This is the second of a three-part series tracing the leading events in Assam’s politics of language, religion, ethno-nationalism and citizenship from the nineteenth century to the present day.

- 1948: Eknath Ranade is posted as prant pracharak (provincial missionary) of the RSS in the North-East. He sets up Vivekananda Kendras for “cultural expansion” in the region and seven residential schools in the North-East Frontier Agency, today Arunachal Pradesh. The RSS’s work is directed by people from outside the region. The first local prant pracharak in Assam is not appointed till 2014.

- 1950: The Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act is passed, enabling the central government to order the removal from the country of any person “having been ordinarily resident in any place outside India”. The government may delegate the function to subordinate agencies at the central or state level. The delegated agency is protected from legal action in implementing its duties. Anyone who “harbours” a person so identified by the government is liable for penalty.

- 1951: Independent India’s first census is accompanied by an NRC process in Assam. Completed within three weeks, as a sideline to the census, it is a hasty, shoddy exercise, but its results form the basis of demands to identify “outsiders” in the decades ahead.

- 1955: The Citizenship Act is passed, outlining the terms for citizenship by birth, descent, registration, naturalisation, incorporation of territory, etc. It will be amended after the Assam Accord in 1985, with a special provision for the state (see below).

- 1960: The Assam Official Language Act is passed, halfway through the first term in office of Bimala Prasad Chaliha (who remains chief minister till 1970). Writer and politician Nilamoni Phukon, an MLA at the time, says: “All the languages of different communities and their culture will be absorbed in Assamese culture. I speak rather with authority in this matter regarding the mind of our people that this state government cannot nourish any other language in the province. When all the state affairs will be conducted in Assamese, it will stand in good stead for hill people to transact their business in Assamese with their Assamese brethren.” The debate and passage of the Official Language Act are accompanied by riots. Following a proposal that Bengali, along with Assamese, be adopted as the official language, violence erupts against Bengali Hindus. Eventually, the government agrees to a demand of the ‘Bhasha Andolan’ of Sylheti speakers to grant Bengali official status in the Barak Valley. During his second term, Chaliha claims there are 300,000 illegal immigrants from East Pakistan in Assam. Political resentment and “son of the soil” movements against Axomiya dominance arise in various areas. The Nagas are the first to be taken out of Assam (1963), followed by the Khasi, Jaintiya and Garo hills, which form Meghalaya (1972), and the Lusai Hills for Mizoram (1987).

- 1964: The Foreigners (Tribunals) Order is issued by the central government’s ministry of home affairs. It empowers the central government to establish tribunals to “determine as to whether a person is not a foreigner”. A tribunal is to consist of “persons having judicial experience” and will have “the power to regulate its own procedure”. Endowed with the powers of a civil court, it may summon any individual, require the production of any document, and call on witnesses as it sees fit.

Such tribunals to weed out “infiltrants” had been set up during the Indo-China conflict of 1962. However, the immediate reason for the establishment of tribunals by executive order in 1964 is the tense state of relations between India and Pakistan. Pakistan has threatened to go to the UN with the claim that India is pushing its citizens into East Pakistan to foment trouble. The tribunals are India’s attempt to up the ante by identifying Pakistanis on Indian soil. Since the immediate purpose of the tribunals is to identify foreigners, their procedures exist to promote this end. - 1967: The All Assam Students Association is renamed the All Assam Students Union (AASU). It will spearhead the protest during the Assam Agitation, twelve years later.

Also read | Part I : Assam and the CAA: A Pre-Independence Timeline

- 1970: Gauhati University’s Academic Council passes a resolution requiring the introduction of Assamese as the medium of instruction. The Council concedes that students may write their examinations in Bengali and English as well as Assamese. Protests led by AASU demand the withdrawal of Bengali as a permitted language. Riots against Bengali Hindus follow.

- 1972: The Indo-Bangladesh Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Peace is signed between Mujibur Rahman and Indira Gandhi. In separate talks, the leaders agree to make March 25, 1971, the cut-off date to distinguish citizens from illegal aliens.

- 1976: The coinage of an electoral alliance of “Ali-Coolie-Bongali” (or Muslim, migrant worker and Bangladeshi) vote-banks is attributed to Congress politician Dev Kanta Barooah. The attribution may or may not be correct, but the phrase swiftly comes into pejorative use. The slogan “Ali, coolie, Bongali/ Naak sapeta (snub-nosed) Nepali” becomes part of anti-outsider street protests.

- 1978, March: The Janata Party wins elections in Assam. The Janata government includes the Jana Sangh, precursor to the BJP; by 1975, every district in Assam had an RSS shakha. In October 1978, the state government appoints Hiranya Kumar Bhattacharyya (then DIG police) to head the Border Police Division, and he is joined by Premkanta Mahanta, who is appointed SP of the division. In his 1994 memoir, Mahanta writes: “I affirm that…the six-year-long Assam movement [1979 to 1985] would not have taken place if we hadn’t come together at this point.”

- 1978, October: Chief election commissioner, S.L. Shakdhar, states in a meeting that the electoral rolls for Assam have been inflated to the tune of 70,000 voters by the inclusion of “illegal immigrants”. The Assam Sahitya Sabha and the AASU direct a campaign against all East Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Nepali immigrants post-1951.

- 1979, March: The death of Hiralal Patowari, MP from Mangaldoi, necessitates a bye-election. Under the guise of preparing the electoral list, Hiranya Kumar Bhattacharyya and Premkanta Mahanta launch a publicity campaign encouraging people to denounce voters from their booth as “foreign nationals”, so that their names may be struck off the rolls. By the time the election commission acts on complaints against the officers, they have already processed complaints against over 47,000 voters and identified close to 37,000 of them as foreigners. The issue proves a catalyst for the Assam Movement.

- 1979–85: The Assam Agitation, also termed the Assam Movement and Anti-Immigrant (bohiragata) Movement. One of its major demands is that the NRC of 1951 be the benchmark to identify foreigners. Prafulla Kumar Mahanta is named president of AASU in 1979. In August the same year, the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP) is formed. It is constituted by the AASU, and joined by the Assam Sahitya Sabha, among other organisations. Talks with the centre break down repeatedly on the issue of the cut-off date for citizenship, with Indira Gandhi’s government adamant on keeping it March 25, 1971 – after the formation of Bangladesh – and the AAGSP and AASU insistent on 1951.

The United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) is formed – in 1979, by its own account – becoming active from 1983 onwards. A militant outfit, it aims at Assam’s independence from India.

During the Agitation, the RSS deploys its student wing, the ABVP, to focus Axomiya ire away from Nepalis, Marwaris and Bengali Hindus, and direct it towards Bengali Muslims alone. Whereas the AASU demands the removal of all “Bangladeshis” from the electoral rolls, the RSS wants only the Muslims removed.

In 1980, the All Assam Minority Students Union (AAMSU) is formed, to counter the AASU, and the big-tent idea of Axomiya identity begins to crumble.

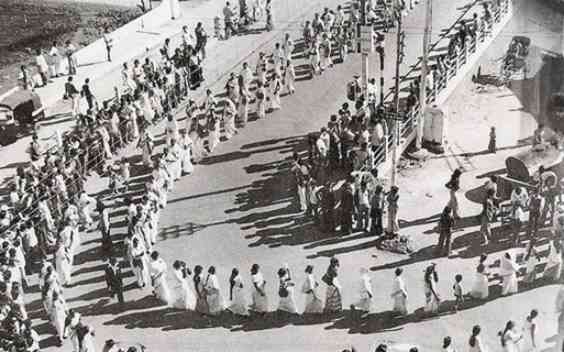

During the 1980s and 90s the RSS works actively on securing a foothold throughout the North-East. It sets up Vanvasi Kalyan Ashrams for the tribes. (The RSS’s initial term for tribal peoples, girijan, or hill folk, turned awkward once harijan stopped being used for dalit communities, since the two terms were twinned in usage. Vanvasi, or forest-dwellers, neatly sidesteps the problem of recognising adivasis as primeval inhabitants – a status the RSS reserves for “Aryans”.) The organisation faces resistance in Tripura where the CPI (M) is strong, but it becomes a major player in Arunachal Pradesh, which comes to acquire the highest concentration of Hindi speakers in the North-East. The RSS also reaches out to the xatradhikars or heads of Vaishnav monasteries in Assam, and begins to infiltrate the tea tribes. In a region where beef-eating is common, and Christian, Buddhist and a variety of non-Hindu animist faiths predominate, the RSS does not challenge local practices but exploits faultlines between communities to further its national agenda. For instance, in Meghalaya it targets “Bangladeshi” (Bengali-speaking Muslim) men who marry local girls and set themselves up in business. - 1983, February 18: At Nellie, 71 km from Guwahati, in fourteen villages, over two thousand Muslims, mostly children, women and old people, are massacred and their homes set on fire in a matter of hours. The attackers are local Axomiya Hindus and Tiwa tribesmen who use spears, sickles, and firearms on the victims. Hearing rumours of imminent violence, a delegation of Muslims had asked for police protection two days previously. The police did not act. Afterwards, 688 FIRs are registered but only 299 chargesheets are filed. No one is found guilty or punished. The Assam Internal Disturbances Commission, set up under T.P. Tewary, submits its report on the massacre in April 1984. The report is never made public. From now onwards, violence against Bengali-speaking Muslims becomes a recurring feature of the Axomiya movement.

- 1983: The Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunal) Act is passed by parliament. Rather than requiring an accused individual to prove s/he is not a foreigner, it shifts the burden of proof to an accuser and the police. Further, it lays down some clear terms, such as excluding pre-1971 migrants from having to prove their citizenship. It also specifies that the production of a ration card shall suffice to prove citizenship. Further, an accuser must live within a three-kilometre radius of the accused, a fee must be paid to lodge an accusation and an accuser may charge no more than ten people of being aliens. The IMDT Act is not long for this world, struck down by the Supreme Court in 2005 (see Part III: Assam Accord to the Present).