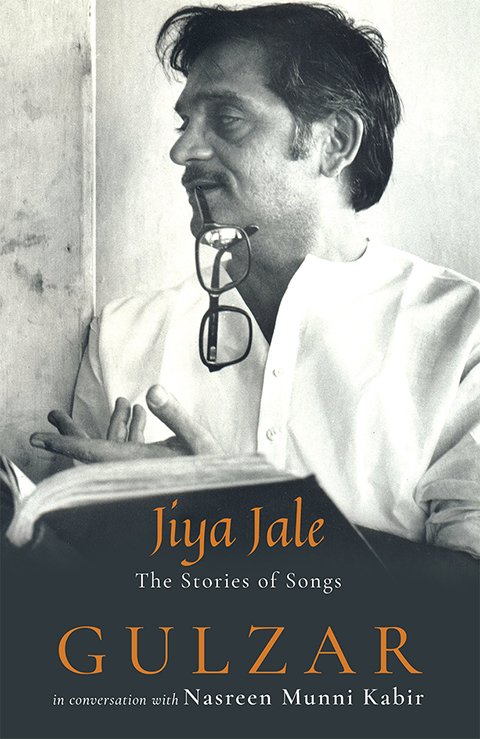

After In the Company of a Poet (Rupa Publications, 2012), writer, filmmaker, subtitler and translator Nasreen Munni Kabir’s second book with poet and lyricist Gulzar takes the reader through some of Gulzar’s best-known Hindi film songs and narrates the stories behind them. Jiya Jale: The Stories of Songs emerged out of conversations about the art and craft of subtitling conducted between early 2017 and April 2018. In these excerpts, Gulzar reveals if visuals inform his writing, the gender-informed system of linguistics in Hindu-Urdu girl-boy romances, on lyricists today and much more.

Image Courtesy: Speaking Tiger

Image Courtesy: Speaking Tiger

Nasreen Munni Kabir: When you write a song, do you ever think a particular line would work well in mid-shot or long shot?

Gulzar: That is not the role of a lyricist. The picturization is entirely the director’s job or the choreographer’s. But yes, images and visuals do come when we’re writing and composing songs.

I wrote the dialogue and songs for Jabbar Patel’s 1986 film “Musafir” and while Pancham, Jabbar Patel and I were working on “Bahut raat hui, thak gaya hoon mujhe sone do” [It is late, let me sleep], Pancham asked if there was a river in the scene. I asked him to explain why and he said he wanted to add the call of a boatman between the verses.

This would look silly if the song was going to be picturized on a mountaintop—the visuals have to match the words.

If certain images come to you while working on a song, you tell the composer. So he can use an appropriate instrument. Creating songs is teamwork. It is not the result of one man’s input. That is the beauty of cinema—working the scenes out together.

Don’t forget the film song has to also make some impact outside the film itself. This makes the song popular. It has to be specific to the character yet universal, so it can stir the emotions of many.

NMK: Today’s technology and methods of communication have helped connect music and musicians all around the world. And perhaps widened the choice of musical instruments?

G: The horizons have expanded. Indian composers are on par with world musicians and they do use all kinds of instruments today. These choices were not available to earlier masters.

Everything has changed. Today when our heroines appear in a film, they say ‘Hi!’ There’s no more of that coy, eyes-lowered ‘Namaste-ji’ [both laugh]. That time has long gone!

[…]

NMK: What must you bear in mind when writing a song that works as a conversation between a boy and girl? Bearing in mind that unlike English, Hindi and Urdu have a gender system.

G: You give the director a song knowing that this line is for the girl and that line is for the boy. Suddenly the director tells you, supposing the girl sings this line instead? How will the boy reply? So the gender of the words has to change—the thought may remain the same. “Main kehta hoon” instead of “Main kehti hoon.”

The little cleverness we lyricists do is worth noting. We say “Hum kehte hain…” This way you don’t commit because you can use “hum” for boy or girl. So we avoid being specific, in case the directors change the point of view of a verse when they film the song. Hindi provides you with this option.

NMK: I think lyricists today have a big disadvantage because many film characters do not look right when expressing themselves in song. And lip-sync songs look out of place in the more realist stories of current Hindi films. Lyrics aren’t as close to the narrative as they once were.

G: That is why most songs play in the background and the hero and heroine do not lip-sync the words. Your observation is absolutely correct.

NMK: What’s more, Hindi films seem increasingly to rely on a narrator’s voice-over. It provides information, creates narrative bridges, explains the context, eliminates explanatory scenes and sometimes even tells you the emotional state of the characters.

But if we believe the song is the emotional expression of the character, then the voice-over is doing the job of the song. I feel the use of the narrator’s voice is a primary reason that the song is becoming redundant in Indian cinema. What we are left with are these big dance numbers that are useful to publicize the release of the film and which end up underscoring the end roller.

G: You’re right. It is the narrator that articulates the character’s inner expression now. But you have to go with the times.

NMK: I agree. Though I believe songs and the use of music make Indian cinema unique—they are the glue that keeps us attached to Hindi films.

To conclude this fascinating discussion, which could go on for days, I was thinking it would be most interesting to talk about metre and rhythm through your song “Tujhse naaraaz nahin zindagi”. This lovely song is an RD Burman composition from the 1983 film Masoom.

I wonder what other words could have worked on the same metre.

G [pausing and counting]: “Tujh-se naar-aaz nahin zind-agi hai-raan hoon main.” Now, this is the metre—you count it. How many beats? Eleven. On the same metre you could have had “Jeena dushwaar hai zindagi aasaan nahin hai’ [Living is difficult, life is not easy].

Read More:

Manto in our Times- An Interview with Nandita Das

If Urdu Is Dying I Would Love to Die The Same Way: RIP Tom Alter