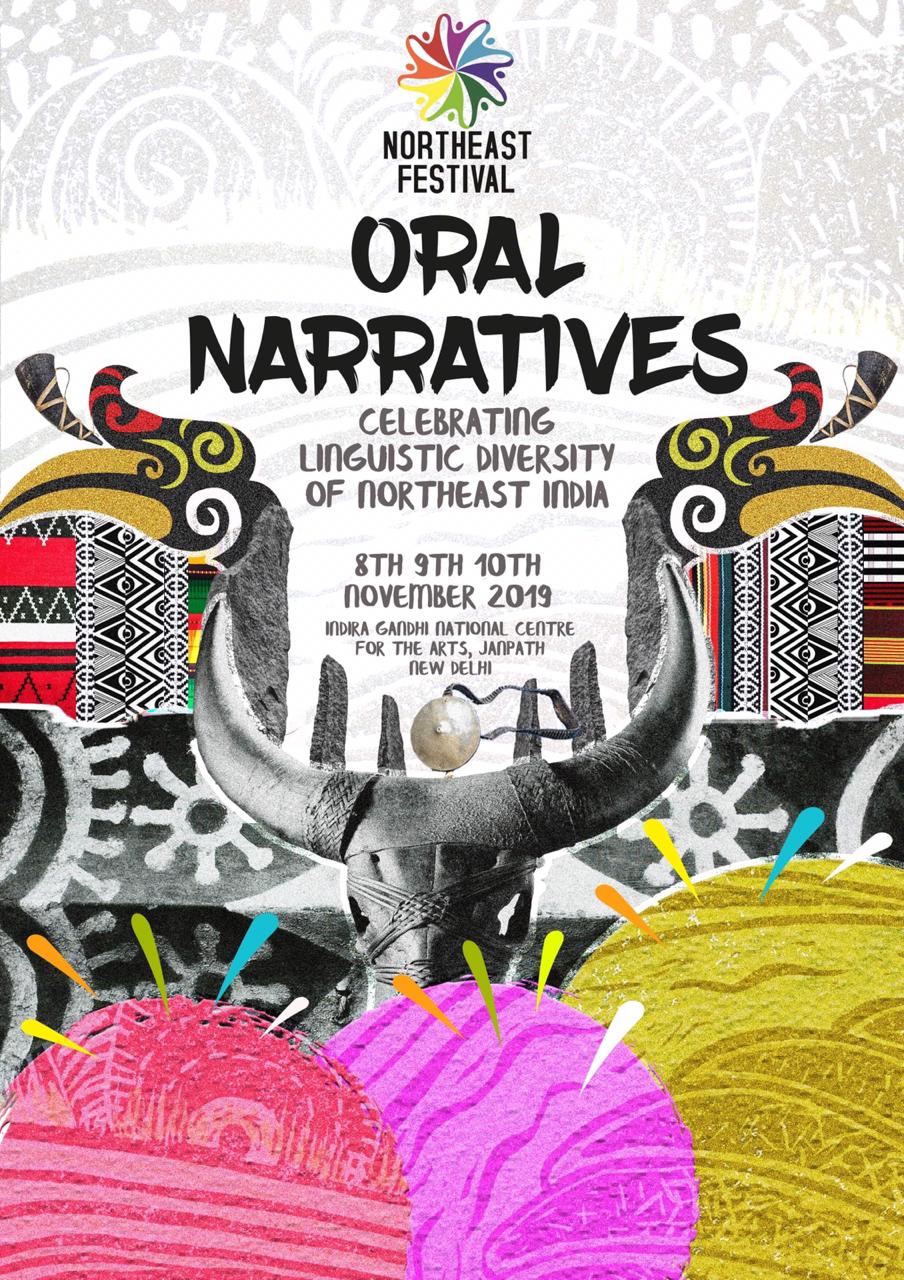

A timely organised panel discussion, at the 7th edition of the North East Festival in New Delhi last week, talked about the status of indigenous languages of the North East of India, an intensely debated topic in contemporary times. Titled “Extinction of Indigenous Language and Cultural Change: Views from North East India” and conducted at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) lawns, the panel included academicians Dr. Usham Rojio, Dr. Prachee Dewri and Dr. Lianboi Vaiphei.

The discussion commenced with moderator Dr. Lianboi Vaiphei, faculty at Indraprastha College, raising questions about the “reasons behind the loss of indigenous languages in the region”. Dr. Usham Rojio, academic counselor at IGNOU, refuted the idea that “when a language dies, a culture dies” and argued that the death of a way of life leads to the disappearance of a certain knowledge system and along with it dies a language, owing to the cultural hegemony of a dominant group. “Cultural hegemony creates binary oppositions such as the distinction between folk and classic, where folk is looked down upon while the ‘classical’ is preserved,” Dr. Rojio added.

Also read : Singing opera in Khasi: The Shillong Chamber Choir

He opined that this process was similar to the phenomenon of “Sanskritisation” in mainland India – a process by which people from the “lower” castes are forced to seek upward mobility by emulating the socio-religious practices of the “upper” or dominant caste groups. People in the North East, in his opinion, are giving up their “indigenous” cultural practices to seek upward mobility in society through Brahmanisation (in the cases of Assam and Manipur) and Westernisation (Meghalaya, Nagaland and Mizoram), leading to the gradual extinction of their own tribal languages.

Dr. Prachee Dewri, a faculty at Hansraj College, said “migration too leads to loss of language and cultural practices”, citing a case study based on the Deori tribe. Deori is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken by the Deori tribe in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. A part of the Deori community inhabiting the Sadiya region was forced to move to the Assam valley years back. Historical evidence highlights that during the migration, a Deori clan called “Patorgaya” lost their way. Speculations of them having merged with another community hints at how migration also leads to disappearance of tribes but also to the birth of new ones. The Moamoria Rebellion (1769–1805) in Assam also caused another wave of migration among the Deori people to other parts of Assam. Many of them adopted new practices such as learning the Assamese language and practicing dry paddy cultivation to suit the new landscape, she added.

Borrowing from Kenyan writer and academic Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s works, Dr. Rojio said that the cultural practices of the North East should be viewed as “orature” — a complete system in itself for a society to exist, not just in the form “external manifestations” like performing arts but one that also includes the “interiority” of the culture, in the form of knowledge systems and “core values of the community”.

Referring to Garo film My name is Eeooow which tells the story of the three sons of a mother with the same name, but distinguished according to three different tonal vibrations of sounds in the names, Dr. Rojio stated that accommodating such minute details is a complex task today. He spoke how rapid urbanisation has depleted “orature”. In the Northeast, each orature developed as a system of knowledge owing to its unique landscape. “Development” induced displacement not only causes change in landscape but also results in loss of meanings associated with the landscape. He added that folk performances in metropolitan cities often end up exoticising the art forms.

Also read: Ho Delo: When Rock meets Folk melody

Dr. Dewri spoke on the “cognitive dissonance” experienced by the Deori tribe children at school due to the Anglicised representations of families in textbooks, making it difficult to relate to their own family. She said that “real efforts” to preserve languages should come from within communities, for “instructions from above” on cultural preservation will not be very helpful. Use of mother tongues as the medium of instruction as well as the development of school curricula based on realistic representations of the societies the children belong to are some of the measures that could help.

Dr. Lianboi Vaiphei wrapped up the discussion by saying how “English was not the only threat to tribal languages”. Adding to Dr. Rojio’s argument, she said how the use of the languages of “dominant” classes of a particular region could also discreetly kill the “smaller” tribal dialects. The use of Meitei as the lingua-franca by tribal community in Manipur, for instance. She warned that standardization of tribal languages could lead to a loss in the “real essence” of tribal languages.