Image courtesy: Yogesh Maitreya

Image courtesy: Yogesh Maitreya

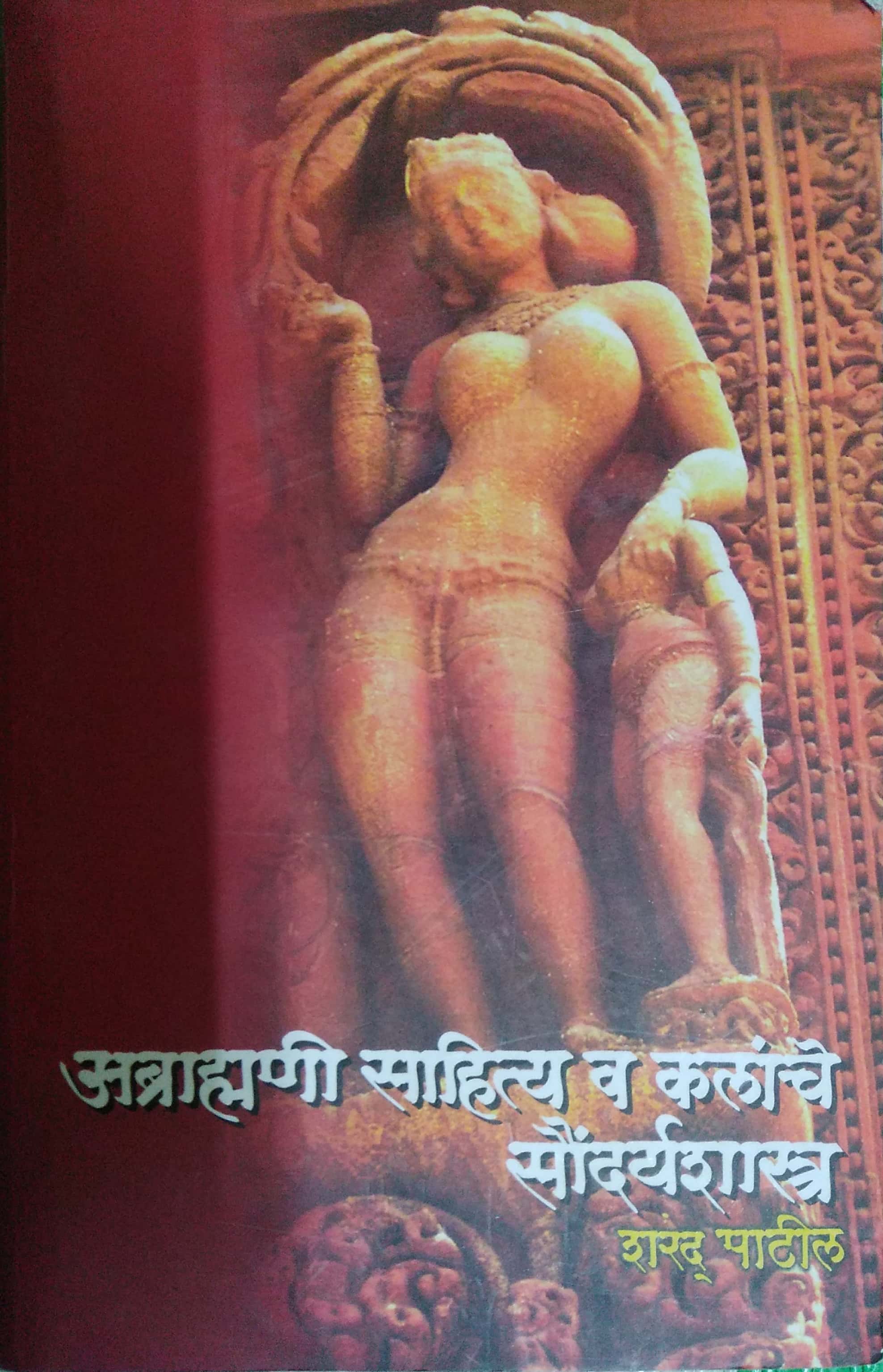

Sharad Patil’s 1988 work, Abrahmani Sahityache Saundaryashastra (Aesthetics of Non-brahmanical Literature), is a striking commentary on the philosophy of literature. Its second edition was published in 2017 as Abrahmani Sahityache aani Kalanche Saundaryashashtra (Aesthetics of Non-Brahmanical Literature and Art). Metaphorically speaking, it is a key to many puzzles that haunt the field of literature in India. As a meticulous dissection of brahminical hegemony in the field of literature and art, the book theorises—for the first time using political axioms—that caste is at the root of production of art and literature in India.

Patil argues that to understand the politics of literature and art in India, one must never lose sight of the caste of an artist. Abrahmani Sahityache’s second edition published in 2017 enlarged the scope of the book to dissect the aesthetics of non-brahminical art, apart from the literature.

Image courtesy: Yogesh Maitreya

Image courtesy: Yogesh Maitreya

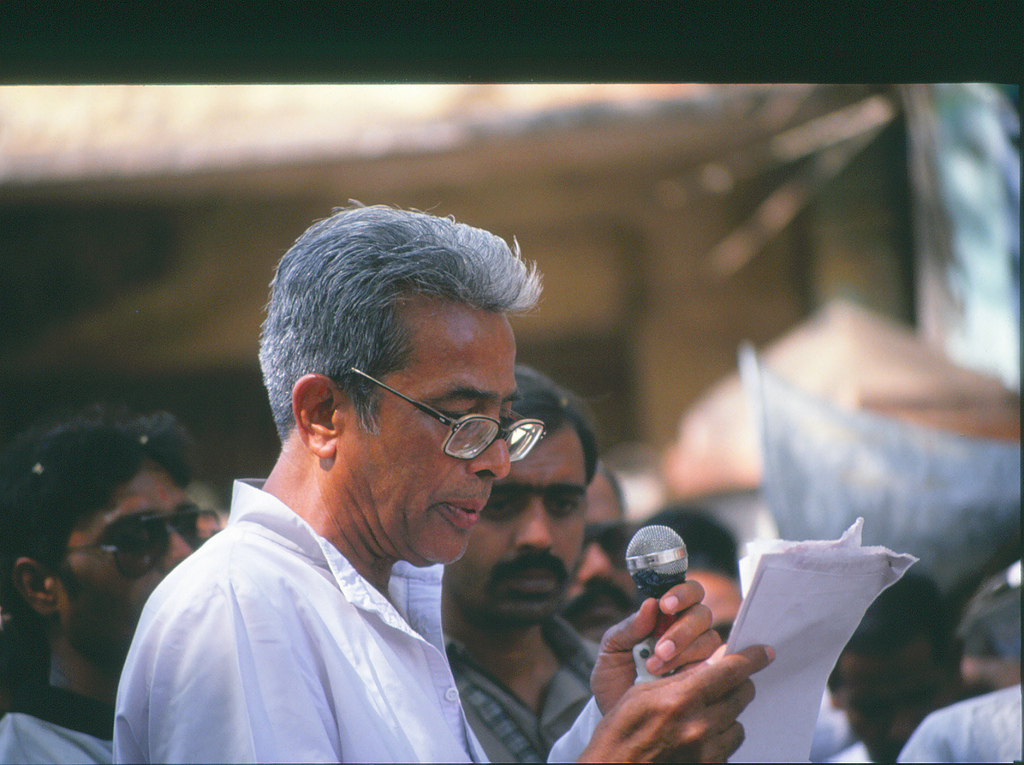

Patil was a brilliant and incisive philosopher, and a theorist and scholar of Panini Sanskrit. He founded the Marx-Phule-Ambedkar school of thought as a rebellion against brahmins and brahminism within the Marxist fold. He also started the Satyashodhak Communist Party based on a synthesis of Phule thought, Marxism and Ambedkarism.

Casteism in the discipline of translation in India has limited and confined Abrahmani Sahityache’s breadth and capacity. Yet the book still speaks for itself. It makes a remarkable proposition with respect to the caste location of the writer, his work and his ideological affiliation. Patil establishes a framework for literary agency in which an artist/writer’s instrumentality is socio-ideological: informed by their caste, works and ideological positions.

Patil calls Fakira the “best” of all novels by Annabhau Sathe, the greatest among Maharashtrian dalit writers and communist (later Ambedkarite) social reformer. He says, “The responsibility imposed on this communist Mang writer is to show that the cactus-like boundary between the colonies of the untouchable Mahar-Mangs and savarna Kulkarni-Patils in Maharashtra’s villages was that of the class system and not of the caste system.”

Patil acknowledges that in Fakira’s time, 1959, caste was certainly much stronger than class in the villages of Maharashtra.

He says:

But, since it was imposed on the mind of Annabhau that the suffering of [an] untouchable peasant is equal to [the] suffering of [a] touchable peasant in terms of their class; unsurprisingly, his talent was unable to trace the source of caste-class sufferings.1

This critique is not just a breakthrough from the traditional and defunct method of understanding literature. Patil’s argument here is far more comprehensive, coming from a brilliant coalescence of the thoughts of Marx, Phule and Ambedkar. That is why his book is brimming with radical and convincing propositions. His framework of Marxism, phenomenology and Ambedkar’s vision of annihilation of caste(s) enrich the craft and tradition of literary criticism.

Patil’s most original argument relates to the causal link between the 1956 mass conversions to Buddhism in Maharashtra and the emergence of dalit literature. The conversions led to the creation of a body of dalit literature, for they created a reader and an anti-caste, non-brahminical literary conscience at a large scale.

The dialectical link Patil drew between the emergence and development of dalit literature and the 1956 event was a new and fresh premise from which to understand dalit literature. He traces in detail the correlation between literary consciousness among the dalits and their conversion, in which they were following Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar’s lead at the time. From here, he elaborates the historical links between the dominant religion—brahmins/brahminism—and the religion which has a history of fighting the caste system: Buddhism.

Patil said that the oppressive caste system needs to be broken in order to reach enlightenment. That would mark the beginning of a society based on rationality and logic, wisdom and compassion. If the body of dalit literature is studied critically and honestly, these principles surely stand out as essential guiding principles in its formation.

Further, Patil argues that the study of society based on materialistic perceptions, and from the viewpoint of “impermanence”, can only determine whether its religion, politics, philosophy and art are a reflection of its economic structures, a reaction to it or its symbols, or all of these.

Although scholars, Lenin included, considered Marx’s scientific knowledge ‘reflectionist’, yet, the process of forming concepts that are triggered by sensory experiences is certainly not reflectionism. Not only consciousness but the subconscious, too, participates in the process of formation of concepts. This is proven by Freud’s psychoanalytics and Frezer’s Abolitionism.

He says:

Rejecting the model of historical materialism due to some of its inevitable limitations is like rejecting a grain of rice because of its husk and bran, as Charwak said.2

What Patil means is that historical materialism is important, for it helps understand how society revolves around material change. At the same time, he suggests that some people go beyond this and make other worlds possible. Marxism, in his view, had proved incapable of resolving conflicts in Indian society but he makes sure to develop, over the years, a theoretical framework that makes better sense of the world if not absolute sense of it. Abrahmani Sahityache, from the Marx-Phule-Ambedkar school of thought, provides this wider theoretical framework to understand the production of literature and art in India and, of course, its politics.

Using the historical dialectical approach, Patil’s Abrahmani Sahityache offers a much-needed understanding of the historical premises on which brahminical individuals have appropriated the arts and literature of dalit-bahujan masses.

He argues:

For, the task of changing a good into a commodity that they [Brahmins] would find desirable had already been made by the Shudra-Untouchables and all the toiling castes.3

This opens a Pandora’s Box of truths that testify to the ongoing crises in the social, political and cultural life of the country. It summarises the history of appropriation of the labour, literature and arts of dalit-bahujan masses. They who were once creators of artefacts now find that their names have been erased from these fields.

Patil’s other important argument is on the role of gender. He imagines an equality in which—surprisingly—he convincingly refutes Marx and Engels propositions.

He says:

Since it had become impossible for Marx and Engels to accept that antagonism could have arrived in human society through sexual inequality, they have accepted the Utopia of primitive communism and made it impossible for today’s Marxists to bring about socialism.4

Being a scholar of Panini Sanskrit, Patil was equipped to decipher the meanings of texts that many Indian philosophers and writers could not. Not just in Abrahmani Sahityache, in other works as well, he methodologically develops the Marx-Phule-Ambedkar analytical framework. This, he uses to construct fresh perspectives that illustrate the journey of a literary process from life to the artefact.

Abrahmani Sahityache Saundaryashastra offers what most books over the last few decades have failed to offer on literature and art in India. The proposition that one must never lose sight of the caste of an artist when examining the politics of his works may sound too radical, but read it, read his earlier works, and Indian literature and art will never be the same again.

Notes:

1Patil, Sharad, Abrahmani Sahityache aani Kalanche Saundaryashashtra, 2017, p.60.

2Ibid., p.86.

3Ibid., p.141.

4Ibid., p.243.

Read more:

Raja Dhale: A Renaissance Figure in Dalit Literature and Art

दलित पैंथर: दलित अत्याचार के ख़िलाफ़ साझा संघर्ष

Sharankumar Limbale: “Literature that was restricted to a class or a group is now expanding”