Following the February 7 Supreme Court judgement by justices L Nageswara Rao and Hemant Gupta, in a suit titled Mukesh Kumar vs The State of Uttarakhand, the future of reservations for the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes has been thrown into doubt.

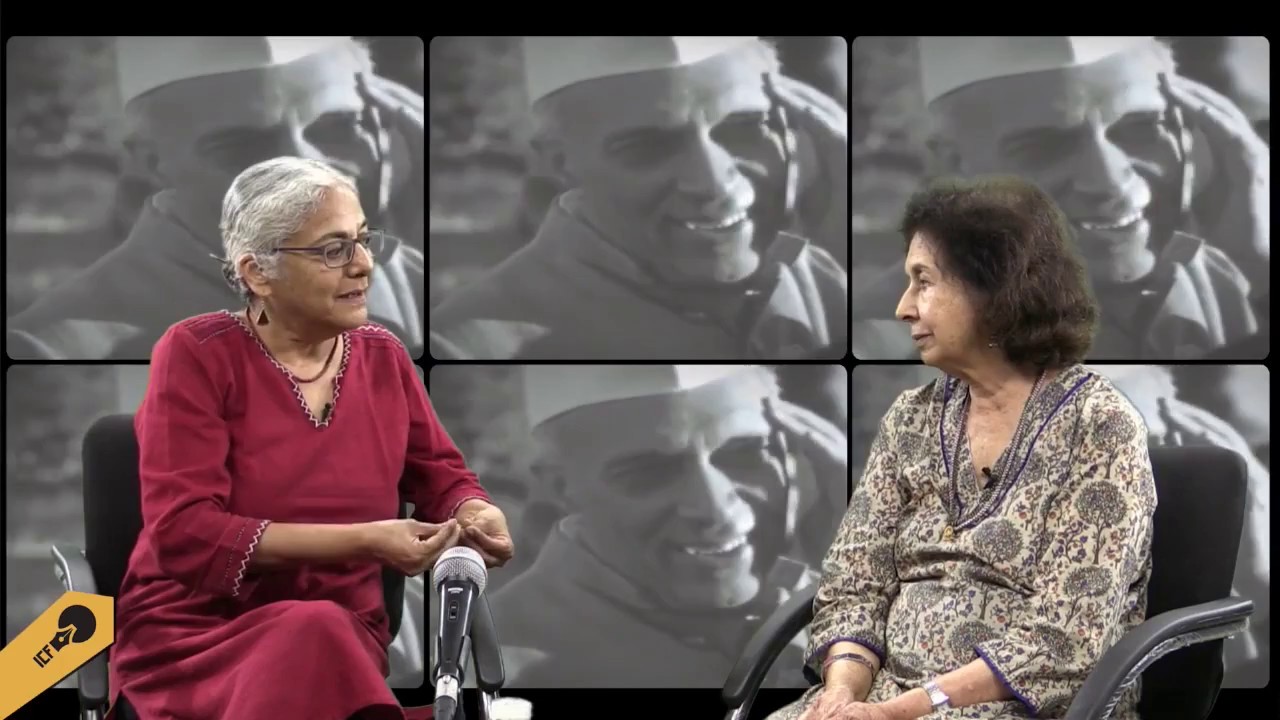

Looking for consistency in the Supreme Court’s position, Prof Faizan Mustafa explains the background of this case and examines the present judgement against various others given by the Supreme Court. What follows is an edited translation of his talk, from the Legal Awareness Web Series.

Before us today is another judgement on reservations from the Supreme Court. If you read the judgements on this issue given by various high courts and the Supreme Court you will see that they mostly favour ‘merit’ over reserved seats. Indeed the courts are on the whole against reservation and that is why they keep finding new means to control it. For instance the Supreme Court invented a 50 per cent rule to set an upper limit on reservations, in the Indra Sawhney vs Union of India case of 1992. The obvious import of the judgement was that in a society where 70 per cent of the people qualify as backward, 50 per cent of seats were set aside for them, with the other half going to the remaining 30 per cent of the people.

A year and a half back, the Supreme Court gave its judgement in the Jarnail Singh case (September 26, 2018), rejecting the idea of reservation in promotions. Earlier the same year the court diluted the Scheduled Castes and Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989; eventually, parliament intervened to overturn the judgement on the POA. The court has now upheld parliament’s move and recalled its own judgement. However, when the POA judgement arrived, on March 2, 2018, several newspapers were prompt in welcoming it. We have a similar situation today. In the Mukesh Kumar case, the present judgement against the Uttarakhand High Court has been welcomed with an editorial in the Times of India (February 10). I think the judgement needs to be examined in detail before we commit ourselves to a position.

The issue of reservations has been shrouded in myth for a long time. Some critics claim that reservations were intended for just the first ten years after the enactment of the Constitution. In fact, no such time limit was set for reservation in jobs. It was the system of reserved seats in parliament that was meant to last ten years, and has been extended regularly. We need to go into the genesis of reservations. I want to emphasise that any constitution is a sacred pledge. Whether in the form of Article 370 or of reservation, the pledge should ideally be honoured.

The Poona Pact of September 24, 1932, was concluded between the leaders of caste Hindus and the dalits [or, Depressed Classes, as the nomenclature went]. The British prime minister, Ramsay MacDonald had announced a Communal Award on August 4, 1932, under which the Depressed Classes were recognised as a separate electorate. At the Second Round Table Conference held earlier that year, Gandhi had declared himself amenable to separate electorates for Muslims but did not want those electorates extended to the Depressed Classes. [Ed. See A.G. Noorani’s article in Frontline, “Ambedkar, Gandhi and Jinnah” (June 12, 2015) here. Noorani records Gandhi’s failed attempt to reach a bargain with the Muslim delegates at the Conference. He offered them his support for separate electorates in exchange for their opposition to the demands of the Depressed Classes. He was turned down.] At the time, the Muslim delegates had refused to separate their demands from those of the Depressed Classes. After Gandhi’s fast unto death at the Yerawada Jail, the Poona Pact was reached, which increased the representation of the Depressed Classes, with concessions made to them for ten years: 18 per cent reservation in the central legislature and 147 seats in the states. Later, Ambedkar frequently called it blackmail and regretted the outcome. During the Constituent Assembly debates on Article 16 (equality of opportunity in public employment), Ambedkar pointed out that it was important to remember, in speaking of equality, that many people in our society remain unequal and require affirmative action for their uplift.

Let us turn to the facts behind the judgement of February 7, 2020. In 1994, the Uttar Pradesh Public Services (Reservation for Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes) Act came into effect. Section 3, clause 1 of the Act said that there would be reservation at the stage of direct recruitment into government service. The government would also issue an order dealing with reservation in the context of promotions and the order would prevail until it was modified.

Uttarakhand came into being in 2001 — during Vajpayee’s government at the centre — and the 1994 law was extended to the new state. On September 30, 2001, a change was made to the modalities of reservation: for Scheduled Castes it was brought down from 21 per cent to 19 per cent, the share of the Scheduled Tribes was raised from 2 per cent to 4 per cent, and the Other Backward Classes came down from 27 per cent to 14 per cent. Following this, a debate began on Section 3, clause 7 of the 1994 act: “If, on the date of commencement of this Act, reservation was in force under Government Orders for appointment to posts to be filled by promotion, such Government Orders shall continue to be applicable till they are modified or revoked.” The clause was challenged, and the matter duly went up to the Supreme Court. The Uttar Pradesh Power Corporation vs Rajesh Kumar was the title of the suit. The court declared Section 3(7) unconstitutional, adding that it contradicted the court’s judgement in the M. Nagaraj case of 2006.

Also Read: A New Assault on Reservations

Bear with me here. The technicalities of the law are important to understand if we want to know the rights and wrongs of the Supreme Court’s position. In the Nagaraj judgement, the Supreme Court had laid down three conditions to be met for the implementation of reservations: 1. There must be quantifiable data on “backwardness”, identifying who is backward and how backward in relation to others. 2. If a community is sought to be included within the ambit of reservations, there must be data demonstrating its present levels of representation in the jobs and posts where reservation is to be introduced. A case may be made for reservation if the community is found to be under-represented. 3. Reservation should be extended only after ascertaining that it would not negatively affect the efficiency of the concerned department.

In 2018, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court reviewed the Nagaraj judgement which had come under challenge. This bench declared that the first condition (listed above) would no longer apply, since a community brought into the SC-ST list by a presidential order has already been established as backward; no further study was required to confirm the fact. But the Supreme Court stood firm on the other two conditions it had laid down earlier — requiring proof of the inadequacy of a community’s representation, and the point about impact on efficiency. This five-judge bench included Dipak Misra, then chief justice of India, and it refused to refer the matter to a larger bench. The Nagaraj case is back before us. In the UP case I mentioned earlier — the power corporation one — a review petition (by Vinod Prakash Nautiyal) had been dismissed. It was settled that a committee would be formed to collect data on inadequate representation.

An important point to note: While it is well known that the Hindu right and the RSS have, shall we say, reservations about reservation, it was a Congress government in Uttarakhand that issued the circular of 2012 which was disputed and has now been upheld by the Supreme Court. A committee formed that year had stated that the representation of backward groups was inadequate, but the government’s circular of September 5, 2012, was issued despite the committee’s report; it effectively ended reservations.The chief minister of the day, Vijay Bahuguna, later joined the BJP and tried to overthrow the Harish Rawat government of the Congress, but that is another story. It was Bahuguna’s Congress government that declared all previous government orders on reservation void, and announced that government posts in Uttarakhand would be filled without reference to reservations for the SC-ST categories. A Mr Gyan Chand, then working as an assistant commissioner (civil) in the state tax department, moved court against the order. This time — April 1, 2019, with a BJP government in Uttarakhand — the court struck down the circular of September 5, 2012. The high court said that reservations are an enabling provision, not a right, and it was not necessary for the state government to collect data on representation or backwardness. The high court’s order was challenged as the state government asked for a review. The court modified its order, citing the Jarnail Singh case (of 2018, mentioned to you earlier). The state government was not required to collect data on backwardness, but adequacy of representation and impact on efficiency still had to be considered. This time, the BJP-led state government went to the Supreme Court. Mukul Rohatgi, arguing for the government, contended that reservations are not a fundamental right, the provision for them is an enabling one; thus, it is up to the state government to provide reservation or not.

Also Read: Faizan Mustafa : Is NPR really legal?

Let us turn to the broad points made in the Supreme Court’s judgement. The court has said that reservations are not a fundamental right. In a strictly technical sense, the court is correct: no article of the Constitution explicitly states that reservation is a fundamental right. However, we are living in strange times when the basic framework of the Constitution is under stress.

The Jammu and Kashmir Bar Association’s president was detained in August last year, under the Public Safety Act. On February 7, 2020, the challenge to his detention was dismissed by a single-judge bench of the J&K High Court. The judge stated that the law “prescribed no objective standard for preventive detention” and so “the court leaves the matter to the subjective satisfaction of the Executive”. A man was taken into preventive custody in 2019 on account of an incident that dated back to some ten years previously and the court simply washed its hands of the case, leaving it to “the subjective satisfaction of the executive”. This is reminiscent of the court that had stood with the government in the infamous ADM Jabalpur case (1976). A five-judge bench of the Supreme Court had stated that Article 21 — the right to life and personal liberty — stood suspended with the declaration of Emergency and, with it, the remedy of habeas corpus ceased to be available. The Supreme Court overruled this judgement with the privacy judgement (2017). Perhaps we are in for another wait of some years before the court concludes it was in the wrong.

Technically speaking, no article guarantees reservation in the manner that freedom of speech or religion is framed as a fundamental right; there is certainly no explicit right to reservation. Perhaps the court is right to say that it cannot direct the government to implement reservation, but nor is it instructing the government to collect data showing why it will not provide reservation. Consider the difference between the two halves of that sentence. The two-judge bench is saying that if the government chooses not to provide reservation there is no need for research or data to justify its decision. No need to discover if numbers on the ground correspond to shares in employment-representation. Such a study would be required only if the government wishes to provide reservation. The exercise of reservation is placed on a defensive footing, while the absence of reservation becomes an untroubling state of affairs.

At root, it may be a sound guiding principle for judges to say that in matters concerning government policy decisions, courts should generally uphold the position of the government. They should restrict themselves to checking if there is a material basis for the government’s decision, and if it emerges that there is such a basis, they should let the government get on with its work. Under this doctrine, the court accepts the legitimacy of judicial review, but maintains that it should be limited. But consider the case of Andhra Pradesh. In the matter of reservations for Muslims there, the high court did not apply this principle but placed the government’s decision under strict scrutiny before striking it down (2010). Again, in the matter of maratha reservations the Bombay High Court’s scrutiny was light. The court upheld virtually all the Maharashtra government’s decisions in this matter. Two separate backward class commissions had concluded that the marathas did not qualify as backward and the community had also been excluded from the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, but reservation for them was nevertheless upheld in court (2019).

Several judgements of the Supreme Court on reservation and promotion have been problematic — a vast topic which we’ll keep aside for another day. For now, I want to underline that reservation preceded Independence. In 1902, Chhatrapati Shahuji Maharaj introduced reserved seats in Kolhapur. In 1921, The King of Mysore acted on the Miller Committee’s report to introduce reservation in his state. In addition, “Scheduled Caste” became a working concept in 1935, with the Government of India Act. The Madras Presidency implemented reservation, reservation for brahmins. Champakam Dorairajan, a brahmin woman, went to court against these reservations. In the Constituent Assembly debates on Article 16(4), Ambedkar said that Article 16(1) — guaranteeing equality of opportunity — was insufficient by itself; our society includes people for whose equal enjoyment of rights we need to enforce affirmative action. Then, Article 46 of the Directive Principles of State Policy reads: “The State shall promote with special care the educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and in particular of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and shall protect them from social injustice and from all forms of exploitation.” Time and again, the Supreme Court has been a committed supporter of the Directive Principles, whether in the Sarla Mudgal case (1995), or Shah Bano (1985) or many others. Article 46, making specific reference to the SC-ST communities, establishes the protection of the interests of the weaker sections as a duty of the state. Article 335 states that the claims of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes shall be taken into account. Whether all this amounts to a fundamental right or not, the right to equality is certainly one.

Also Read: Sedition: Criminalising Dissent

There’s a narrow interpretation of equality, in purely formal terms, and a wider interpretation that seeks substantive equality. Till the seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court gave its judgement in the N.M. Thomas case (1975), the court had held that Article 16(4) was an enabling provision and an exception to the concept of equality. In the Thomas case, the court decided that 16(4) was part of substantive equality, not an exception anymore but an extension of the right to equal opportunity. Thus, reservations emerged as part of the right to equality — a fundamental right.

Formal equality is about treating all people alike and distributing resources equally among them. However, someone at a disadvantage needs support to a greater extent than someone who is comfortably placed. Substantive equality recognises this qualitative difference. Unlike formal equality, it classifies the prospective beneficiaries on the basis of their need and the likely scope of benefit to them. It takes into account people’s location along an axis of advantage and disadvantage. If substantive equality is part of our right to equality, it is untenable to insist that reservation is not a right. While a limited interpretation of fundamental rights may be technically correct, it will not make for sound policy. There are numerous cases where the Supreme Court directs states on the matter of representation. The National Legal Services Authority or NALSA judgement (2014) found transgender people unerrepresented and directions were issued to redress the lack. In the Vishaka case (1997), no law existed in the book but the court cited international conventions to direct lawmakers to frame laws protecting the dignity of women in the workplace.

The present judgement, in my opinion, is problematic and should be examined by a larger bench of the Supreme Court. The Nagaraj judgement should also be referred to a larger bench. As for the issue of reservations and efficiency, we will return to it another time.