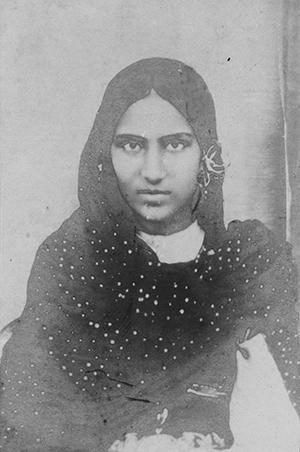

A Most Noble Life: The Biography of Ashrafunnisa Begum (1840–1903) by Muhammadi Begum (1877–1908) (Orient BlackSwan, 2022) is the first complete English translation of Hayat-e Ashraf (1904), the extraordinary story of Ashrafunnisa Begum. Ashrafunnisa, born in a village in Bijnor, Uttar Pradesh, taught herself to read and write in secret, against the wishes of her elders and prevailing norms. She went on to teach and inspire generations of young girls at the Victoria Girls’ School—the first school for girls in Lahore. Her unusual life was written about with great poignancy by Muhammadi Begum—the first woman to edit a journal in Urdu, the weekly Tahzib-i-Niswan. Muhammadi Begum was a prolific writer of fiction and poetry for adults and children, and instructional books for women during her brief life. She aptly titled the biography Hayat-e Ashraf: it echoes the name of her subject, but also means ‘the noblest life’. Indeed, both biographer and subject may be described, says Professor Naim, as ‘noble lives’.

The two women, who met by chance at a wedding, instantly developed a strong mutual affinity, which grew into a lifelong bond. In Ashrafunnisa Begum, Muhammadi Begum saw not only the mother she had lost as a child, but also an inspiring role model who had led a principled life of her own making, and shown amazing grace and strength against grave odds.

This annotated translation by C.M. Naim, an eminent scholar of Urdu literature and culture, also provides the first detailed study of the life and works of its author, Muhammadi Begum, and highlights, in an ‘Afterword’, two key social issues of the time, women’s literacy and widow remarriage, which remain as relevant today.

In this conversation with writer Githa Hariharan, C.M. Naim speaks of the lives and times of Muhammadi Begum and Ashrafunnisa Begum, their work, and the unique friendship that nurtured both of them.

Githa Hariharan (GH): Let me begin with asking you to comment on the ways in which this slim biography of Ashrafunnisa by Muhammadi Begum dispels the gloomy image of the silent and secluded Muslim woman of the nineteenth, and possibly twentieth, century.

CM Naim (CMN): The trouble, as I see it, lies in the ‘totality’ and ‘exclusivity’ we allow to these claims. In the nineteenth century, a huge number of Muslim men are not literate, just as a huge number of Muslim women are not secluded, or not any more secluded than the non-Muslim women of the same class, occupation or region. The wives of Muslim weavers and barbers and food-sellers may have kept their faces covered while toiling alongside men but their lives were not secluded the way we assume it to be – rightly – for the women of the upper classes. Then there were the differences we see in Bibi Ashraf’s life. Her family was Shi’ah; the women of the household held weekly majlis where they read out texts from religious books. She lost her mother when she was only eight, otherwise she would have learnt to read and write the way other girls in the family did. We also see a young Muslim widow, a Pathan, taking up employment with the family as a Qur’an instructress.

GH: I found A Most Notable Life a fascinating entry point into the lives of two women I want to know more about. But I also want to know more about the context of their times and work. Ashrafunnisa’s account of how she learnt to read and write is, for me, the most moving section of the book. She encounters obstacles in learning how to read, but the challenges she faces in learning how to write seem far more severe. I am curious about this. Is it farfetched to conclude that a writing woman presents a greater threat to the patriarchal establishment, because she assumes the power of an ‘inscriber’ rather than merely being a body (or mind) to be inscribed upon?

CMN: The chief obstacles are the wilful grandfather and uncle. The grandfather holds the most authority, and the uncle is more immediately present in the lives of the women in the household. The grandfather is not against female literacy on principle. He willingly allows it until the widowed female teacher gets remarried. That is a worse ‘sin’ in his eyes than reading and writing. But then he considers the fact of his son, Bibi Ashraf’s father, taking up a pesha, a profession –- he moved to Gwalior and became a lawyer — an equal threat to his honour. The family’s attitude toward writing is complex. Her grandfather tolerated some girls in the family learning writing from their mothers; her father rejoiced when he learned that Bibi Ashraf could read and write so well; but her uncle became more furious and punitive. I feel writing in the upper classes, where seclusion was more closely observed, was seen as an instrument that could make it possible for women to break out of that seclusion. We should not assume that writing was then considered an integral element of education. Transmission of essential or requisite knowledge to a majority of males and females could be done orally. Or so, arguably, the society believed at the time.

GH: I am amazed by the use of multiple genres by both women – poetry, essays, memoir, biography, novels, stories for children, ‘instruction’ manuals. Was this characteristic of the ‘educated’ in the times, or was it driven by the need to be useful to a range of readers? And would you say that in the case of women, or these two women at least, the autobiographical element links all the genres they make use of?

CMN: That’s a very interesting question, and I don’t have a clear answer. I can only assert with some confidence that before the twentieth century, most prose writings also contained verses. Very often, these were original verses by the author of the text, alongside quoted verses by well-known or obscure poets. The purpose could have been to emphasize a point by reiteration in a more memorable form, or adding the authority of the past to the point being made. The same is done, for instance, by using proverbs. Nazir Ahmad, the reformist novelist, was a great versifier and public orator. His lectures and long poems at the annual sessions of the organizations he supported were hugely popular. So, anyone who learned to read in those days encountered poetry from day one. And if you had creative impulses, you trained yourself to write verses as well as sentences. In the case of Muhammadi Begum, she was indeed driven by a powerful urge to be useful to other women – her sisters, bahneñ – in particular her contemporaries, i.e. young wives, and girls, and wrote in several genres.

GH: Since the education of women is so crucial in the context of the two women’s lives and work, the writing does a balancing act between the creative and the expression of the self on the one hand, and the didactic on the other. To what extent does such didactic literature – or ‘instructional books’ – differ when authored by men (such as Nazir Ahmad, whose work took up women’s education as well as conduct), and women such as Ashrafunnisa and Muhammadi Begum? My friend, writer and critic Aamer Hussein, writes that “Muhammadi Begum reworks and amends, with affection and insight, the reforms suggested by Nazir Ahmad.” In what ways do the women, Muhammadi in particular, take the project forward, not only as writers, but as journalists, teachers and publishers?

CMN: What we now label ‘didactic fiction’ was not thought of as merely instructional by its authors; they meant it to entertain too. It would have been Khel khel meñ kam ki bateñ, ‘useful words in playtime’. The authors simply called them novels. And this applies to female writers and readers too, until they began to learn English.

As for your core question, I can best answer it by exaggerating my response. Nazir Ahmad, Hali and other male reformists wanted to educate women so that they would be good mothers to their children and proficient in managing their homes. Bibi Ashraf and Muhammadi Begum prize these goals too, but they also prize education as a means of mental and spiritual self-improvement. For better self-expression, even. But the most important thing with Muhammadi Begum is that she lays great emphasis on a commonality of sorts, on a sisterhood of peers. She also wishes to make women proficient beyond her kinfolk, and even beyond the threshold of her own home. To that extent, it may be more the aspiration of an upper-class woman. But it also suggests that for her, female literacy was a given. As indeed it was by that time for the salaried middle-class.

Read an extract from A Most Noble Life.

GH: It’s clear that propriety is the framework within which these two women, and others like them, have to work to reap some gains. Keeping this in mind, may I ask you to unpack the word ‘hayat’ for us? The biography is called Hayat-e Ashraf, and you have translated it as A Most Noble Life. I am thinking of the difference in English between ‘respectable’ and ‘noble’ when I ask you to explain ‘hayat’ for those of us who do not know Urdu.

CMN: ‘Unpacking’ hayat would require explaining what ‘life’ meant to Muhammadi Begum or to an Urdu writer in the nineteenth century – a tall order. I can only say that Muhammadi Begum seems to have chosen the most apt title for her book. It echoes the title of Altaf Husain Hali’s iconic biography of Sir Syed, Hayat-i-Javaid (An Everlasting Life), published only three years earlier. Hayat-i-Ashraf can be read as “The Life of Ashraf[unnisa Begum]” or as “An Ashraf Life,” i.e. “A Most Noble Life.” Ashraf is the superlative of sharif, and the latter, of course, is a marker of numerous presumed personal attributes, ranging from nobility of birth to modesty in speech and much more. Muhammadi Begum organized her book in a similar manner: first, a chronological account, followed by short sections on what she considered her subject’s exemplary traits or, as she put it, her “Disposition, Habits and Manners.” Throughout the text, she never fails to remind her readers – her ‘sisters’ – to exert themselves and follow Bibi Ashraf’s example.

GH: Pioneers have to be remembered not only for what they did – given their times – but also in connection with their descendants. Would you speculate on the ways in which Muhammadi opened doors for the Urdu women writers who came after her in the twentieth century?

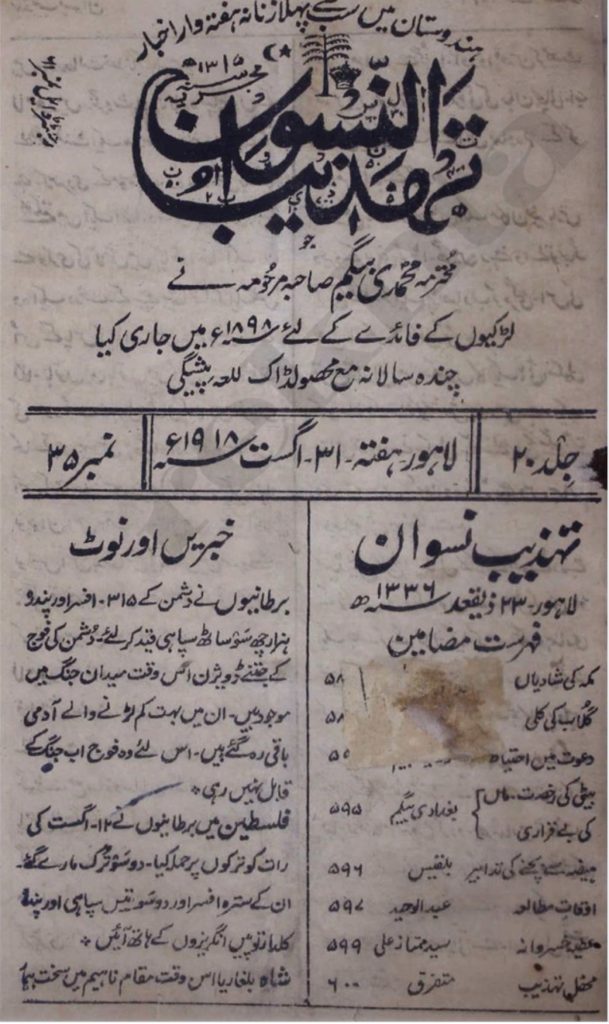

CMN: Muhammadi Begum was not the first woman poet in Urdu, nor the first fiction writer. She was, however, the first in several other ways. She was the first woman to edit an Urdu journal, and to write on many of the issues that were of great concern to women of her community and class. She also wrote ‘manuals’ for women – on writing letters, on managing the household, or on meeting their peers outside the kinship network. In everything she wrote, she made it clear there were no limits to women’s abilities. And most important, she made it clear that women can help each other in discovering, and putting to use, these abilities. I should emphasize one point here. It was her husband’s dream to publish a journal for sharif women that was also edited by a sharif woman – contra the two journals that had appeared earlier and failed . Mumtaz Ali was a champion of Muslim women’s causes, and he strongly believed in gender equality. No doubt he viewed himself as a wise guide, and never hesitated to publish in the journal his own views on some subjects of concern; but what impressed me was his readiness to give space to opposing views, never adopting a patronising or dismissive tone in his responses.

Coming back to your question, Muhammadi Begum’s journal, Tahzib-i-Niswan, gained wide circulation though subscriptions were slow in coming. But it soon became the journal of choice for aspiring female writers. Hijab Imtiaz Ali, Qurratulain Hyder and Rasheed Jahan made their debut in its pages. And Ismat Chughtai made her first appearance in print as an excited reporter from Aligarh informing the ‘Tahzib Sisters’ that Rasheed Jahan had completed her medical course. So I think it is not so much the matter of opening doors that makes Muhammadi Begum’s journal important; it is the spirit of confident sisterhood that she identified and fostered.

GH: I don’t want the two women, Ashrafunnisa and Muhammadi, to get lost in the jungle of history though, whether it is the history of women’s education or journalism or literature. I want to pay a tribute to their friendship – which allowed them to have a rich relationship that encompasses a role model, a colleague and a surrogate family. And this despite their age difference, despite one being Sunni and the other, Shia. Would you say their friendship gives an edge to their interest in writing memoir and biography?

CMN: Their close friendship, their deep trust in each other, was to my mind the most thought-provoking and inspiring thing about them. No doubt, they both had very painful childhoods – having lost mothers at a tender age. But they also seemed to see in each other a kind of partner-in-arms, joined in some cause. The much older Bibi Ashraf unhesitatingly treated Muhammadi Begum, barely out of her teens, almost as her leader in a cause that concerns all women.

We should also recall that the ‘seclusion’ of sharif women in those days was stricter. It even meant seclusion from the company of a great many females within the extended families as well their neighbourhoods. Muhammadi Begum started her journal Tahzib-i-Niswan in 1898, and amazingly, from the very beginning, she thought of it as a gathering place where women, previously strangers to each other, could meet and become ‘sisters’. She coined the expression tahzibi bahnen, ‘Tahzibi Sisters’, to describe this coming together. Then, acutely aware of the larger issue, she quickly proceeded to write a manual on the art of Mulaqat, explaining how a sensible woman should behave in the company of other women outside her own family, complete strangers. It was of course the time when men in government jobs at all levels, including the salariat middle- and lower-middle class jobs, were liable to be transferred from one district to another, requiring their wives to also move from place to place with them. They led a very lonely life unless they made an effort to know their neighbours – strangers or peers – with no past experience to guide them.