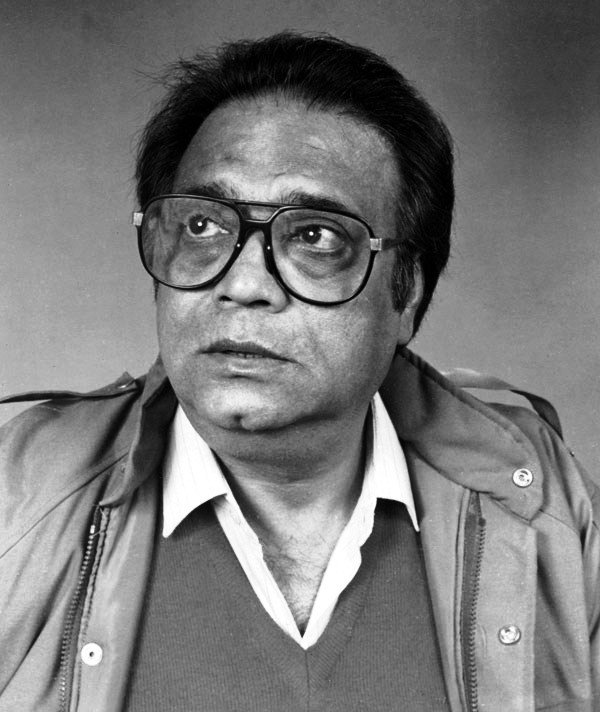

Few beyond West Bengal may have heard the name of Nemai Ghosh. Though he is extremely low-profile; his name is synonymous with Satyajit Ray and with his still camera. He was Satyajit Ray’s official photographer beginning in 1969 when actor Robi Ghosh introduced him to Ray on the sets of Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne. He did not bother to get his collection recorded with the Guinness Book of Records but perhaps across the world, he is the only photographer who has in his collection more than one lakh photograph negatives of Satyajit Ray clicked between 1969 and the time Ray passed away.

Originally from group theatre, Ghosh chanced upon photography through a strange twist of fate. “One evening, as I was waiting to get to the rehearsals for a play, munching peanuts, a friend of mine told me that someone had forgotten his camera in a cab. My friend had picked it up and was already offered Rs.600.00 for it by another friend. I don’t know what prompted me to buy the camera off him. “You already owe me Rs.240.00. If you give the camera to me, I shall write off the loan.” He left the camera with me. I turned it around and looked into it, examining it closely. But I could hardly understand how it worked. At the time, a friend of mine who worked as an assistant cameraman in films offered to teach me the ropes. One day, theatre actor Robi Ghosh took me to see the shooting of a Ray film. The rest, as the saying goes, is history, he reminisces.

Delhi Art Gallery has digitized Ghosh’s work of more than one lac negatives, and present around one hundred and seventy archival prints at the Harrington Street Art Centre in Kolkata. Delhi Art Gallery brought out a superbly printed coffee table book of Ghosh’s photographs of Ray caught candidly in a myriad of moods – reading, writing, concentrating, pensive, working, looking through the lens on location, pointing a finger to direct action and so on. Pramod Kumar KG curator of the exhibition said, “Ghosh’s photographs of Ray at home and on the sets suggest a rare intimacy; with the poignancy of these images of the master at work, during and in many cases, enacting roles.”

His photographs on Ray are exhibited at the permanent gallery of St Xavier’s College, Kolkata, and at Nord Pas-de-Calais, France. He has documented the making of films such as Jukti Takko Gappo by Ritwik Ghatak, Interview, Calcutta 71 and Ek Adhuri Kahani by Mrinal Sen, Paar by Gautam Ghosh and Ijjodu by M S Sathyu. Ghosh photographed great masters Jamini Roy, Ramkinker Baij and Benodebehari Mukherjee over the years 1969 and 1970. He went back to his interest in documenting master artists from 2002, photographing more than 30 major Indian painters and sculptors at work, resulting in a massive suite of photographs of the best minds in contemporary Indian art at work.

Ghosh has occasionally worked with other directors in film assignments. He was the still photographer for several films including Utpalendu Chakravarty’s Chokh (Eyes) (1982), Mrinal Sen’s Interview (1970), Calcutta ’71(1972) and Ek Adhuri Kahani (1972) and M.S. Sathyu’s Kahan Kahan Se Guzar Gaya (1981). “I am choosy about film assignments because I insist on reading the entire script of a film before accepting the work. This seems to puncture the egos of many filmmakers because after all, I am only a still photographer. But I do this because I work hard to sustain the high standards Ray helped me establish. For magazine work too, I look at the magazine myself to examine the processing and printing so that the quality of my original work does not fall because of bad printing” says Ghosh.

Moving beyond Ray, he has photographed the land and the people of Kutch in Gujarat (1995–97), Bastar in Chattisgarh (1998–99), Bonda Hills in Orissa (2007), the Apatani tribals in Ziro in Arunachal Pradesh (2010). “You cannot even begin to imagine what a long struggle it was to capture the lives and habitats of the adivasis of India living in remote places, inaccessible by any form of public and private transport, involving miles and hours of trekking on foot in terrible climatic conditions and all this when I was not exactly young,” reminisces Ghosh who celebrates his 85th birthday on May 8 this year. “The three things that have seen me through my struggles to establish myself are – the tenacity of purpose, discipline and hard work. I learnt discipline from Utpal Dutt when I trained under him as part of his Little Theatre Group. The same applied to Ray.” One of his sons, Satyaki Ghosh, is currently one of the best-known names as a brilliant photographer in B & W of performing artists, cinema, and fashion.

Following Ray’s demise, Ghosh’s creative energies sought other directions, other subjects, other worlds. One is Kolkata, the city he was born in, grew up and still lives in. Nemai Ghosh’s Kolkata is a brilliant aesthetic and creative tribute to the spirit of this city. The images reproduced in Black-and-White, are complemented with text and captions by Shankarlal Bhattacharya and Ghosh’s own quotes. Published in 2014, the coffee table book is a collector’s item. About this book, he says “I hear a lot about this city. Some call it a city of poverty and despair. Some find it to be one of politics and rallies. And there are many who believe in its deep root in art and culture. Whatever be the case, I find life here and love. What draws me to Kolkata is the human element and its spontaneous expression. Every moment of the city distils a narrative of epic possibilities and I, as a flaneur, have framed all of that. From the alleys to the highways, my lens has been doing its job. It is not a comprehensive, definitive compendium of Kolkata. Neither is it meant to be one. It is my Kolkata, the way I have seen it evolve through time.”

Every page, every photograph and every paragraph explaining each picture throws up the true spirit of the city of Kolkata such as roadside performers and vendors, the city seen from the rooftops, a historical shot of Jyoti Basu addressing the first United Front Rally at the Maidan, instant portrait painters who have disappeared into anonymity with the advent of globalization and shopping malls, fortune tellers, the person playing monkey tricks to the gathering crowds, huge crowds moving towards Strand Road to begin their pilgrimage to the Ganga Sangar Mela, the then then-debutant actor Ranjit Mullick crossing the street, cabaret dancer Shefali captured in action that can never fade away if the history of the city was to be written in pictures.

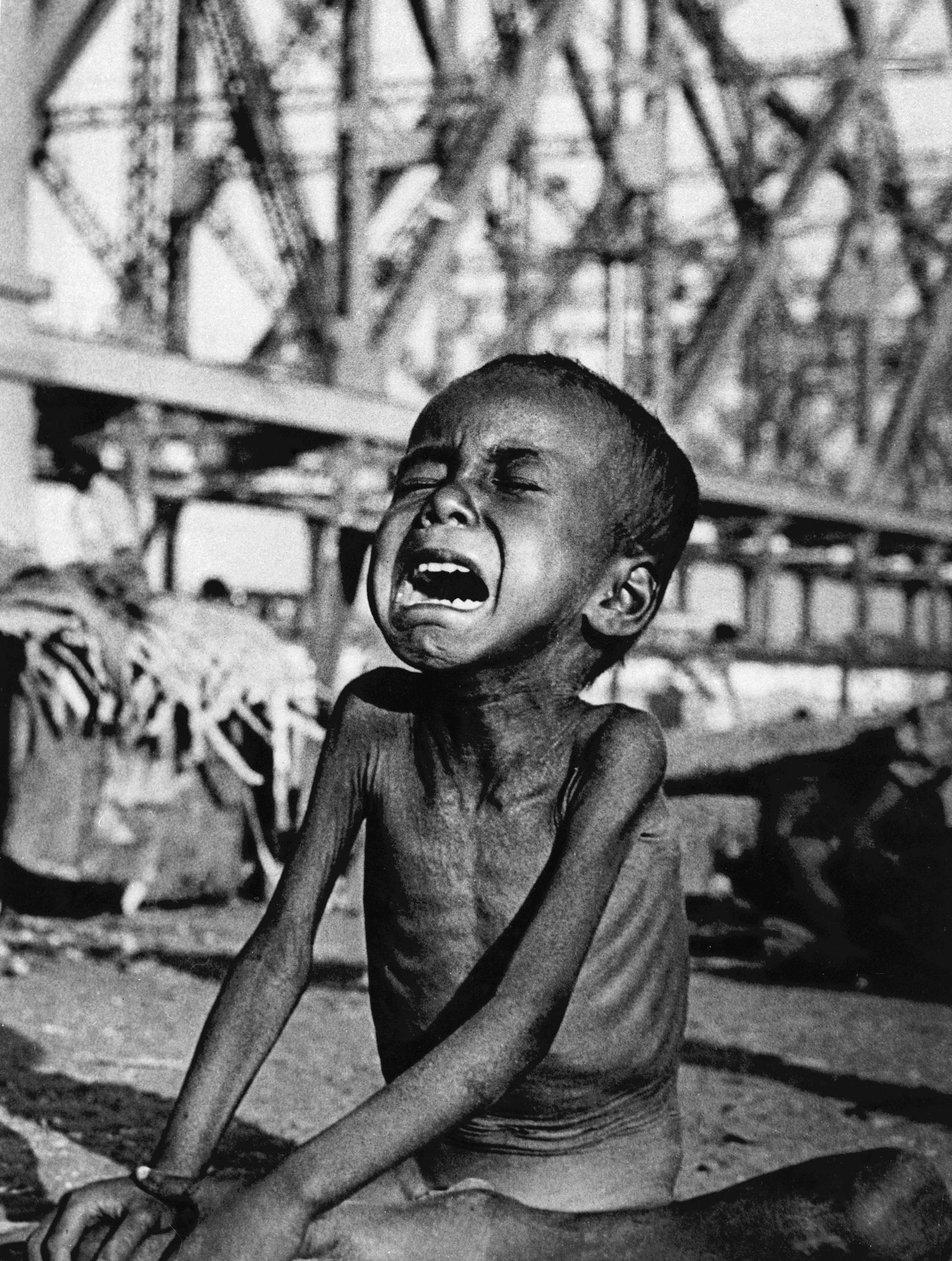

This includes a brilliant series on street performers such as fortune tellers and the monkey trick man plying their trade under the Sahid Minar, a moving series on the hand-pulled rickshaws of the city, a historic shot of Jyoti Basu addressing the First United Front rally at the Maidan, instant portrait painters who have since disappeared from Gariahat, massive crowds heading for the Gangasagar Mela from Strand Road and even Irrfan Khan and Tabu walking along the gardens between shots for Mira Nair’s film The Namesake, the weeping figure of a skeletal child sitting under the huge Howrah Bridge, a shot of a very young Ranjit Mullick crossing a street during the shooting of Mrinal Sen’s Interview and a shot of the maidan in the afternoon clicked from the top of the Shahid Minar. One can get a glimpse of Shefali, the cabaret dancer of yesteryear caught in a pose during a performance. There are rare photographs of historical value. One shows Ray and Ghatak sitting together. Another catches Ray unawares in silhouette. A third is a priceless image of Ajoy Mukherjee, his deputy Jyoti Basu and Minister Jatin Chakraborty in a single frame. There is an architectural statement that places the Thacker Spink Mansion, the RBI Building and the UBI Building together. Painter Paresh Maity in second preference is seen looking at a forgotten idol of Kartik, the Warrior God.

“Today, the word “camera” is an integral part of my name. Wherever a group of people discusses me, the word “‘photograph” comes up almost naturally. The most interesting part of my story is that to be a photographer was never a part of my life-plan.” These are the opening lines of the book Manik-da published in 2000 in Bengali. Written plainly, the author-photographer traces how his passion for the theatre, developed since boyhood, and his interest in lighting, which is an integral part of the theatre, slowly but surely took him on a long and exciting journey with one of the greatest filmmakers the world has ever produced. The book is a slim volume of 96 pages, bound in paperback, and is equal parts text and image (prints of B & W photographs of Ray taken by Ghosh himself). The book is a collector’s item for cinephiles and fans of Ray.

Way back in 1991, a photo biography on Satyajit Ray was published under the title – Satyajit Ray at 70. It documented a collection of B & W photographs of the great master of celluloid taken by his photographer, Nemai Ghosh who, by then, had been Ray’s photographer for 25 years. It was published by the Eiffel Editions of Belgium that went on to institute a travelling exhibition of these photographs with a world premiere on June 20, 1991.

His motivation for photography is the thought – what is viewed by the natural eye should also be capable of being grasped through the lens of the camera. His ultimate aspiration is to be able to photograph completely in the dark, totally without light.”I am positively allergic to the flash in photography. The flash, in my opinion, cannot capture the drama of life. Only natural light can achieve this perfection. This is why I try to shoot as much as I possibly can, in natural light.”

Photographs are no longer purely a recording instrument documenting faces and events. Photography has journeyed a long way since the invention of the first plate camera in 1851. Ghosh for more than five decades has been documenting history, recording not only Ray but artists, painters and musicians, ordinary people, using his camera and his ingenuity to make strong political statements or satiric comments on the state of things. The word “photogenic” does not exist in his dictionary because he believes that this is totally in the hands of the photographer. Ghosh’s photographs have greater significance than the written word because of their visual authenticity and archival value.

“The three things that have seen me through my struggles to establish myself are –the tenacity of purpose, discipline and hard work. I learnt discipline from Utpal Dutt when I trained under him as part of his Little Theatre Group. The same applied to Ray and I re-learnt them from him again,” he says, adding, “But my ability to catch the exact mood, the precise moment, the particular posture, the body-movement, the facial expression are all rooted back to my theatre training” he sums up.

Read More:

On Satyajit Ray’s birthday, remembering dignified criticism of historical films

Mrinal Sen: “A perfect combination of a wise-old-man and completely young at heart”