Once upon a time, Indians were taught to be proud of their country’s linguistic diversity, its long multicultural history, the great profusion of art and architecture, music and dance, painting and sculpture, theatre and poetry, science and mathematics, religion and philosophy – all manner of creativity that has manifested on the subcontinent from the earliest times to the present. The secular Republic of India was pitched as a big tent, under which all kinds of identities, faiths, practices, ideas and beliefs could find space and shelter, coexist, and flourish together.

That era – in place since Independence and apparently quite robust until about three or four years ago – now seems part of a remote and daily-receding memory. The Modi government has attempted to displace, denigrate or destroy traces of all different phases of India’s past, from the ancient to the medieval to the modern. While the Jawaharlal Nehru University and the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library have been targets for a hostile takeover by the BJP administration, the historic Hall of Nations and Nehru Pavilion at the Pragati Maidan exhibition ground in Delhi, designed by the modernist architect Raj Rewal, were simply torn down in April this year. This, despite an outcry from the international architecture and design community, and a legal challenge making its way up the courts over the past several months.

Aurangzeb Road, a major avenue in Lutyens’ New Delhi, was renamed in August 2015, allegedly because Emperor Aurangzeb “Alamgir” (r. 1658-1707 CE), the last of the Great Mughals, was an Islamist despot, a claim disputed rather well in the young historian Audrey Truschke’s recent book, Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth (2017). However, Aurangzeb Lane, a small street off the main road by the same name, remains as it was, again without any explanation or a desire to project consistency on the part of the authorities.

Most recently, within the past week, an extreme right-wing Hindu organization called the Bajrang Sena has demanded that copies of the Kamasutra, a classical Sanskrit treatise about both the physicality and the psychology of carnal love, sexuality, desire, pleasure and erotica, attributed to Vatsyayana and dated to roughly the 3rd century CE, should no longer be sold on the premises of the Khajuraho Temple complex in Chattarpur, Madhya Pradesh. The Khajuraho Hindu and Jain temples, dating to the 10th century Chandela dynasty, carry a profusion of explicit erotic sculptures and bas-reliefs, which are supposed to embody the cosmopolitan zenith of urban (nagara) culture in that region and of that period. Khajuraho is protected by the Archaeological Survey of India and marked as a World Heritage site by UNESCO.

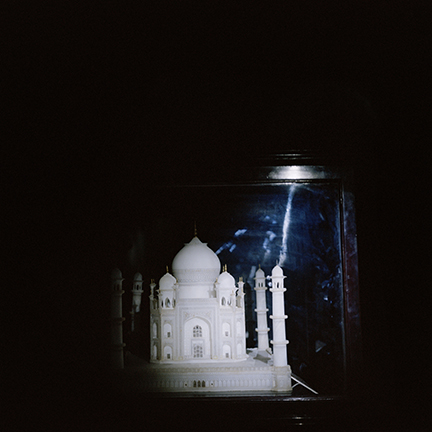

Yogi Adityanath, Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, has announced not long ago that the Taj Mahal, a magnificent white marble mausoleum built by the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan (r. 1628-58 CE) between 1632 and 1653 CE for his dead queen Mumtaz Mahal, is not “Indian”. The Taj Mahal too, like the Khajuraho Temples, is a UNESCO World Heritage structure, in addition to long counting among one of the “seven wonders of the world”. These two sites, together with Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi and the historic city of Vijayanagara in Hampi, Karnataka, probably draw the maximum domestic and international tourists in India. The Yogi said, in a recent speech, that foreign dignitaries visiting the country should be given copies of the Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita as souvenirs, not replicas of the Taj Mahal, which in his view does not represent Indian culture and does not belong in Indian history.

A road. A temple. A text. A tomb. A library. A university. An exhibition hall. An archive. It doesn’t matter what the object or entity: in the Hindu Rashtra, normal and integral parts of our vast complex collective national life are sought to be eliminated all the time. Some are too “Secular”. Others are too “Muslim”. Yet others too “Colonial”. And yet others “Insulting”. None of them is “Hindu” enough – but only in the specific meaning of “Hindu” that corresponds with “Hindutva” and is far away from, possibly the very opposite of what, say, Mahatma Gandhi might have meant by the term.

All nationalism involves some historical sleight of hand, in choosing what to include and what to exclude while constructing a narrative of the nation’s past, and a shape of its essential identity. This is why Rabindranath Tagore rejected nationalism and warned of its dangers, decades before India became a postcolonial nation-state. But Hindu Nationalism – Hindutva – is, after all, Indian nationalism given a sectarian colour, rendered majoritarian. It has all of the blind spots and pathologies of regular nationalism, only magnified and made more threatening to the margins and minorities of the nation.

In this version of rightwing supremacist religious nationalism, Kashmir is an indivisible part of India but the Taj Mahal is not; Khajuraho covered over with erotic carvings is a holy temple but the Kamasutra text sold within its precincts is intolerably scandalous; Aurangzeb Road cannot be brooked but Aurangzeb Lane is fine; Rama is the supreme divine power in the universe, but he was born in a little town in UP where evil Muslim invaders deliberately chose to build a mosque to usurp the god’s earthly birthplace… Let the advance of the great rolling rath, the chariot of the Hindu Rashtra, not be impeded by any stone or impediment of logic, reason or historical fact!

In India we watched with alarm as the Bamiyan Buddhas were obliterated in Afghanistan; as atheist and secular bloggers were assassinated in Bangladesh; as Sufis, Shias and Ahmadis had their people persecuted and their shrines desecrated in Pakistan. We watched with concern but also with an unspoken trust that such things could not really happen in India, where in the end, tolerance, decency and democracy will invariably prevail. Such sanguine faith in the fundamentals of our polity seems increasingly misplaced.

When the government of the day will itself take a sledgehammer to this house that is ours, how long do we expect to live safely within, together in our storied diversity?

Read Ananya Vajpeyi’s interview with writer Kiran Nagarkar here , her note on Eleanor Zelliot here, and her talk on UR Ananthamurthy’s novel Bara here. Read her essay on thinking and counter-thinking through classical texts here.

See Dayanita Singh’s work File Room and read about it here.