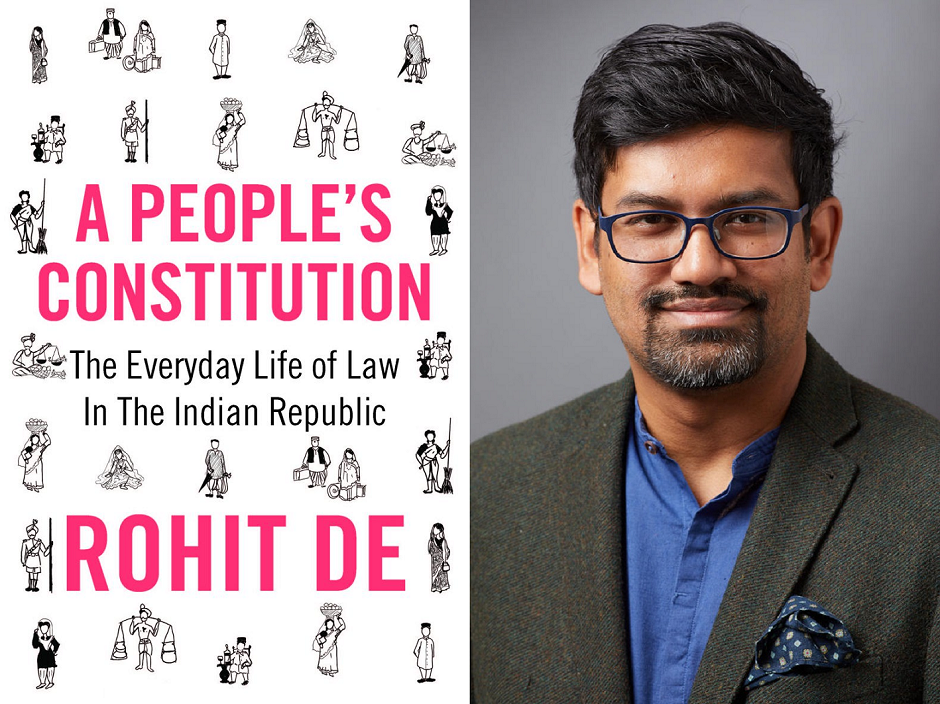

Rohit De’s recent book, A People’s Constitution, has received wide acclaim. The book tells the story of how India’s constitutional culture was built. As against conventional views of India’s constitutional history, De points out that it was the travails and struggles of ordinary citizens that shaped our understanding of rights and liberties. The Indian Cultural Forum speaks to Rohit De about his book and the current challenges of constitutional practice in India.

ICF Team: As a book on the Indian constitution, A People’s Constitution has unlikely protagonists – from butchers to small traders to sex workers. Could you talk to us about the basic perspective animating your book?

Rohit De: The question I really began with was – “Does the Indian constitution matter?” Outside the self -invested legal academy, I saw deep skepticism about its impact. The first and most obvious reason was that the promise of “justice, economic, social and political” was far from being achieved and the small victories were driven by electoral mobilisation. Secondly, the constitution itself had strong structural continuities with the colonial Government of India Acts which expanded and centralised state power. Finally, there was a shared skepticism from both the right and the left that the constitution was not organic to India. As K. Hanumanthaiah had lamented in the constituent assembly, instead of the “music of the veena and the sitar.. what we got was the discordant notes of an English military band”. Or in Dr Ambedkar’s words, the constitution presented a democratic top dressing on a deeply undemocratic soil. Even those who found much to admire in the political vision of the constitution seemed to concede that it did little for the lives of ordinary people.

While agreeing with much of this criticism, I was struck by the fact that despite these constraints, ordinary Indians turned to the constitution from its earliest days to stake claims both in the courts and in the streets. This was a far cry from the popular belief that poor and marginal citizens repose little faith in the law. Indeed, after independence rates of civil litigation, i.e. Indians taking other Indians to court, actually declined. However, what steadily increased was litigation and claims against the state.

The book turns to the relatively understudied provisions of constitutional remedies to argue that the constitution came to matter in everyday life, and did so often because of repeated usage by some of the poorest and most marginal citizens. My argument does not rest on the claim that the constitution is emancipatory or repressive (both cases can be made), but that it has clearly been useful to large numbers of people. This is very much a work of history, focusing on a period where the rules were being worked out, and where the courtroom was often the space of the unexpected for both citizens and the state. My research began with looking at “constitutional resistance” to attempts by the postcolonial state to transform everyday life, through policies like prohibition, license-permit Raj, ban on beef, municipal licensing and regulation of sex work. This led to the emergence of a certain kind of citizen-litigant, who would use the “state’s language to resist the state”. Not all marginal groups were well represented in the period; peasants and landless labourers, for instance, enter the constitutional field quite late. But marginal figures on the edges of the urban economy, be it big cities or small Kasbah towns, faced the first push of regulations and found themselves turning to the constitution to make their claims.

It is also becoming increasingly clear that despite being framed by political elites, large swathes of Indians were interested and engaged in the process of drafting the constitution, flooding the Constituent Assembly with letters and petitions and debating the constitution in a variety of forums.

ICF Team: Given the centrality of the constitution to Indian social and political life, what do you think explains the doctrinal focus of scholarship on the constitution till now?

RD: There are a number of reasons for this. The audience for constitutional law, until recently, was imagined to comprise largely of legal practitioners, be they lawyers, law students or judges. The emphasis, as a result, was on producing scholarship that was useful to practice and, therefore, centered on doctrine. The key questions were framed around the holding of a case, its value as a precedent, how it could be distinguished from other cases etc. There, of course, remained important exceptions to this – for instance, the work of Marc Galanter and Upendra Baxi or the early scholarship of Rajeev Dhawan, which attempted to understand the constitution and the court system structurally i.e. from the point of view of political economy or class composition. Apart from a few such exceptions, the favored form of writing about the constitution was that of a treatise, a how-to-book for practitioners.

There was also work done by an older generation of political scientists – Susan Rudolph, Lloyd Rudolph, Francine Frankel and George Gadbois – which focused on courts and judges as a way of understanding the larger scale politics of the state. I would also include Granville Austin’s magisterial volume on the Supreme Court in this category. However, since this work was institution-centered, it focused on the “big narratives” and tended to treat doctrine as a variable. Feminist public law scholars like Lotika Sarkar, Brenda Crossman, Ratna Kapur, Kalpana Kannabiran and others were perhaps the most effective in bridging the gap between doctrinal study and lived experiences of individuals.

Historians were for a long time suspicious of both the constitution and the appellate courts. There had been an imperial tradition of “constitutional and administrative history” which was largely aimed at those preparing for civil service examinations. In this narrative, constitutional law was clearly about understanding a roadmap of power, and its actors were seen as elite figures. As historians grew more interested in looking at the lives of understudied ordinary people, they turned away to other forms of history.

What I attempt to do is to recognize that the constitution shaped the everyday lives and imaginations of Indians in significant ways. Perhaps a way to describe it would be a social history of doctrine. As I argue in the book, when we ask “what did the court do?” in a certain case, we fail to consider the real contestations among judges, litigants, lawyers, and other actors in the presentation of legal claims. To understand how constitutional law works in India, then, it is necessary to understand what people (whether legal officials or ordinary citizens) believe law is and what they do with this knowledge as they make decisions in their daily lives. We have to move beyond asking “who won?” or “what was the holding?” to trying to understand why people make repeated engagements with the law (or also why in some situations they do not).

I am glad to note that I am joined by several scholars in this endeavor. The work done by Nandini Sundar and Anand Vaidya on tribal engagements with the law is extremely exciting and based on rich enthnographies, as is the emerging scholarship on dalit constitutionalism.

ICF Team: There is a widely accepted narrative of ever-expanding writ jurisdiction in post-emergency India. Certain individual judges like PN Bhagwati and VR Krishna Iyer are often seen as heroes of this story. In what ways does your book complicate this picture?

RD: There has long been a conventional narrative about the Indian Supreme Court. That the court was conservative in its early years, and largely came into conflict with the government over the rights of the elite and the propertied. The court was also unable to stand up for civil liberties and the rule of law during the Emergencies. In order to rebuild the court’s legitimacy, in the 1980s the Supreme Court, led by Justices Bhagwati and Krishna Iyer, actively encouraged Public Interest Litigation and sought to reduce procedural hurdles to justice. In the words of Upendra Baxi, this marks a moment when the “Supreme Court of India became the Supreme Court for Indians”. This is a narrative that we are taught in law schools, and has been reiterated by the court itself on repeated occasions.

However, over the last decade scholars including Usha Ramanathan , Kaveri Gill, Gautam Bhan, Nivedita Menon and Aditya Nigam have been increasingly critical of this narrative, drawing attention to the fact that since the late 80’s, PIL’s have increasingly been an instrument used by judges to take control over questions of administration and governance, and define “public interest” to force an undemocratic, technocratic and neoliberal vision of governance, overriding efforts by the poor and marginal groups to mobilise politically. So the “right to a clean environment” was often mobilised to upset decades of negotiations worked out by the urban poor who were squatting in slums, or small traders who legitimised their workshops and factories.

While others have explained this shift through class interest, the rise of conservative judges and a dominant neo-liberal discourse, Anuj Bhuwania goes a step further arguing that the PIL was a continuation of the Emergency through the judiciary, instead of being an act of judicial redemption. The Emergency, at its core, allowed the abandonment of procedural safeguards in the name of “the people”. It is therefore unsurprising that judges like P.N Bhagwati, who ruled in favour of the executive during the Emergency, helmed the PIL revolution, and that stated goals like slum clearance, urban beautification and abolition of bonded labour echo the 20 point program of the Emergency

This body of work challenges the second part of the PIL narrative – the idea that the PIL was a moment of redemption and reorientation of the Supreme Court for the poor. My work challenges the first assumption, that prior to the Emergency the courts were largely conservative and a refuge of the elite. I show through archival evidence that certain marginal citizens were successful in using the constitution and the courts to mobilise and secure their aims. The courts, despite the overall commitment to conservative procedure, did make some space for questions of public interest, most notably in the case of prohibition.

More significantly, I argue that for some groups, the procedural gambit worked better than a substantive claim. If I may quote from the book: “ The four sets of litigants in this book represent groups that are marginal and have limited social capital amid a wider public… and had few allies outside their own groups. They stood outside the consensus of what a good Indian citizen should be. Therefore, an argument rooted in their rights as prostitutes, traders, or butchers would not find popular resonance outside their groups. However, by framing their problem as one of procedure, these litigants were able to deflect attention from themselves and generalize the problem to the broader public. This was an interesting contrast to colonial India, where emphasizing particular rights was more profitable, but all of them were rooted in custom and religion.”

Who does informality and reducing procedure benefit? Conventionally, the answer is that procedure is a form of systemic violence and greatly disadvantages the poor. This clearly comes through in Justice Krishna Iyer’s dismissal arguing that “procedure is but a handmaiden for justice”. However, the real story is a lot more complicated. Patricia Williams, in her Alchemy of Race and Rights, argues that informality works better in situations where all parties share some degree of trust, and advantages those who are better networked. I hope my book, along with the recent scholarship, will lead to a more sophisticated understanding of procedural reforms.

ICF Team: You make the point in your book that electoral minorities have been overrepresented in constitutional cases before the courts. What do you think explains this?

RD: This was in some ways a surprise. As I started researching on the book, I was interesting in looking at how ordinary citizens challenged new regulations after independence. While creating the first data set, I began to notice a certain similarity in the kinds of petitioners challenging particular kinds of legislation. It helped that in the early writs, petitioners also identified themselves by their community – “A Parsee resident of Colaba” etc. While more quantitative research needs to be done, within my data certain distinct communities seemed overrepresented.

Why was this the case? Something profoundly changed in both the character and rhetoric of the state with the coming into place of the constitution. Under colonial rule, Indians were subjects and were often administered through their community identities. Rights claimed were often framed on the basis of preserving “ancient customary liberties” or using Queen Victoria’s Proclamation of 1858 to assert a right to religious practice. Thus, Parsis in the 1930s challenged prohibition as a breach of both customary rights and ritual practice. Secondly, colonial representation was based not on universal franchise but the representation of interests; there were special seats in the legislature for “Indian Commerce”, “Women” etc. The constitution transformed this and created an equal relationship between the individual and state; it also subordinated the claim for particular rights to that of general interest (for example, the restrictions in Article 19). For Nehru’s government, the basis of governmental legitimacy lay in the fact that it had won a popular election.

However, what about interests that could not be represented through the institutions of electoral democracy? These included both religious and cultural minorities, but also groups that carried a pejorative public image. For them, the courts remained the only resort.

The idea of an electoral minority challenges conventional understandings of marginality, for instance social and economic deprivation. As Namita Wahi points out, at least two of the major groups, Parsis and Marwaris, occupy economic privilege, and the others – street vendors, prostitutes and butchers – have control over some capital. This is why turning to cultural sources from the 1950s was critical. I was able to show that these groups enjoyed little public legitimacy and support. The Marwari shopkeeper was a figure that was villainised in both government propaganda and popular culture, the prostitute seen as a figure of decadence and contagion, the Parsis portrayed as effete and anglicised, and the Muslim butcher demonised by an assertive Hindu public.

Group rights, particularly minority rights in India, have largely centered on questions of culture (language, religion, and status). This is despite Ambedkar’s memorandum on minority rights, which noted that the “connection between individual liberty and the shape and form of the economic structure of the society may not be apparent to everyone . . . nonetheless the connection is real”. It is also important to remember that community identity was not just a mark of culture, but was closely tied to the market. In a caste-based society, electoral minorities are not just members of a socioeconomic class or followers of a certain ideology but are inextricably linked to ascriptive identities.

ICF Team: In your book you describe the aura of secrecy that surrounds the Supreme Court Record Room, an archive you have drawn heavily from. Do you think there needs to be a concerted effort to make such legal archives more accessible?

RD: Most courts in India are designated courts of permanent record. This means that they have to maintain their records for all time. However, these records (with a few exceptions like the Calcutta High Court, or the papers relating to the Lahore Conspiracy Case) have remained on court premises, largely moldering away in basements. This is partly because legal imaginations do not see the court record as useful, except to the parties in the case. The published judgment is the final word on the case, framed by the judge’s authorial voice. Its chief value outside of the parties concerned is in its role as legal precedent. When I was trying to get access to the Supreme Court records, I did not meet with opposition but mostly bemusement and curiosity as to why these would be useful.

What these records are able to show are the contestations that go into a legal dispute, and often reveal the silences that remain in the judgment. For instance, one of my chapters is centered around the Mohd Hanif Qureshi case, often reproduced in reports and textbooks as Mohd Hanif Qureshi and Others. It was only on examining the case file that I discovered that “the others” included close to 3000 individually named petitioners from hundreds of villages across North India. This changed both the scale and nature of the intervention. Similarly, the judgment itself is framed as a question of religious freedom, and becomes a precedent for it. However, examining the petition one sees that this was almost an afterthought by the petitioners, who advanced very limited material to support it, and largely saw the cow slaughter ban as an economic impediment to their trade and profession. There has been exciting work coming out from High Court archives by scholars like Mitra Sharafi, Durba Ghosh, Julia Stephens, Kalyani Ramnath and others, that offer new ways of understanding both Indian history and the legal system[i]. Sharafi, for instance, works with the Parsi Matrimonial Court records and is able to show how Parsis, particularly Parsi women, were able to use and transform community norms through engaging with the colonial legal system. Kalyani Ramnath’s use of the Madras High Court records shows a world of legal transactions that tied Madras to Burma, Singapore and Malaya, and tracks what happened after independence when state borders came up.

There is also a pressing need for quantitative research on the courts using these records. Apart from Nicholas Robinson and Abhinav Chandrachud’s work on the Supreme Court and the Bombay High Court recently, the last major piece of research was by Rajeev Dhawan on the Allahabad High Court.

All of this is to say that there is much to be done in preserving these records and making them accessible. An easy way would be to move many of the older records to the state archives, as is the practice in the UK , Sri Lanka and Kenya. These are designed to preserve and make available records for academics. Currently, the records are largely stored in cloth bundles and dumped in basements. This makes retrieval almost impossible and puts the documents in danger of being damaged. There is a concerted effort to digitise these records, but the terms of the digitisation remain unclear. I have also heard the rather worrying rumor that the physical records are being destroyed after digitisation. While digitisation can be a good way of preserving and making records accessible, these need to be done with care and under supervision of trained archivists and historians, particularly when the digitisation is only partial.

The Supreme Court Museum is an under-utilised resource and could play a larger role in preservation. Other initiatives could include preserving the private papers and correspondence of key legal actors including lawyers, judges and non-governmental organisations. The PUDR papers in the Nehru Memorial Library, for instance, or the papers of Justices Gajendragadkar and Chagla, have been invaluable resources.

ICF Team: Do you think that despite the remarkable progress the Indian judicial system has registered in terms of constitutional practice, equitable access to the law remains a problem even today?

RD: Absolutely. How does one explain the persistence of Indian constitutionalism despite the malaise of the legal system? One of the arguments I make in the book is to separate constitutional litigation from the rest of the legal system. As a recent study shows, levels of civil litigiousness in India, i.e. the number of Indians who turn to the law to solve problems with their fellow citizens, has actually dropped sharply since independence. Most Indians, of all social classes and backgrounds, are reluctant to engage with courts in ordinary matters. In contrast, rates of litigation against the state have steadily increased after independence, both due to availability of constitutional remedies and the greater intervention of the postcolonial government in everyday life. This is also a product of judicial architecture; the High Courts and the Supreme Court are staffed by better judges and advocates, and face a greater degree of media scrutiny, than district courts. While delays are also endemic, they are less so than in the district courts.

In some ways, this mirrors the Indian state, which often invested in creating a few institutions of international repute and excellence rather than improving standards of ordinary institutions. This is perhaps clearest in the field of education when we compare ourselves to other postcolonial countries. For instance, the state subsided and promoted universities that produced world class scholarship and a technically trained manpower, but spent a marginal portion of the GDP on primary education. One could argue that this is a result of state capture by a certain group of elites, who transferred resources to build institutions that they could access without improving the access of the masses.

The trend changes over time, however, with greater democratisation of these spaces and increased access. It is worth asking in what ways access to justice can be made equitable. Why, for instance, are constitutional remedies only limited to the High Courts and the Supreme Court? Why cannot district courts exercise writ jurisdiction and hear certain kinds of administrative cases? If more was at stake in the lower judiciary, there would also be a greater urge to improve infrastructure and reform processes. Similarly, as Nicholas Robinson’s research shows, the Supreme Court disproportionately hears cases from Delhi and the surrounding regions[ii]. Would it make sense to create benches elsewhere in the country, have a travelling court, or create an intermediate court of appeals for different regions? Lastly, and most urgently, there is a need to rethink and reimagine legal aid and legal awareness. I am encouraged to see that some parties have made access to justice a political issue in their manifestos, and hope they will be seriously funded and implemented in the future.

[i] Sharafi, Mitra. Law and identity in colonial South Asia: Parsi legal culture, 1772–1947. Cambridge University Press, 2014; Kalyani Ramnath, Boats in a Storm: Law, Politics, and Jurisdiction in Postwar South Asia, PhD Dissertation, Princeton University, 2018; Julia Stephens, Governing Islam: Law and Secularism in Modern South Asia, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

[ii] Robinson, Nick. “A Quantitative Analysis of the Indian Supreme Court’s Workload.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 10, no. 3 (2013): 570-601.