Introduction

Mother India (1957) completes sixty years this year. Produced and directed by Mehboob, famous for his social agenda films packaged with a lot of chutzpah, grandeur and melodrama, the film was assessed among the ten biggest hits in Indian cinema in the 20th century. Seventeen years into the 21st century and its memories remain archived in the minds of those who watched the film sixty years ago and those who are watching it now as a flashback not into Indian cinema as it used to be in the past, but to look at and share slices of life among farmers and peasants of rural India of that time. Since cinema is an audio-visual medium, it had and still holds greater appeal for the masses than the written word. This has to be taken against the backdrop of the literacy rate that grew from 18.33 per cent in 1951, to 28.30 per cent in 1961. This is a pointer to the mass appeal of a film like Mother India that underlined the basic economic and social system of rural India where poverty ruled high within the contextual ambience of the strong control of patriarchy.

This marks the 60th year of the release of Mother India, one of the ten biggest box office hits in Indian cinema in the 20th century. Within this context, some readings, old and new, of this unusual yet very mainstream film call for a brief look into the background of its maker, Mehboob Khan, whose life story appears as if it is walking out of a mainstream film script.

Mehboob Khan

Mehboob Khan (1906 – 1964) rose from extremely impoverished origins as an underpaid, “invisible” junior artiste and went on to become a classic filmmaker in Indian cinema for all time. He ran away when he was 16 from Sarar, a small village in Gujarat, to become an actor in the Bombay film industry. His name, origins, career, and history found place in S. Lal’s 50 Magnificent Indians of the 20th Century (Jaico, 2011) among stalwarts ranging from Rabindranath Tagore to Swami Vivekananda to Mahatma Gandhi. His first film as director, a costume drama called Al Hilal (1935), flopped but it gave him the impetus to go on and direct more films. His next film, Ek Hi Rasta (1939), produced by Sagar Movietone, established him as a director of merit who could produce commercially successful films with a solid storyline. Other films that dot his filmography are – Humayun, Andaaz, Aan and Amar, each with storylines that were much ahead of their time.

He had the guts to innovate radical stories that espoused the cause of the poor and the marginalised, even though glamour, songs, and music were priorities for the commercial peg that he could not avoid or did not wish to avoid. He did not shirk from introducing newcomers in major roles. This began in Ek Hi Raasta, in which he introduced Sheikh Mukhtar and Yakub, while his next, the path-breaking Aurat (1940), saw the talent of an unknown face, Sardar Akhtar, who made history with her performance. This triggered its modernised, glamorised remake in the form of Mother India in 1957.

Poverty was the one driving force that sustained his patience and his determination to become an actor. His empathy for the poor and the downtrodden comes across beautifully in almost all of his films. The packaging was with a lot of glamour as time went on and he rose in the ranks, but the content had an agenda for the marginalised while also showing the path to redemption. Roti (1942) inflicted a blistering attack on capitalism. After the wonderful success of Aan, three of his subsequent films — Amar, Paisa Hi Paisa and Awaaz — flopped miserably. But that did not put him down. In fact, he came back with the big budget Mother India, which he had conceived of making way back in 1952.

Aan was a musical costume drama, often cited as the first Indian film to have been shot in Technicolor. The hero is an ordinary peasant, happily tilling his land, till he is challenged with the taming of a wild horse belonging to the local princess, a vain, rude and arrogant woman who fights every suitor with her aggressiveness and her power. How this poor farmer wins this lady’s heart and tames her is the journey this film takes, with several other sub-plots that. This solid storyline is what turned the film into a box office hit. Nadira, who portrayed the princess, had, heretofore, established herself as a vamp and a negative character in films. Her hard looks, sharp jaw line, and heavy voice were turned around by director Mehboob to suit the character of the aggressive, rude and cruel princess. Dilip Kumar played the peasant hero the princess falls in love with. This is among the few films in post-Independent India that portrays a strong woman who acquires “manly” qualities, behaviour, and attitude only to soften slowly and steadily when love happens. Besides, the princess is the central character in a male-dominated, patriarchal industry. Apart from the lavish mounting, high production values, excellent music, and an ambitious budget, the film was ahead of its time in terms of taking on a strong woman who is later reduced to an ordinary woman by the man she falls in love with.

The Political Backdrop

Mother India was a modernised, much mutated remake of Mehboob’s Aurat, although the basic storyline remained the same. The scale of production was also much lower than it would be in in Mother India. Sardar Akhtar, who portrayed the protagonist torn between her two sons, and also placed in a dilemma between her love for her son and her commitment to her village, did not possess the beauty or the screen image that Nargis commanded. Mehboob’s scripts for the two films were accordingly accommodated to suit the screen images of the two actresses.

Khan’s reworking of the agrarian story shifts the focus and amplifies the allegorical weight of the tale, introducing new themes and adding layers of symbolism. Even the films’ titles reflect this expansion in scope. Aurat is the story of a woman, with perhaps some commentary on the oppressed state of womanhood. Mother India, though, captures within its scope womanhood, motherhood, the Republic itself, and the land in which it is embedded. Khan had planned to release the film on 15 August 1957, the tenth birthday of the Republic; it was meant as a tribute to the nation and an expression of its strength and resilience and promise. Khan chose the title in part to rebut the infamous 1927 book of the same name by the American scholar Katherine Mayo, an anti-independence attack on Indian society and culture. And he buffed the story to better serve that ambitious goal.

So, Mother India had a political context in the aftermath of the Independence of India in 1947. The year 1957 marked the first decade after India’s Independence from British rule. Immediately following Independence, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru announced his idea of socialism and human resource empowerment. At the time of the First Five Year Plan (1951 – 1956), India was challenged by major issues such as (a) the influx of refugees, (b) severe food shortage and (c) mounting inflation. Besides, the nation lacked equilibrium as a consequence of World War II (1939 – 1945) and the Partition of India. Consequently, to agriculture was given the top priority so as to overcome the food crisis and to curb inflation. A country where more than 80% of the total population comprised of farmers, a socialist theme of governance was essential to build the initial steps for future development. Mehboob Khan showed his clear support of the Congress-ruled government of Independent India.

The story of Radha, the central character, is a journey through her multi-layered life — from being a shy young bride decked in bridal attire stepping into the humble village home of Shamu, to evolving into a woman struggling between her biological motherhood duties and the responsibilities that circumstances thrust on her as “surrogate mother” of the village and the district. It coincides with the focus on the poor peasant torn between loans that he/she can never hope to repay and natural calamities like droughts and floods that take a toll on his/her land and bullocks. Mehboob zeroes in on a single woman’s struggle through the myriad problems that dog her life, fos instance, bringing up her boys single-handed in an ambience wrought with the pressures of the debt she has to repay to the evil moneylender Sukhilala. He tries his best to blackmail her to give in to his sexual advances. The film closes on one of the major features of the Plan, that is, “to build economic overheads such as roads, railways, irrigation, power, etc.” Irrigation through the construction of a canal forms the focus of the latter half of the film. The village mother, Radha, is requested by the entire village to inaugurate the canal so that the “the waters may flow freely” and the farmers need not be pressurised by the fear of natural calamities or debts or both.

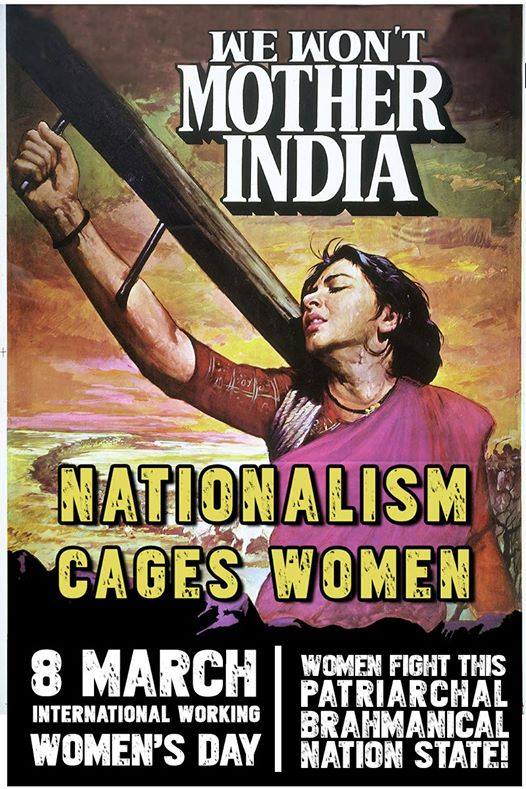

The film holds special significance in terms of the ideal of nationalism as an identity as seen through the prism of a patriotic India which was slowly adjusting itself to the very idea of Independence after 200 years of British rule. The term “Mother India” has been defined as “a common icon for the emergent Indian nation in the early 20th century in both colonialist and nationalist discourse”. The theme of female chastity and honour appears to be an extremely intriguing and engaging topic explored in the film.

When the water begins to actually flow from the newly dug out canal, it is red in colour, symbolising the bloodshed that got the country its independence and the metaphorical ‘blood’ of farmers like Radha that went into the creation of the canal. As the water continues to flow through the rough terrains of the land, like a stream, it slowly loses its redness and turns transparent like clear, natural water, with the soil underneath showing through. The larger goal was to bring attention to the New India, independent India, and to inform the world at large that the nation was now free to embrace the concept of equality and the strategy of using agriculture as the primary way of attaining development.

Much has changed since then, for the worse, so far as the destiny and lifelines of the farmers and their families are concerned. In 2014, the National Crime Records Bureau reported the death of 5650 farmers who took their lives. The highest number of suicides was recorded in 2004 when 18,241 farmers committed suicide. The farmers suicide rate in India has ranged between 1.4 and 1.8 per 100,000 total population over a ten-year period through 2005.

Mother India in 1957

Mother India was the most expensive film made in India within the mainstream Hindi film industry. It also earned the highest returns at the box office among all Hindi films released around that time. Adjusted for inflation, Mother India still ranks among all-time box office hits. The premiere in Delhi marked the presence of both the President and the Prime Minister. It also happens to be the first Indian entry to the Academy Awards for the Best Foreign Language Film, losing by just a single vote in 1958. It notched up several Indian awards in different categories such as Filmfare Best Actress Award for Nargis, the Best Director Award for Mehboob Khan, and the All-India Certificate of Merit for the Best Feature Film. .

Lonely Planet described the film as “perhaps the most compelling film about the role of women in rural India, a moving tale about love, loss and the maternal bond”. In the 1950s, in India, a woman was expected to protect her chastity, especially prior to her marriage. Mother India illustrates how, the protagonist, Radha “stayed true” to this even after her marriage. The sequence set in the bedroom after Radha and her groom, Shamu, just got married portray how valuable chastity is to an Indian woman. The film shows the complete desexualization of the young woman,first married as a young woman, and her extremely passive, coy and introvert role in her intimate encounters with her husband. After he deserts the entire family — when she is pregnant with her fourth child and the third one is little more than an infant — she smoothly shifts to the position of the desexed woman that the ideal Indian mother was expected to be when the film was made, and for several years thereafter.

Ironically, this very desexualisation of the woman once she becomes a mother does not stop the evil Sukhilala from pursuing her relentlessly, holding her to ransom with the loan that has increased over time with the interest that has accrued. Her struggles with poverty and the grief of losing her two little boys, one who is washed away in the flood and the other who dies of starvation, does not take away from her her beauty and her sex appeal, though she does nothing to enhance it and is not even aware of it. Her pair of kangans (bangles), which Sukhilala held as collateral against the loan, carry several meanings and are symbolic of the flux she is caught in — one, as a sign of a married woman who is trapped between not knowing whether her husband is missing or dead; two, she exists as a concrete, physical image of the conventional Indian mother but without knowing whether she is married or a widow or a deserted wife; three, it is one concrete object that finally leads the younger son, Birju, into a life of crime; four, it functions as an invisible bond between mother and son and also becomes the object that terminates this bonding through the death of one for a ‘larger cause’ i.e. the cause of protecting a village girl from being dishonoured; five, it prioritises the nation-mother above the biological mother who must choose between these two – letting her son go, who killed the moneylender in order to retrieve the kangans and give them back to his mother, or, shooting him down. She chooses the latter. Having lost the son, she resurrects her life and her identity as the mother of the nation and extends the limits of the biological mother to become a metaphor for the nation.

This socio-political celluloid essay dotted with spectacle, melodrama, and high hysterics highlighted the role and the plight of an Indian village woman. The film treads on safe the grounds of convention and tradition, just as the social system of the time demanded. The feminist message, if there was one, is now dated and clichéd within conventions, where the virginity of the young unmarried woman turns into chastity after marriage and even after her husband leaves her. It demands a re-reading in terms of the contemporary times we live in and how the role of women, rural or urban, unmarried or married, deserted or widowed, has certainly changed, if not in social acceptance and recognition, then in terms of the perspectives held by these women.

Radha’s story is narrated in flashback. The present — used as a framing device and shown only twice in the entire narrative — could be interpreted as metaphors as well as an attempt to show the metamorphosis in the life and status of Radha. The film opens with villagers pleading with Radha, now an old woman, to bless the inauguration of the village’s new canal. “Arrey, tu to hamari maa hai, saare ganv ki maa,” they appeal to her. The audience therefore, looks expectantly at this interesting character who they now know will not die but will survive despite the blocks and obstacles in her life. She now has an exalted position as the “mother” of the entire village. But at what cost? At the cost of her son’s life, which she brought to an end herself. She did not have a choice in this because it was a decision that was subtly forced on her. Or, perhaps, she was trying to live up to the image of the mother of the village/nation that had emerged over time, as if naturally or through force of circumstance she had no control over? Becoming the mother, of the village/nation, was never in her plans. In fact, nothing was there in her plans except bringing up her two sons the best she could while caught in the most adverse of circumstances. With this carefully thought out framing device, Radha is shown as a woman who has triumphed over adversity but who is no longer in any position to enjoy that triumph. The story never shows Radha pining in self-pity or even in grief when she loses her two little boys. She is never seen blaming her husband, or her destiny, or the virulent moods of nature at any point in the film. She absorbs the tragedies that befall her and tries to overcome them as best as she can i.e. through honest hard work that brings the family some affluence and by trying to bring up her two sons, both of which she fails at.

Mother India – 2017

Mother India remains the classic mother in Indian cinema because it literally celebrated the traditional motif of Indian womanhood in a very different context. The symbol, the moral force of the nation, is shown suffering in independent India, but emerges triumphant in the end as a new kind of ideal Radha establishes it by shooting her own son. Viewed today, Mother India would be little more than a soppy, sentimental melodrama geared to raise the sympathies of a mixed audience.

It led to many different versions of the sacrificing mother in films like Deewar, Kasam Paida Karne Wale Ki, and several others. But none of them could create the iconic value of the nation-mother like Mother India did, and does till today. Although the village — a microcosm for Independent India — venerates her in the end, the real question is whether Radha had a choice in the struggles that she had to go through in her life. We see that she had no choice in marriage and had been conditioned to seek and find happiness with her simple, rustic husband, who was a reasonable, well earning peasant. But his sole interest in his beautiful bride lay in impregnating her again and again and rejoicing each time she delivered a male child. Did she have a choice in conceiving again once a baby was delivered? She did not but she was not aware of this. Her happiness clearly lay, first, in the happiness of her husband, and later, focussed on her sons.

She was pregnant when her crippled husband walks away into the unknown, leaving behind heavy debts that had to be repaid to the evil moneylender. Was she ready for this major catastrophe in her life? “The mother cult has been, from the beginning, one of the strongest thematic strands in Indian cinema, ranging from noble, self-sacrificing mothers to those who pamper their sons and persecute their daughters-in-law….Thematically, Mother India, made in 1957, is one of the most successful as well as one of the most idealistic films in Indian terms.”

Does this brand of idealism stand today? Should it remain the way it was in 1957? “Mehboob Khan visualised Nargis’ character as the Earth mother, an extension of Sita, who is abandoned by her husband and has to rear her sons on her own. Tilling the fields is a man’s role, the woman is forced to do this because of circumstance, not voluntary choice. Yet her virtue and her values remain intact throughout her struggle with deprivation and depravation. By shooting her womb-begotten son at the end to restore justice, she becomes more — not less — of the ideal mother: mother not just of one wayward son, but mother of the entire village, society, and nation. The choice she makes is a difficult one – between maternal love and social duty – and even though it is a gendered portrayal of nationalist ideology, the character rises above the helpless mother stereotype to become a hero: a change-agent.”

Since she had no choice throughout her life, before marriage, after marriage, and after her husband deserts the family, she had neither power nor control over her life at any point. She does her duties because that is what she has been conditioned to do. She is strong but is not empowered. When the villagers approach her in the end of the film, she is white-haired with wrinkles covering her entire face but her bindi intact. She looks up as they approach her, hardly understanding what they are telling her. The honour they bestow on her by asking her to unveil the new canal that will bring in water is something that holds no value for her. Because, inside, she is still lamenting for the son she was forced to gun down. Again, she had no choice. She is helpless and vulnerable to the evil designs of the moneylender. It is her wayward son Birju — a man — who rises in anger against the moneylender, backs her and tries to save her honour, symbolised here by the kangans.

As Sarkar very rightly puts it, “Mother India left behind a problematic legacy for mother-figures in Hindi films, as the crusader aspect gets transferred to the hero/son and the mother is sidelined in her submission and suffering.” Women watching this film are expected to identify with her and the men are supposed to look at her non-sexually and identify her as their own wives or mothers. This initial process of forming a bond with the audience by having clear notions of woman on the street is an important strategy. At different times the film emphasizes on this connection. But should this and does this pertain in the 21st century?

Conclusion

Unlike the all-powerful, omniscient Durga, Radha is as vulnerable to the assaults of destiny as any ordinary woman. Her husband deserts her while she is pregnant with her fourth child and three little ones to look after. She faces the natural calamities of flood and draught, losing two of her four boys to them. She is then chased and assaulted by the moneylender, who rapes her, and she can do almost nothing about it. The retribution comes much later. In the final analysis, Radha does live through all this chaos to see her own triumph of Good over Evil. But she has to kill her own son, Birju, to achieve this. She is a loser in the battle of life in her role as the biological mother because, out of her four sons, only one survives. Ironically, the only son who loved her with a fierce, almost passionate, intensity dies at her own hands. Even after he dies across her shoulders, the camera, in a reverse shot, focusses on his bloodied hands, which slowly open up in death, releasing his mother’s beloved kangans, which the moneylender had held on to all this while.

Even today, Radha offers the Indian audience a sort of a warped role model — not to imitate but, perhaps, to dream about and to idolise. The thumping box-office success of Mother India spewed forth a flood of celluloid imitations with top actresses playing an imitation of Nargis’ Radha. They vied with each other for this role of a lifetime. Smita Patil’s portrayal in two films, Kasam Paida Karne Wale Ki (1984) and Waris (1988) are just two examples of a dozen more cheaper and cruder imitations which could not repeat the success of the original.

There is a tension between the personal and the political, and a continuous process of reconciliation between the two. In the personal, the biological mother is stripped of her sexuality, except in reproduction and in the fulfilment of her husband’s sexual desires. Then there’s the political — the nation-mother — who evolves over the span of the film, intelligently bestowed with a circular narrative structure that ends where it began. Re-reading the film text now, six decades after it was made in 1957, raises questions about the universality of motherhood that has immortalised both Radha and Mother India for all time. “The image of an anguished Radha literally crucified on the cross of Indian virtue eventually evolved into a yoke that female characters in Hindi films had to bear for decades. Sadly, Mother India has been less attractive as the Survivor than as the Sacrificing Woman.”