India’s decline in the global ranking of press freedom is a much-cited figure. In 2015, Reporters Without Borders had placed India at 136 out of 180 countries; five years later, it slumped to 142, trailing Myanmar by three spots and Afghanistan by twenty. Since shifts in a country’s global position may reflect progress and regress in other countries, this datum does not capture the true scale of the change. To grasp the deterioration of political liberty from within requires a different tapeline, one that has become hard to devise, because in India the independent gathering and verification of information are under stress as never before – to an extent that calls into question the very character of the state.

One way of distinguishing a free press from a state propaganda machine is to see how different a country looks when viewed from outside its domestic media. With a functioning democracy, the divergence should be minimal. This is no longer true of India. Reckonings of state failures have become ideologically inconvenient, even inadmissible – just like the marginalised communities whose condition this data reports. In the bottom third of countries ranked by human development, as also in the gender gap index, India is placed among the weakest performers in the global hunger index, and the environmental index (additionally, it has 21 of the 30 most-polluted cities on the planet). It has been slipping on the corruption perception scale, and is identified with the highest incidence of bribery in Asia. It is, on the other hand, the third-highest military spender in the world, and displays some of its starkest – also fastest-growing – wealth inequality, besides some of the poorest showings in the transfer of wealth via taxes and human-development spending. Together, these figures draw a thumbnail sketch of the health of our democracy. A telling departure from democratic functioning came with the closure of Amnesty International’s India office last year, after relentless harassment by the enforcement directorate, income tax authorities, and a smear campaign by the government. Unsurprisingly, the country has been slipping in the global democracy index: ranked 27 in 2014, 53 in 2020.

The government’s response to unflattering facts is to create an information void. In the past six months alone, it has claimed to have no data on deaths among migrant workers during the lockdown, or among health workers, or on job losses, or farmer suicides – this while tens of millions have fallen into extreme poverty. A free media would have its job cut out to challenge these concealments, but the space for journalism is shrinking, along with civil liberties. And there’s a further complication: with the government being its biggest advertiser and ownership largely in corporate hands, mainstream media has little use for spotlighting the poor or protecting their rights, still less time for others who do so. Mainstream media, as P. Sainath points out, is a misnomer for organisations that systematically overlook 70 per cent of India’s population. Coverage of rural issues makes up on average 0.67 per cent of front-page news in the national dailies, while their middle pages are preoccupied with crime and entertainment, at the expense of social-sector issues (environment, housing, poverty, farming, etc.) He notes that India’s biggest owner of mass media, Mukesh Ambani, is also among the biggest prospective beneficiaries of the new farm laws. Hostile coverage of the ongoing farmers’ protests is a given.

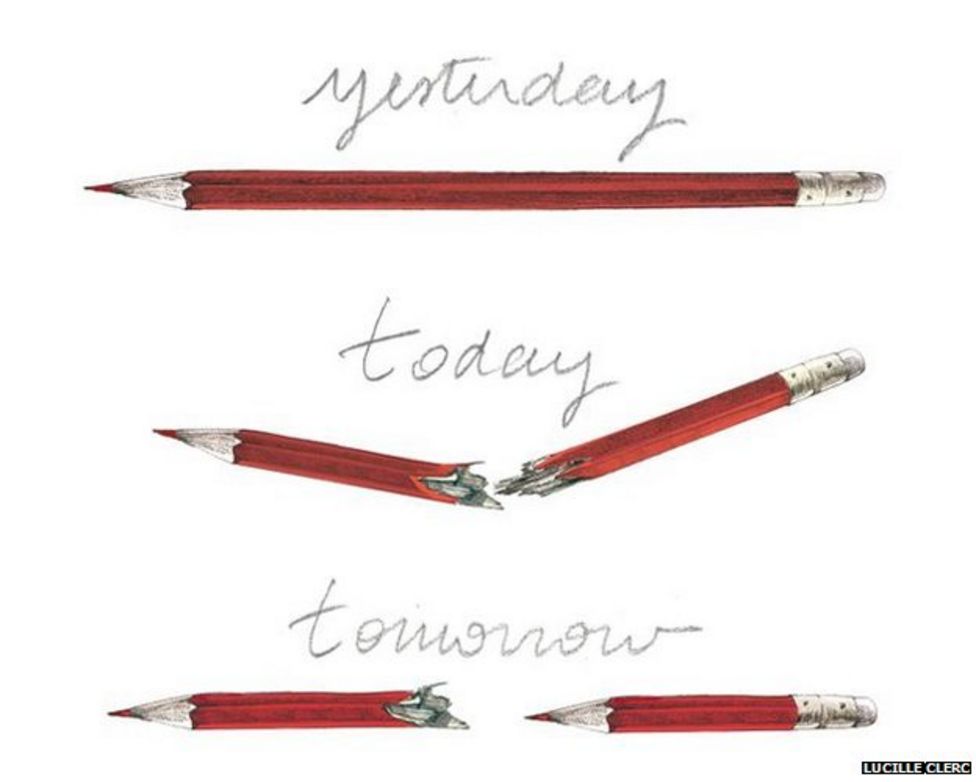

Elitism and cronyism would have been business as usual in a country where the parliament is a showcase of wealth and being a legislator ensures wealth appreciation even in economic downturns, but what is now unfolding is much grimmer. Those who speak up for the marginalised, whether as lawyers, academics, human rights activists or journalists, are treated as enemies of the state. To characterise their position as mere dissent is lazy, since the ‘offence’ is not their criticism of the government so much as standing up for constitutional guarantees and procedures. They are defending the constitution against active sabotage by the state. If the public profile of those being vilified and imprisoned betrays what is underway, so does the lawlessness and impunity of the state’s conduct. Independent journalists find themselves in a tricky position, always at risk of turning into the very victims of abuse whose stories they seek to publicise. The Free Speech Collective’s report “Behind Bars” reveals that over the last decade 154 journalists were arrested, interrogated or served show-cause notices for their professional work, 67 of these in 2020 alone. Article 14 has set up a database on sedition cases, which shows a 28 per cent increase each year since 2014.

The government’s actions over these past seven years have not only grown increasingly authoritarian but divorced from any gains other than an increase of its arbitrary power. For instance, India restricted internet access more than any other country in 2020, and over half the global economic cost of such shutdowns was suffered by India alone. Which places the government’s house-trained media outfits in a curious predicament: trumpeting successes from these years isn’t easy. They cannot take the line that the new farm laws are as sound as demonetisation, as transparent as the PM-Cares Fund and the electoral bonds scheme, as humane and far-sighted as the Covid lockdown, as well-planned as the GST and the Swachh Bharat campaign, or that they will generate the kind of employment and income-security that have been flowing in with privatisation. When the economy is stunned from blow after self-inflicted body blow, institutions have given up any pretence to professional dignity or rectitude, and the constitution counts for little more than the sum of its repressive provisions, jollying the public into seeing a new dawn can be uphill work. Rousing them to a fury is more doable, whether against the dietary preferences and love lives of others (stigmatised as jihad), their struggle for rights (urban naxalism, tukde-tukde gang), their civil protest (Pakistani, Khalistani, andolan jeevi).

On Monday, February 8, came the announcement that The Caravan had received the Louis M. Lyons Award for Conscience and Integrity in Journalism. The same day, its publishers and executive editor were pleading in the supreme court for the dismissal of several sedition cases against them. It was also the day Narendra Modi and Joe Biden had their first telephone call since the president’s inauguration. They spoke, Modi revealed, of their commitment “to a rules-based international order”; and “strengthening democracy at home and abroad”, added the White House press communiqué. The next morning, the enforcement directorate began multiple raids against Newsclick. Its editor-in-chief and his partner were detained at their house, where the raid continued for 113 hours – in contravention of the Patna high court’s 2013 ruling that tax raids cannot go on beyond 36 hours. While Newsclick’s lawyers were not allowed access to their clients and the ED is yet to make an official statement on what it was looking for, sections of the media carried leaks intended to damage Newsclick’s reputation.

Can India sustain its abstraction from reality very much longer? Courageous journalists, among others, will insist on revealing facts and examining evidence. For the rest of us, there’s a new show in town: The Diabolical Case of Greta Thunberg, Disha Ravi and the Great International ‘Toolkit Conspiracy’ (details here and here). Also, should you be interested, the ministry of home affairs is inviting ‘Good Samaritans’ to become cyber volunteers and report their fellow citizens to the state. Once Amit Shah’s ministry has satisfied itself that someone is a menace to law and order, that person or organisation may even lose their access to the internet. Establishing innocence and restoring rights are likely to take, as with sedition cases and the UAPA, a good few years in the courts.