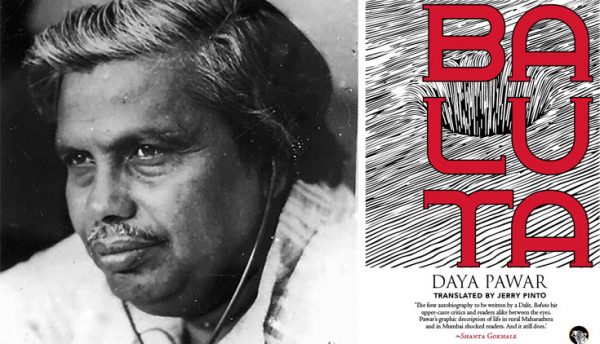

It was perhaps in 2006 that I first encountered Baluta, Daya Pawar’s autobiography, when a friend gave me his copy of it. Fourteen years back, in my early twenties, I was still trying to make sense of my vagrant life. To be very honest, the book seemed to offer me nothing then; perhaps because I wanted to avoid what it put forth. So I totally missed the its biggest insights for my vagrant days, while I made my escape from a life born and raised in a dalit basti.

Baluta, in many senses, is the universal cry of a man who wants to break free from the world he has inherited; which shackles him. It is a psychological attempt of a man to make sense of the horrible phenomena he is caught up in, until he arrives at the realisation that unless the world frees itself there is no freedom for him; that there is only struggle, a constant war, between him and the world.

Baluta was the first daring attempt to tell the world, with brutal honesty, how sick it is and how sick it had made the one who wants to break free of himself and the world.

Also read | ‘Mother’ Resurrects Lost Humanity in Nagraj Manjule’s Poems

Critical theorist Frantz Fanon wrote in Black Skin, While Masks, “Ontology does not allow us to understand the being of the black man, since it ignores the lived experience. For not only must the black man be black; he must be black in relation to the white man.”

Baluta indicates precisely this. We find that it is not at all the attempt of a being to arrive at clarity, but an attempt to arrive at the clarity of confusion. It is an attempt to tear apart the web of complexity in which oppression, too, is not clearly visible, and hence becomes difficult to attack.

As this writer explained in the EPW last year: “Baluta marks the beginning of the exploration of class in caste, how this newly formed class within caste changed the way we look at life, and how it had deracinated Dalits from their cultural heritage. Baluta became popular among both Dalits and Savarnas because it provided a scope for both communities to introspect.”

Baluta does not make us free. It makes us realise the complexity of our victimhood; both dalit and savarna. Baluta rejects the ontology of dalits artificially constructed by a brahmanical world. Yet it honestly accepts the demonisation of that being—the ‘invisible man’1—who has been cruelly produced by the world from the moment he dared to break free from being ‘non-existent’—a phenomenon begotten by the practice of untouchability.

By journeying constantly, and without apology, into the emotions and reactions of its protagonist in caste society, Baluta paves our way to see that ‘inferiorisation’ only exists among men who nurture ‘superiorisation’ within themselves. Such men develop an utterly neurotic condition, and it is that which prohibits them from behaving ‘humane’. Not only does a victim suffer from oppression; even the oppressor suffers from a neurotics which makes him into a mere parasite.

Also read | The Casteless Collective: Musicalising Anti-Caste Conscience

Fanon explains this to us in Black Skin White Masks:

“I am white; in other words, I embody beauty and virtue, which have never been black. I am the colour of day.

“I am black; I am in total fusion with the world, in sympathetic affinity with the earth, losing my id in the heart of the cosmos—and the white man, however intelligent he may be, is incapable of understanding Louis Armstrong or songs from the Congo. I am black, not because of a curse, but because my skin has been able to capture all the cosmic effluvia. I am truly a drop of sun under the earth.

“And there we are in a hand-to-hand struggle with our blackness or our whiteness, in a drama of narcissistic proportions, locked in our own particularity, admittedly with a few glimmers of hope from time to time that are constantly at risk from the source.”2

Baluta tells us that the most violent development of Fanon’s understanding of identities, the artificial discourse which deracinated humans from their real ‘being’, is a part of a cosmic ecology: we are all human, but now we see ourselves in categories. We are victims of these categories and hence the intention of our relationship with each other has now acquired pre-human connotations.

In the appendix, Pawar writes, “Dalit youth experience a thrill in loving Savarna women. While studying black literature, one finds that black men have tremendous attraction for white women. This may be the emptiness of the ages. It must be a longing for something which cannot be gained easily. It also must be a sign of seeking revenge, mentally.”3

Fanon explains it somewhat like this: “Since I am abandoned, I shall make the other suffer, and abandoning the other will be the direct expression of my need for revenge.”4

Also read | Shindeshahi: Music More Important than Philosophy

We find a very vivid illustration of this in Baluta, which introduces us to the genesis of “men being pushed away from appreciation of their labour” and, essentially, from “feeling” it, in caste society.

One instance in the autobiography provides substantial insight into what Fanon means by the “process of alienation” and the “birth of revenge”, within both the oppressor and the oppressed.

“In reality,” Pawar writes, “The land on which the Maruti temple stood belonged to the Maharwada. The Mahars had also laboured to build the temple. But once Maruti was ensconced and the temple consecrated, the Mahars had to be kept away.”5

Thus, when you are kept away from your “creations” for centuries, and your rights over them are taken away, then the poison of revenge also damages your ability “to love” and “to be loved”. You are in love, yet you feel abandoned. You are being loved, yet you feel abandoned, since the privileged person who is loving you cannot fully assimilate into your history—at least, not the painful part of it. Only after reading the history of the “emotions and feelings” of these abandoned men, or carrying the burden of their abandonment, can we reach a close understanding of Baluta and its purpose.

After taking us through many such instances, Baluta convincingly leads to Fanon’s vision of breaking free from the narcissistic self.

Pawar proclaims:

“Dagdu Pawar is now walking away, his shoulders slumped. Like Christ he carries a heavy cross, and it seems to have deformed him. Unlike Christ, he does not have a halo around his head; his welts have begun to fade.

“Slowly, he gets lost in the world.”

We can see Fanon’s “abandoned man” finally embrace his position, his history, and his “identity-less” self. He may not bear the “halo” of acceptance or of being celebrated—he does not even care about those—but he is slowly attempting to be a part of the social, of nature and the cosmos, as an equally essential being. He is the world; the world is he.

Notes:

1 A member of ex-untouchable community

2 Black Skin, While Masks by Frantz Fanon, 2008, Grove Press

3Baluta, by Daya Pawar, 1978, Granthali

4 Black Skin, While Masks by Frantz Fanon, 2008, Grove Press

5 Baluta, by Daya Pawar, 2015, page.133, Speaking Tiger