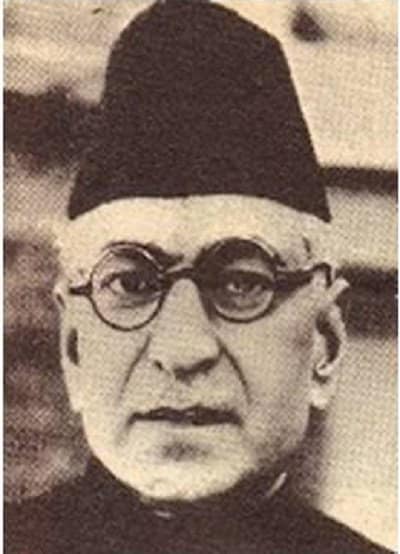

Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew was a barrister, politician and a Nationalist Muslim leader who fought fervently for India’s independence. But very few recall this giant leader from Punjab, who led the Hindustan Naujawan Sabha in the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, countered the Shuddhi programme launched by Arya Samaj, and opposed the Partition of India with determination. Though when writer and activist Anis Kidwai met him, he was no longer that person.

The following is an essay by Anis Kidwai on her encounters with Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew in his final days. The essay has been translated by Ayesha Kidwai who says,”[The essay] comes with the fervent hope that we should never lose like this ever again, and that the memories of that extraordinary generation will serve to inspire and caution.”

On 15 May 1973, an article on Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew, written by Gurmikh Singh Musafir appeared in the weekly, Al-Jamiat. I was both surprised and happy. Surprised because after all these years, a long-forgotten commander of the ranks of warriors for our freedom had been resurrected. And happiness because there were still people who could recall Dr. Kitchlew’s name with love. The fact is that no-one who writes the history of the Punjab can afford to disregard his name, even though in the last phase of his life, he had been cast aside just like a fly fished out from a bowl of milk.

For a few years, I too had the honour of his acquaintance, even though it was at a time of his greatest decline and when I was at my most defeated and alienated. Perhaps this was the reason why I saw only a little, understood less, and didn’t become very close to him. But perhaps it is nevertheless possible that a picture of him can be completed weaving together incidents and circumstances of his life, so truthfulness demands that whatever one saw, one puts down on paper.

Call it infirmities of memory or the effect of the tumultuous, disastrous times, I cannot simply recall whether Dr. Kitchlew ever came to Delhi before 1947. It was that December or January that I met him on the dining table. Seated on a table right next to Rafi sahab’s was this old politician, absolutely silent. Whenever Rafi bhai made some comment directed at him, he would have to cover one ear with his hand and use the other to bend the other ear, to try to reply to what was said. That great hero of Jallianwala Bagh, our honoured guest, was solitary, all alone, on our table.

His homeland was Amritsar, but looted and expelled from there, he had made it to Lahore — his wife and children were all there then. From his arrival on, he tried to save the lives of many Hindus and Sikhs and to arrange for their safe transport to India from Pakistan. This was no easy task, and on one occasion, he was surrounded by a violent angry mob and was mercilessly beaten. One ear-drum was shattered. Then his house was gheraoed, and although his family and friends managed to foil the attempt to murder him, but it became impossible for him to stay on in Lahore even for a single day. Mridula Sarabhai somehow managed to rescue him and bring him to India.

Just as in Lahore, where he was without protector or aide, he was not amongst friends in Amritsar, and religious Hindustan was certainly not ready for his tolerance and acceptance. He had no home anymore, and no means of income. He was not a citizen of any country, and not connected to any political party. Although he had countless friends in India, but in those days, there were just three who he was in touch with — Gandhiji, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Rafi sahab.

Gandhiji was martyred, Rafi sahab was his host, and Jawaharlal was his protector. The Congress was angry with him because he had unfurled the pennant of the Tabligh and Tanzeem movement (a movement to organise Muslims in the propagation of Islam and against the Shuddhi and Sangathan Programme organised by the Arya Samaj). Muslim Leaguers thought him the greatest enemy of Pakistan. That left the Akalis, who when they adopted him as their leader ensured that he was exiled from the Islamic brotherhood forever. And now, his entire wealth and property had been wrested by Hindus and Sikhs; he was no one’s leader any more, even though all admired his sincerity, amiability, bravery, affection, and humanity.

His injuries and lost hearing were treated, but the wounds in the heart were not to heal. In absolute silence, he would only occasionally emerge from his room. At the breakfast table, he ate sparingly, and then silently picking up a few newspapers and magazines, go back to his room to lie down.

Dr. Salimuzzaman, along with several other panaahguziins, was also staying in that room. but even though the two were in close proximity almost all the time, no words passed between them. One day, he remarked to me, “I must tell you Anis, that I am exceedingly disappointed on meeting this great Leader of the Punjab. Whatever I ask him, he does not give a satisfactory response. Mostly, the reply is noncommittal prevarication. So much praise for his intelligence and oratory I had heard, but it seems to me now that there is nothing in him at all. His fame seems all for naught.”

This was true. Doctor sahab was stupefied, and all desire to speak to anyone on any topic had indeed deserted him. Besides, why would he want to engage in conversation with the younger brother of the greatest votary of Pakistan, Chaudhury Khaliquzamman?

Very soon, Doctor sahab could be given a room of his own. soon it came to be thronged by a number of young men and women, sons and daughters of his friends. Mostly, they were the children of his Sikh friends, although I think the parents were hardly seen

Since all this was a long time ago, I don’t clearly recall, but once there was some discussion about Punjab, and Dr. Kitchlew made some soft intervention. Whatever it was, Rafi Sahab asked, “But doctor sahab, you were also a leader of the Sikhs! In fact it was you who had organised them.”

With great sorrow, Dr. Kitchlew confirmed his role, but he also said that his objective was to integrate different sections, and to unite them. “But what can one do, when it all had the opposite result?”

Soon, a host of people started streaming into meet him. Some of them came seeking his advice, others to narrate their ordeals and tales of woe. But not one would ask him to come to live in Jalandhar, or Amritsar or Ludhiana. Neither Musafir sahab nor Sachar sahab ever made this proposition, and neither did Gopi Chand Bhargava. Abdul Ghani Dar and Yasin Khan were themselves homeless. And it was against Dr. Kitchlew’s principles to demand that he be compensated for the loss of his property.

In 1948-49 when the rehabilitation of refugees began, the camps were dissolved, and large neighbourhoods started to be repopulated. In order to promote harmony and peace, the need for Muslim and non-Muslim volunteers came to be felt. In response to Shafiq-ur-Rahman’s need for eight or nine Muslim volunteers to run schools and centres in Delhi’s neighbourhood (under his scheme “Taalim, Tarbiyat-o-Taraqqi”), Dr. Kitchlew gathered together a group of young educated poor Muslims. These were mature and responsible young people, who had been under his instruction since for many months. But they themselves were refugees, and it was impossible for them to devote many months in relief and rehabilitation work without any remuneration. Very soon, all of them had to become engrossed in the search for employment and further education.

In our programme to save Delhi’s mixed neighbourhoods — Pahari Dhiraj, Kassabpura, Bare Hindu Rao, etc — from another round of communal strife, Dr. Kitchlew’s support too was enlisted. The first time he went to Kassabpura, the very mention of his name caused a flutter of speculation in the people gathered. One gentleman even went to the extent of asking, “Is he really a Muslim? We had heard that he was a Sikh.” We learnt then that this propaganda was one of the several canards that the Muslim League had spread about him — that he had converted to the Sikh religion.

There was also much debate about his departure from the Punjab and arrival in Delhi — what meaning did his leaving the ‘hallowed land’ of Pakistan to come to settle here have? This took some time to comprehend. And then his speech satisfied all his listeners. The passion and the oratory was rejuvenated, and could express its grief and sorrow at this destruction of humans and humanity. Everyone came to acknowledge the felt need for peace and unity. And when the speech ended, he was accorded the greatest honour and veneration, and was bidden farewell with the greatest respect.

But after deploying his personality in two or four more neighbourhood and village conventions, we all came to feel that our demand was an imposition. Because the truth was, there was no longer either that ‘flower of lyric’ or the ‘veil of musical notes’; all that remained was ‘the utterance of mine own defeat’. If we were to play this broken instrument again, it would fall silent forever.

Rafi sahab tried to arrange his wife and children to be brought to India. The first to arrive were his daughters, and Dr. Kitchlew remarked that this means that Apa will also arrive soon, as soon as we get a house. We thought he was speaking of his elder sister’s arrival — he used to mention her often and in fact, spoke mainly of her.

Soon after, people from a Delhi mohalla proposed a scheme by which a house could be extracted from the Custodian of Evacuee Property’s clutches — if Dr. Kitchlew were to get this house allotted to himself, we would be happy, and so would be our god. But Dr. sahab said, “My children are not used to living in neighbourhoods with narrow lanes, they will not be able to manage.” None of us were enamoured of this reply, but we didn’t know as yet about the many houses and vast amounts of property he had left behind in the Punjab.

Finally, ‘Apa’ arrived, a woman with a typical Punjabi face. Young girls and boys, all of them highly educated, also arrived. Everyone was khadi-clad, so much so that even Apa’s dupatta was made of khaddar. Apa turned out to be Dr. Kitchlew’s wife and the mother of all these children. Surrounded by her six to seven grown up children, innocent Sifat Apa was a great literary enthusiast and was blessed with an extraordinary forbearance and fortitude. Not once did she ever break down and narrate the tale of her family’s destruction. Let alone ruing the home and household that she had lost, she never even uttered an anxious word about how the family would manage, now that age and circumstance had rendered Dr. Kitchlew unfit to continue his career as a barrister.

That incomparable woman, who was her husband’s sincere wife and affectionate mother to her children, had perhaps made it her calling to be always content. Never did I hear from her words of complaints about friends or reproach for enemies, and not even words of flattery about benefactors.

After a life in one room for about two years, Dr. Kitchlew was allotted a house near Pandit Nehru’s Teen Murti residence. Pandit Nehru had it done, because Dr. Kitchlew said he couldn’t bear to live too far from him and not see him regularly. While he was with us though, Dr. Kitchlew hardly met Jawaharlalji personally. The only person he talked to was Rafi sahab, and it was through him that messages to Jawaharlalji were conveyed. It was because he didn’t have any means of transport, and it was an offence to his self-respect to ask anyone of this favour. Asa consequence, he never even occasionally fulfilled his desire to see Jawahar and hardly visited anyone at all. His friends and companions had all averted their faces, and the Congressis had all forgotten that he was once our leader.

Apa was even more independent than Dr. Kitchlew was, although she would always make it a point to attend literary meetings and religious gatherings in Delhi. But she always came and returned by bus. Often, meetings went on too late, but she would not countenance the favour of a lift from someone with a car. Only rarely would she succumb to insistent pleas of a close friend who couldn’t bear to see the hardship she had to bear.

After they moved, we met less frequently. But whenever we did, our meetings were pleasant, full of light-hearted laughter. At home, Apa lived surrounded by books and newspapers, and was mostly to be found either cooking in the kitchen, or in washing clothes, or in cleaning the house. One day, Apa telephoned to say, “we have invited only a few people — it’s our eldest daughter’s wedding today. you must come.” We went there to find a gathering of twenty-five to thirty people. Arrangements had been made for a small little party, chairs had been set out in the courtyard, and the bride, wearing a red dupatta over light clothes, was seated amongst the guests next to her bridegroom. The nikaah was performed, everyone congratulated the couple, and after tea and refreshments were served, the guests departed. When we reached back home, Rafi sahab remarked. “What a lovely, simple wedding Doctor sahab arranged! This is how it should be.” He was always a great believer in simple marriages.

The truth was also that in Doctor sahab’s straitened circumstances, what more could have been done anyway? I do not know how he managed to make ends meet, how he arranged the marriages of his other children, because his two sons were still studying and not employed. Yet no one else outside the house, save for his two friends, ever got wind of the difficulties he faced.

And when he was ill, it was Jawaharlalji kept track of his needs. Every visitor to his sick-bed would be greeted with a smile, as he called out to Apa to come and see who had come to visit him. But the fact was that even on his death-bed, he found no peace. Once I asked him, But if you were to actually just go to Amritsar, who could stop you?’

The reply came, “No I will not go, Those people do not want me there.”

Perhaps there is someone who can unravel this secret for me, because after this he never did set foot on that patch of earth again. Doctor sahab had himself resolved to forget his past, to the extent that even mere mention of it was not to be tolerated. Perhaps the wound was too deep. It’s mouth would not close, but it was his own tongue that was stopped forever.

The children moved towards communism, Apa’s religiosity rose to the surface, and Doctor sahab sank deeper underground, in a strange kind of captivity. The craft of life was moving, passing from oar to oar, but Doctor sahab just lay there peacefully reading. This was the end that most nationalist Muslims came to. Some were driven mad by grief and anger, some were struck dumb caught between hope and despair, some trained their sights on the seat of government, and some were left forever exhibiting the woeful memories in their hearts/their wounded breasts. Only a few could ever steer an even course.

These were a defeated people after all, who had lost as much to their own as to those were strangers to them.