Image Courtesy: Scroll

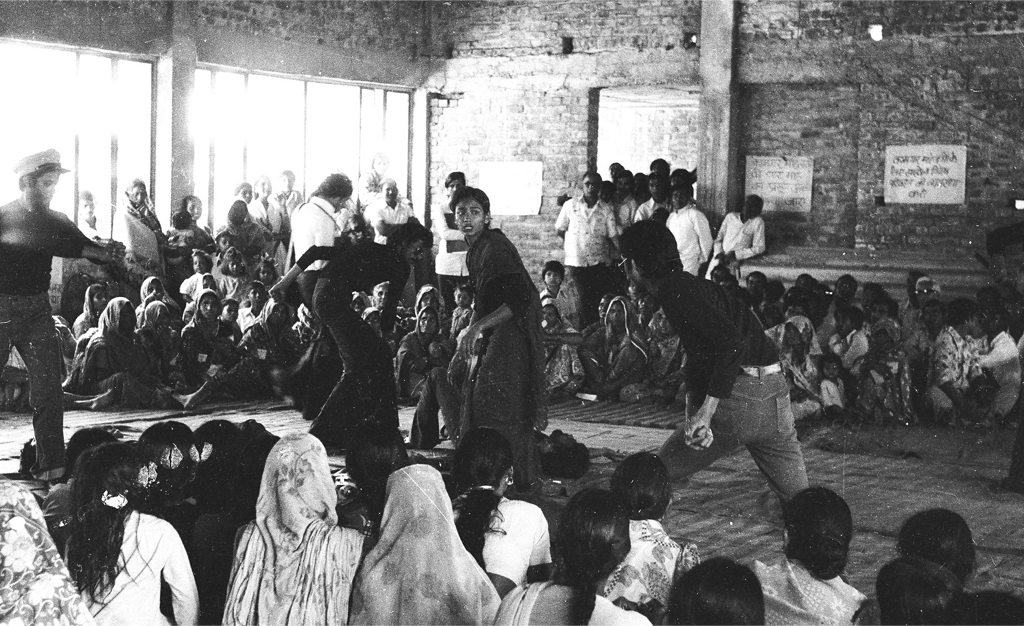

Written overnight by Safdar Hashmi and Rakesh Saxena, Aurat, a landmark play by the Jana Natya Manch (Janam) portrays what it means to be a working-class woman in India and foregrounds the co-dependent nature of women’s struggles and working-class struggles. Created for the first North Indian Working Women’s Conference in 1979, the play connected with the emerging women’s movement in the late 1970s and early 1980s. With over 2500 shows and translations in multiple languages, Aurat remains Janam’s most successful play till date.

The main character of the play was Aurat, who had no particular name, nor religion, nor caste, nor regional identity. Moloyshree Hashmi, who was 25 at the time, enacted the many phases of a working-class woman : a student who asks if a girl from a working-class family has the right to education; a married woman who is oppressed at the hands of her husband who is also a worker; a woman who faces sexual harassment at a job interview; a woman who is arrested for joining a demonstration against unemployment; a working-class woman who is retrenched but finds solidarity and strength in struggle.

The intersectional nature of the play is emphasised through the play’s form itself. The play opens with a rendition of the poem “I’m a Woman” by Marzieh Ahmadi Oskooii, an Iranian teacher and revolutionary who was executed by the Shah of Iran in May 1973. In Aurat, the poem is adapted and spoken by all members of the cast, who introduce the Woman in a gripping way. Five to six men move in circles around a woman who is not seen by the audience until they reach the centre of the street-stage where the flower shaped formation suddenly bursts open and the woman comes out. Throughout the thirty-minute long play, this formation is maintained, such that, at any point, no matter where one watches from, the Woman is always at the centre. This was meant to symbolise the precarious existence of a working-class woman in India.

On February 21, 2019, at a seminar commemorating 40 years of Janam, both old and new members of the theatre group, shared their memories of the plays, the rehearsals and the times. One of the plays discussed at the seminar was Aurat.

Brinda Karat, who was the General Secretary of the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA) from 1993 to 2004, was one of the speakers at the event. Emphasising on the importance of a play like Aurat in a pre-AIDWA time, Karat recounted how Janam served as a bridge between intellectuals and workers.

In the mid-1970s, she worked closely with the textile workers union in North Delhi. Textile was one of the biggest industries in the region, employing nearly two thousand workers, who were mostly men. Women, on the other hand, were recruited in the handloom sector which involved spinning the loom. It was home-based work outsourced by mill workers, based in regions like Wazirpur, Azadpur, and Pratapbagh. Activists like Brinda Karat were working towards organising a coalition between the textile workers and handloom workers. They conducted a survey around different parts of Delhi to inquire into the working conditions of women—their problems, circumstances, and experiences— the results of which were going to be shared at the first North Indian Working Women’s’ Conference on 25 March 1979.

Moloyashree Hashmi and Safdar Hashmi were in talks with Karat about the state of women workers and it was decided that a play would be made on the issue to be staged at the conference. Aurat was born out of these discussions and readied in ten days.

KM Tiwari, one of the speakers at the seminar who had worked with unions in the Ghaziabad and Sahibabad industrial area that time said, “Nobody tells you about the lives of working women. If a woman and a man are working for the same amount of time on the same machine, why should they not be paid the same thing? This is where the “equal wages for equal work, for both men and women”, concept begins and extends to questions regarding rights in the household too”.

For a play that was challenging the gendered nature of the trade unions and pushing for reform from within, it was inevitable that acknowledgement and resolution of women’s rights would cause some tension. “If you look at the play, the woman is oppressed at the hands of her husband, who is also a worker. So, there was apprehension, that if we spoke about women harassment within the workers union, it could create a chasm within the movement. People were afraid that it will make enemies of workers and weaken the movement which was still in its early stages,” Karat recalled.

While the working women’s campaign was challenging the existing patriarchal trade union structures, through its mobilisation of women workers from informal sectors, the campaign was also offering a radically different approach to self-organisation from “below” rather than through rich, upper caste patronage from “above”. This was a break from the mainstream women’s movements.

“We had two issues. One was to take the working women’s concerns forward with the trade unions and march ahead with them. The other was the struggle with the dominant women’s movement at the time. We were clear that if we did not bring the voice of the working-class women into the bigger feminist movements, if we remained limited to the ideology of the urban women resistance groups, then the naari-mukti andolan would always remain incomplete,” Karat said.

“This is something we speak about now – women having equal rights in every space – but that conversation had not fully matured then,” she added.

When the play was finally staged on the day, it moved Karat to tears. “Aurat spoke in a multidimensional voice that not only inspired women from the working classes but had a lasting relevance for women’s movements in India and across the world”, she said.

Through a series of episodes which enact scenes within a home, at the marketplace, in a marriage, at a college, on the roads, at a job interview, and finally in a factory, the play moves from the domestic sphere to the public to show the links between patriarchy and capitalism, and how the only real challenge to patriarchy comes from proletarian values1.

This is a part of a series of posts, leading up to the International Women’s Day, that the Indian Cultural Forum is dedicating to women asserting change in cultural, economic, and socio-political spaces.

1. A Critical History of the Jana Natya Manch of ‘international fame’.

Read More:

40 Years of Jana Natya Manch – A Journey of Struggle and Hope

“Writing has become a response to the political horrors of the present”

The Past Still Infects the Present