In September 2013, a large detail of more than fifty policemen and officials from the National Intelligence Agency raided the house in Delhi where Prof G N Saibaba was living with his wife and daughter. The swoop was in aid of investigating a theft at a village called Aheri in the Gadchiroli district of Maharashtra – so claimed the warrant. Nine years later, Prof Saibaba, his family, and we, the public, are yet to learn what had been stolen at Aheri, what led the investigators to him, or what they were seeking to discover at his house. If the motive of the raid was obscure, its conduct was blatantly illegal: the raiding team impounded electronic devices without sealing them first. The family would be raided again, twice, with a more showy outlay of manpower and vehicles. These events set the tone for Saibaba’s abduction in May 2014, when he was ambushed on his way back home from classes, driven to the airport and taken to Maharashtra, without his family being informed. Held in Nagpur Jail since 2014, he was convicted by a court in Gadchiroli and sentenced in 2017 to a life term.

As A S Vasantha Kumari writes in the Introduction, the case against her husband depends on white noise. Armoured vehicles and commandos accompany him to court and hospital, implying that he is a figure of dread – a message amplified by media houses aligned with the government. Saibaba has the right to be shifted to a prison in his hometown, but continues to be held in the notorious ‘anda cell’ of the Nagpur jail. He has developed multiple life-threatening conditions, including a cyst in the brain. Due to a bent spinal cord and stones in the gallbladder and kidneys, he lives with extreme pain in the lower back and hips, and has also twice contracted covid. He has been losing the use of his hands and struggles for weeks to complete a single letter. For years, he was denied the right to receive material in Telugu or write in the language that he and his wife share. Amid this regime of sensory, medical and nutritional deprivation, in 2021 he was terminated from employment by Ram Lal Anand College. That year, he was also denied permission to attend his mother’s funeral – the pandemic, when prisons were meant to be decongested, was cited as the reason he couldn’t be released temporarily.

On May 10 this year, the jail authorities placed a camera directly outside his cell, depriving him of dignity and privacy even in the bathing area and toilet. In protest he has announced his intention of going on a hunger fast.

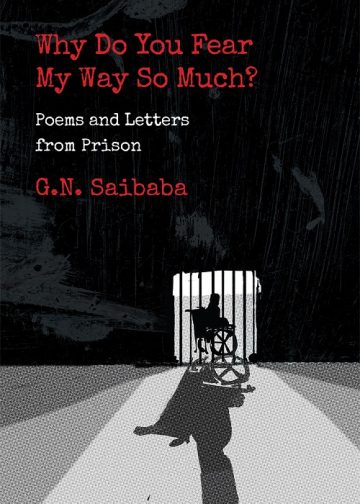

In Why Do You Fear My Way So Much? we meet G N Saibaba as his intimates know him. We see here a student who did not allow childhood polio to come in the way of his ambition, and went on to top his district in the tenth grade. A man who married his friend from childhood. A teacher who lived for his classes, for conversation and reading, and somehow even found money to help financially weak students. A proud man who would use the wheelchair provided by his college during work hours, but could not afford one of his own till 2008, instead steering himself around by his arms when he was back home, his hands stuck into a pair of slippers.

The poems gathered in this volume left his cell as letters written in prose, since the jail authorities would permit written communication only in paragraphs.

A Delirious Dream

I had a dream

as the delirious virulence

of the virus shook me.

I failed in mathematics

in the Second Year Intermediate.

Now what to do

with my MA, PGDTE and Ph.D

or even with my BA?

Do they still stand,

or get cancelled automatically?

I was gripped by the intensity

of the microbe’s attack in my throat.

We were still in our home town

My little brother thrust a letter

from you in my hand

It read: ‘Forget me;

let’s not continue this relationship’.

Sweat flowed down my spine

drenching my prison clothes.

The next day,

in my next moment

of delirium,

I stopped you at the college gate

pillion-driving Murthy’s cycle;

You turned your face away saying:

‘I don’t want to talk to you’.

I was shell-shocked

under the pathogen’s war on

each of my limbs.

Tens of thousands of people

turned up in our city of love

for a right to livelihood.

The police came with a sheaf of papers

The order stated:

‘Permission is not granted

to the rally and public meeting’.

What to do with the sea of people

already in communion?

Does the order still stand?

My feverish body

shivered in pain and anxiety.

Your words on the prison phone

the other day started ringing

in my head again and again:

‘An exodus of migrant workers

has been walking back to their villages,

hundreds of miles away’.

Shockingly,

the attack of the virulent

bug flew away with

your voice vibrating in my mind.

*Wishing you all those days of love and freedom back soon into your evergreen smiling face.

25 July 2021

(Written to Vasantha)

Go Shouting Aloud in the Streets

O friends,

the hearts of my heart!

When so much of love is

deeply hidden in your hearts,

why don’t you break

your silence at this

moment of crisis?

Why do you lose

all momentous times

every time?

If such a burden

weighs down your eyelids,

why don’t you sing

of love this dark night?

This isn’t the time to sleep.

Listen to me, my friends,

Kabir always says,

To declare your love,

you should go shouting

aloud in the open streets.

4 July 2019

(Written to Varalakshmi)

The Way to the City of Love

O sisters and brothers,

My fellow wayfarers,

Why are you treading

this weary path?

If you don’t know the way

to the city of love,

how’ll you reach it?

It’s not enough

to have the desire to go there.

My companions, no doubt,

there are dozens of highways

But don’t deceive yourselves with the idea

that every path leads to the city of love.

Kabir, the servant of love, says,

The city of love

isn’t on the far-off shores

All true lovers find it

in the villages of their heart’s vicinity.

20 October 2019

(Written to Rajendrababu)

From a World of Forbidden Things

I breathe hard

fluttering my lungs

in a world shorn of love.

Banished for life

from my life away

from the beautiful people

I love and cling to

like the ones who flock

at your Jannat Guest House.

I am cursed to live

in a hell of forbidden things.

To talk to my love,

to my daughter, mother

or brother without a meshed wire,

a fibreglass screen,

and a pair of surveilling ears

in-between—

forbidden.

To seal a letter to post

or to receive a sealed envelope

from my loved ones;

to speak, read or write

in my mother tongue;

and to read uncensored books,

letters or newspapers—

forbidden.

To switch off lights

before going to bed

where there is none,

to turn on music

where there is no rhythm in life—

forbidden.

To attend to the calls of nature,

brush your teeth or bathe,

and change your clothes

without a pair of eyes watching—

forbidden.

To see your face in a mirror;

to talk to ants, prison birds,

ghosts of people who died within the four walls

or to fallen leaves brought by a stray wind—

forbidden.

To pour out the burden

of your heart to someone close;

to express a feeling of your

hunger, anger or pain;

or to share a dream

you have had last night—

forbidden.

To smell the cheeks

of your child;

to care for the nape

of your love’s neck, and

to shake the warm hands of a friend—

forbidden.

This winter,

a sweater with green

stripes of affection

brought by my daughter;

a white shirt with tiny spots

of red brought by my love—

forbidden.

I am told

I should only wear white clothes

spun on Hell’s looms

like a Hindu widow

forbidden to touch the colours of life.

After all, the sentence is rigorous,

albeit without evidence,

under the holy laws of national security.

You are reminded

time and again:

You aren’t like all other captives.

*This letter was written long ago, on 22nd November 2017. It seems to have never reached you. I am sending it again now with a hope that it will reach you this time.

22 November 2017

(Written to Anjum, a character in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, a novel by Arundhati Roy.)