Image courtesy Indian Express

Image courtesy Indian Express

If there is one man who deserves to be called a renaissance figure in dalit literature and art, it is Raja Dhale. Many may have heard of him only recently, when he passed away in July, 2019. Dhale was a remarkable poet; an occasional but refined translator; a fiery yet incisive critic of the subject at hand; a radical Buddhist philosopher; and a ruthless advocate of ethical politics. But most people know him as a co-founder of the Dalit Panthers, formed in 1972. They also know him as the author of “Kala Swatantrya Din” (Black Independence Day, 1972), the article that sent shivers down the spine of the brahminical literary circle in Maharashtra. But Dhale needs to be remembered for much more.

JV Pawar, eminent historian and co-founder of the Dalit Panthers, says: “If Dhale had not been at the forefront when dalit literature emerged, if he had not stood there with a naked sword in his hand, dalit literature would have been killed in its infancy. Even ‘experts’ on dalit literature agree on this.”1 Dhale’s collected works were compiled for the first time by JV Pawar; and in 1990, on Dhale’s 50th birthday, the collection was published in a book entitled Astitwachya Resha (The Lines of Existence).2 This significant book provides insights into Dhale’s meticulous understanding of various subjects, and introduces us to the many unexplored aspects of his personality—the writer, the artist, the literary theorist and the political visionary.

Literary renaissance has one crucial requirement. Old literary values need to be refuted; and new values—that connect to contemporary society and advocate justice in social life, have to be vehemently propagated. For this to happen, an understanding of the relationship between society and literature is essential. Raja Dhale not only had this understanding; he also had the vision to develop it.

Just as “literature is a part of our personality,” says Dhale, “it is part of our existence. This means (that) as literature shapes our existence, our existence shapes our literature.” Dhale captured the objective of literature at the theoretical level. But he did more. He developed the objective into a literary framework to resolve the tussle between Marxism and Ambedkarism. He spoke of this as early as 1976 in a speech delivered at a convention of dalit literature. This speech also marked the arrival of revivalist understanding of dalit literatures, inspired by the thoughts, teachings and literary vision of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar. Dhale’s speech shed light on literary aspects which had, till then, been matters of confusion and conflict in Indian literary spheres:

The concept of ‘Marxist literature’ originated from a theoretical understanding of society. But the concept of dalit literature originated directly from lived experience.

Today there are writings which can be said to be inspired by Marxian thought. But there is nothing that can be described as Marxist literature. Because of this, literature inspired by Marxian thought attempts to seize the field of ‘dalit literature’. Therefore, dalit literature should be called the literature of Ambedkar Pranalee (Ambedkarite ideology).

Till now, our literature has been that of Ambedkari (Ambedkarite) ideology. Because dalit literature emerges from life itself, it acquires social significance – which manifests as dalit social consciousness. This social consciousness of dalit life is shaped by Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar and his battles. Hence the social significance of dalit literature, is Ambedkari.

The vision of dalit literature is infused with its social consciousness – this is why dalit literature acquires social significance. But ‘Marxist literature’ has neither social consciousness nor significance; it has a theoretical significance. Just as its origin is theory, its eventual form too is theoretical, not social. The names Marxist literature goes by underline this. ‘Progressive literature’, for example: which social group does this literature refer to? Where exactly does it lead? Towards the social or the theoretical? Another example is ‘parallel literature’. The term does not clarify which social group and which social consciousness it is ‘parallel to’.

When we call ourselves litterateurs of Ambedkari ideology, and when we describe our literature as the literature of Ambedkari ideology, our objective of social revolution becomes clear. Likewise, our ‘place of work’ is also clear; it is the dalit community…

A skillful artisan gives shape to his artefacts, stroke after stroke, with persistence and patience. Like that artisan, Dhale’s meticulous study of literature and his understanding of theories of art and aesthetics shaped the discourse of dalit literature — which he preferred to call the literature of Ambedkar ideology — and the dimensions of its theory. Logic was never absent from his words– be whether he was writing his literary essays, articles, stories or his few but significant poems. For example, in his poem “Eka Panther Che Manogat”, he says:

Each man is the last one. If he sees that clearly,

why should he not fight each battle

as if it is the last one

I don’t understand it — because the end is decided.

Either the battle will come to an end

Or we will die.

If death is certain, why shouldn’t

the battle for equality be certain?

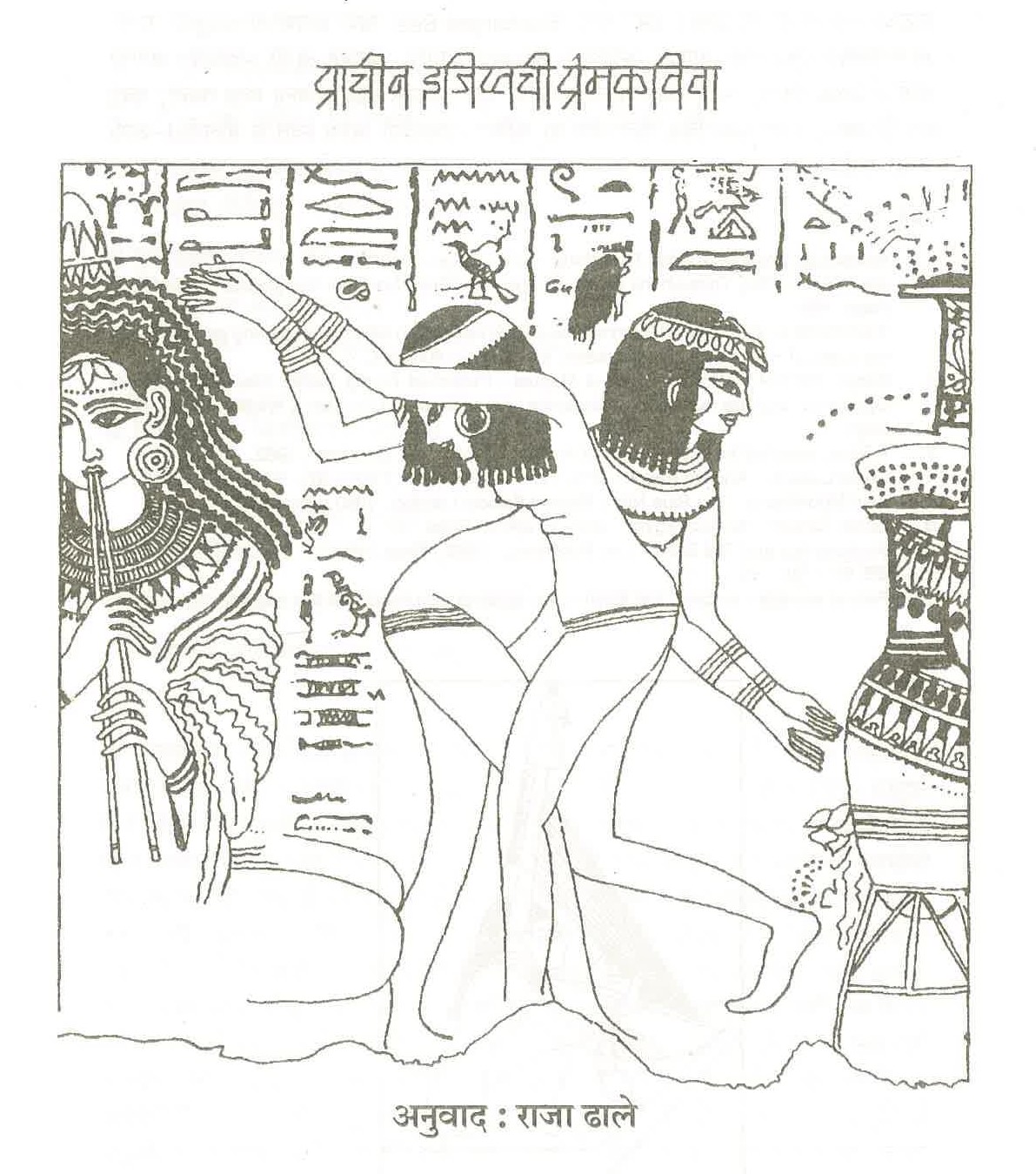

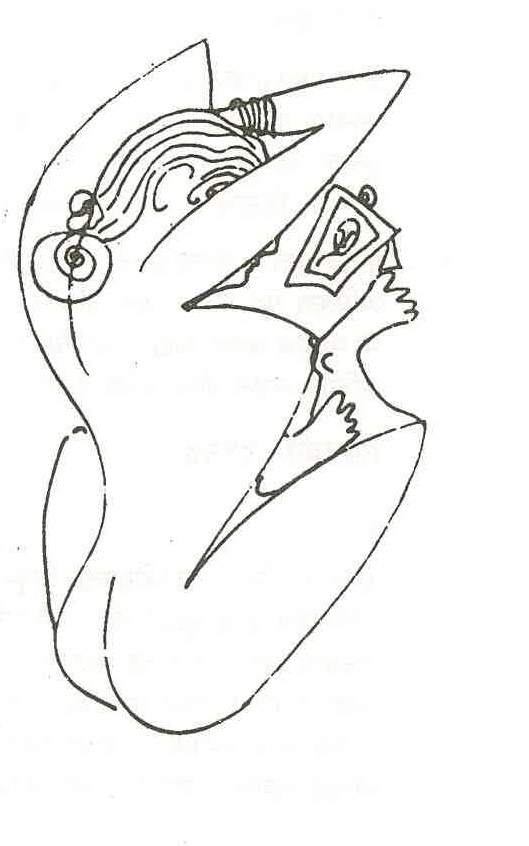

As part of social movements, Dhale’s words and actions were directed by his commitment to truth; justice; and the creation of a casteless society, whether in the realm of the imagination or in the real world. His life showed that he never bowed down before power. His literary and artistic talents gained strength from his unique imagination, which, in turn, was fed by Ambedkar’s thoughts and vision. This is why he found his reference in social history, the history of his community, and in the vision of Ambedkar, rather than foreign theories on art, literature and movements. His contributions to literature and art are unparalleled in the legacy of dalit literature. He wrote short stories, literary essays, critical reviews, songs for adults and children, and introductions to books. What he chose to translate is also telling: he translated Zen short stories, Egyptian poems, and poems by African American poets such as Langston Hughes, Samuel Allen and Robert Hayden into Marathi. As for his art, its idea of beauty is not sensual, but charged with sense; with sensibility. His illustrations reveal an artistic sensibility that suggests future directions for the anti-caste struggle. They also indicate why the appreciation of beauty requires the creation of a just and equal world.

Notes:

1 All translations are by Yogesh Maitreya.

2 Pranali Prakashan, Mumbai, 1990.

Read more:

Remembering Raja Dhale: How the Dalit Panthers Planned to Burn Holy Books

दलित पैंथर: दलित अत्याचार के ख़िलाफ़ साझा संघर्ष

Sharankumar Limbale: “Literature that was restricted to a class or a group is now expanding”

Strike a Blow to Change the World