Writing for children is no candy floss business. It does not merely involve, as some people think, a simple story line, the use of small, digestible words and a galaxy of ‘moral’ values. That mindset produces ‘cute story books’ which parents feel are safe for children to read once their exams or tests are over and their studies are all done.

But just as too much sugar is bad for children to eat, it is equally bad for their minds. Children are made of sterner stuff. They are very aware of what is happening around them, they are observant, they are perceptive. They are also very conscious of power play in their world, of politics.

They may not have the vocabulary to express what they see and think and feel, but surely that does not mean that they do not know.

A sense of injustice, of being rejected, is a feeling that children learn early. “Mummy likes him more than me.” Or “she is a teacher’s pet.” Or “He is a cheater, cheater, pumpkin eater.” These are words we have heard often from very young children. Relationships between siblings, friendships at school, interactions with relatives – these are all seen as fragile, often tenuous. A child psychiatrist in a Canadian school once told me that the best gift that we, Indian parents, give to our children, is a stable marriage, a secure home. “Indian children can be pretty sure that both their parents will be around,” he said.

There is indeed uncertainty about some marriages now in urban India. But even stability, where it exists, need not be boring or claustrophobic, as it often is. Parents and teachers must allow young people to expand their minds, not through school texts alone, but through music and art, through theatre, through reading. As for moral values, they come in lightly, subtly, through the narrative. At the end, the character who emerges as the most favoured, often after trials and tears, is the one who plays fair.

In fact, for a children’s’ writer, the greatest challenge is not the “safety” of the narrative; it is to be aware of the age group one is addressing. A child of five is not the same as a child of eight, who again is different from a youngster of eleven, again very dissimilar from a young adult of fourteen. And every age group deserves to be introduced to the wonders of our planet and the beauty of language.

How can this aesthetic be reconciled with the reality of what children find around them? Should we pretend that the ugliness does not exist, that there is, for example, no COVID virus, with the isolation, the seclusion, the devastation it can bring? That would be lying, and one must never, never lie to a child.

There can perhaps be a reconciling. One just needs to think it through. While telling a story to a five year old, it should be easy, for example, to bring in the everyday miracle of the sun rising and setting in a festival of colour, to draw attention to the beauty of a dewdrop on a green leaf or the velvet darkness of the night. One can use rhyme, the tricks of language, open up the child’s imagination. Most of all, one can make it fun to read.

For children over eight, there is even more one can do, perhaps there is a greater challenge. One can gently introduce disagreements between friends, night time fears and anxieties, and yet mend it all at the end with acceptable logic to end the narrative in a wholesome way. And so with every group, the areas of conversation ripple wider till it feels as if there is nothing in the world that cannot be referred to. What thematic difference is there in writing for young adults and grownups? Age categories are absurd at times, what is important is the technique of dealing with the same theme, but approaching it in a different way, so that the narrative is more credible and acceptable to the younger reader.

Probably the most important aspect of writing for children, is that the work should not evoke cynicism or, even worse, a sense of nihilism. There are enormous, compulsive dark areas in the cyber world that are attractive to young people. There is something daring here, a new kind of smart adventure. But they are perilous. Teenagers of course would be scornful of fairy tale endings, but they will certainly accept the potential, indeed the glorious possibilities of music, art, sport, literature and science in achieving self-esteem, in reclaiming our planet, in rejuvenating our environment, in discovering a new galaxy.

Often, possibility is just another word for a sunlit day.

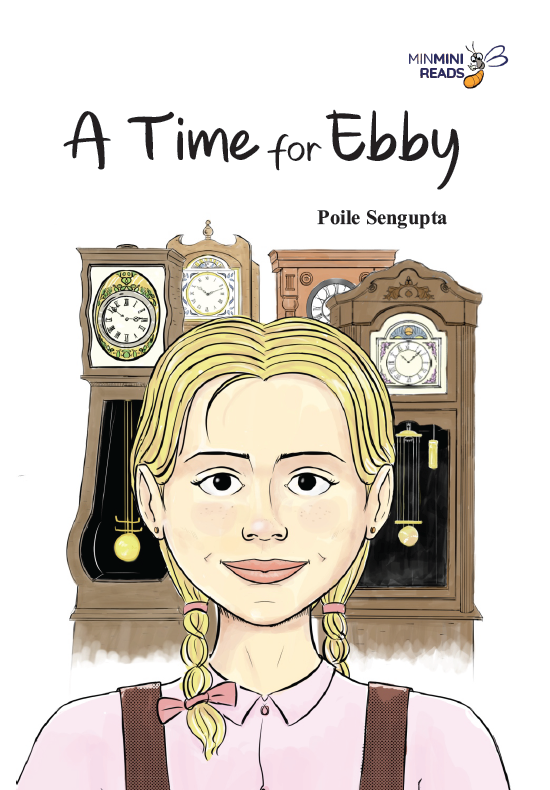

The following is an excerpt from her book A Time for Ebby (2021) published by Karadi Tales.

Father Ebon let his fingers fall away and sat back on his heels, his face once more careworn. Mother Ebon touched his shoulder gently. “Have you looked at the floor of the cabinet?” she asked.

His face lit up and his fingers began exploring again. A moment later, he shouted, “Yes, here it is!” His voice sparked with excitement. “Here it is,” he said again, “Come closer, Mother, my eyes are not what they used to be.”

The light of the torch stilled. In its glow, Ebby saw her parents’ faces, also still, concentrated, like in a painting. And then slowly, they stood up as if waking from a dream, and looked at each other. Their eyes said something Ebby could not understand. Father Eboncame up to Ebby slowly. He took Ebby’s hands in both his own, and in a voice radiant with tenderness, sprinkled with starlight, he said, “Ebby, my child, you will be the next head of the Ebon Family Clockmakers.”

Father Ebon stopped here. Ebby had to wait what seemed a long time for him to speak again. They had to eat first, Mother Ebon was firm about this. Finally, after a delicious supper, the three of them sat around the grandmother clock again.

“Many, many years ago,” Father Ebon began, “my Five Times Great Grandfather Ebon met a stranger, a sailor, who knocked at his door one cold and snowy winter night. The stranger looked extremely ill. Perhaps he was just tired and hungry. Five Times Great Grandfather Ebon was not wealthy then, and it was a very small house that he and Five Times Great Grandmother lived in, but they welcomed the sailor inside, gave him food and a bed, and asked him to stay till he was better. Five Times Great Grandfather and Great Grandmother looked after him so well that the sailor was soon ready to leave and take to the seas again. But before he left, the sailor taught Five Times Great Grandfather Ebon the art of making the best grandfather clocks in the world, and whispered to him two secrets . . .” Father Ebon paused.