands preceding it?

Also Read | A Blot on our National Pride

UR: The Seventies saw a surge of Modernism in Malayalam literature. But there weren’t any major shifts in writing at the end of the decade. The new generation of writers have created a movement that totally rejects the sensibilities created by Modernism. Our generation has not had to exist under the yoke of any particular movement or sensibility. We are free in thought and expression. Kerala society, that calls itself “modern”, has not been able to digest the sexuality in my stories. Similarly, the dalits and their history that appear in my stories is considered distasteful in the eyes of society. Our writing is also a rebellion against a society that is elitist.

ICF: Writers are often wary about their works getting translated into other languages, simply because of the probable risk of certain nuances and ideas getting lost in translation. What is your take?

UR: Yes, people often talk about the loss of organic subtleties in translation. Marquez has commented on the exactness and attention to detail that characterises Edith Grossman’s translations of his works. He talked about how she was able to retain the beauty of his writing in her translated versions. This happens when Translation becomes Transcreation. Lydia Davis and Michael Hofmann are outstanding translators. J Devika, the translator of my works One Hell of A Lover, and The Cock is the Culprit, falls in this category. She does not see translation as merely a job. A known feminist and academic, she brings an extension of her thoughts and convictions to her translation. Besides, she does not translate books that are incompatible with her beliefs. As a writer, I am totally satisfied by Devika’s translations.

ICF: Your work reflects a deep sense of belonging and attachment to your roots — a little village in Kerala. In what way have they shaped yourself and your writing? Who all have been your inspirations — from within Kerala and outside?

UR: I was born in Kudamaloor, a small village in Kottayam district, Kerala. It falls in the vicinity of Aymanam, which gained prominence through Arundhati Roy’s book. The first thing that my village taught me was an entitled belief in my caste. However some books which I accidentally came upon, introduced me to reading. It opened a completely different world for me. The books of Paul Zachariah and O V Vijayan took me to a place that I had never seen. Although I didn’t understand the depth of those works at that age, it signalled the beginning of a new journey. I started seeing the people around me as the characters in an enormous novel. Dogs, cats, beggars, prostitutes, libraries, Quran, Upanishad, and myriad other things have influenced and inspired me immensely. Arogya Niketan and Aranyak are books that have seeped into my blood during my college days. Cervantes, Marcel Proust and Flaubert are names that echo in my heartbeat.