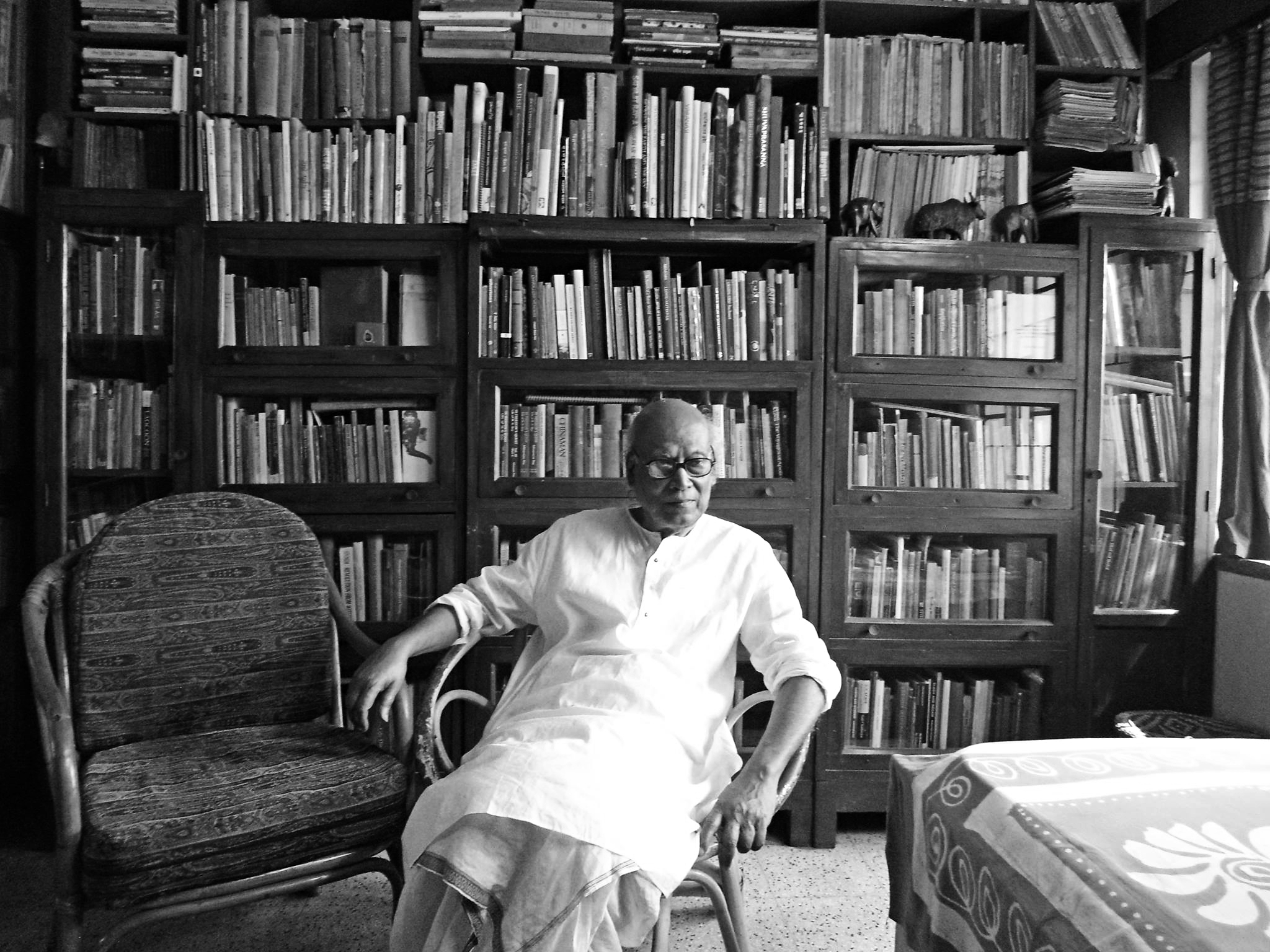

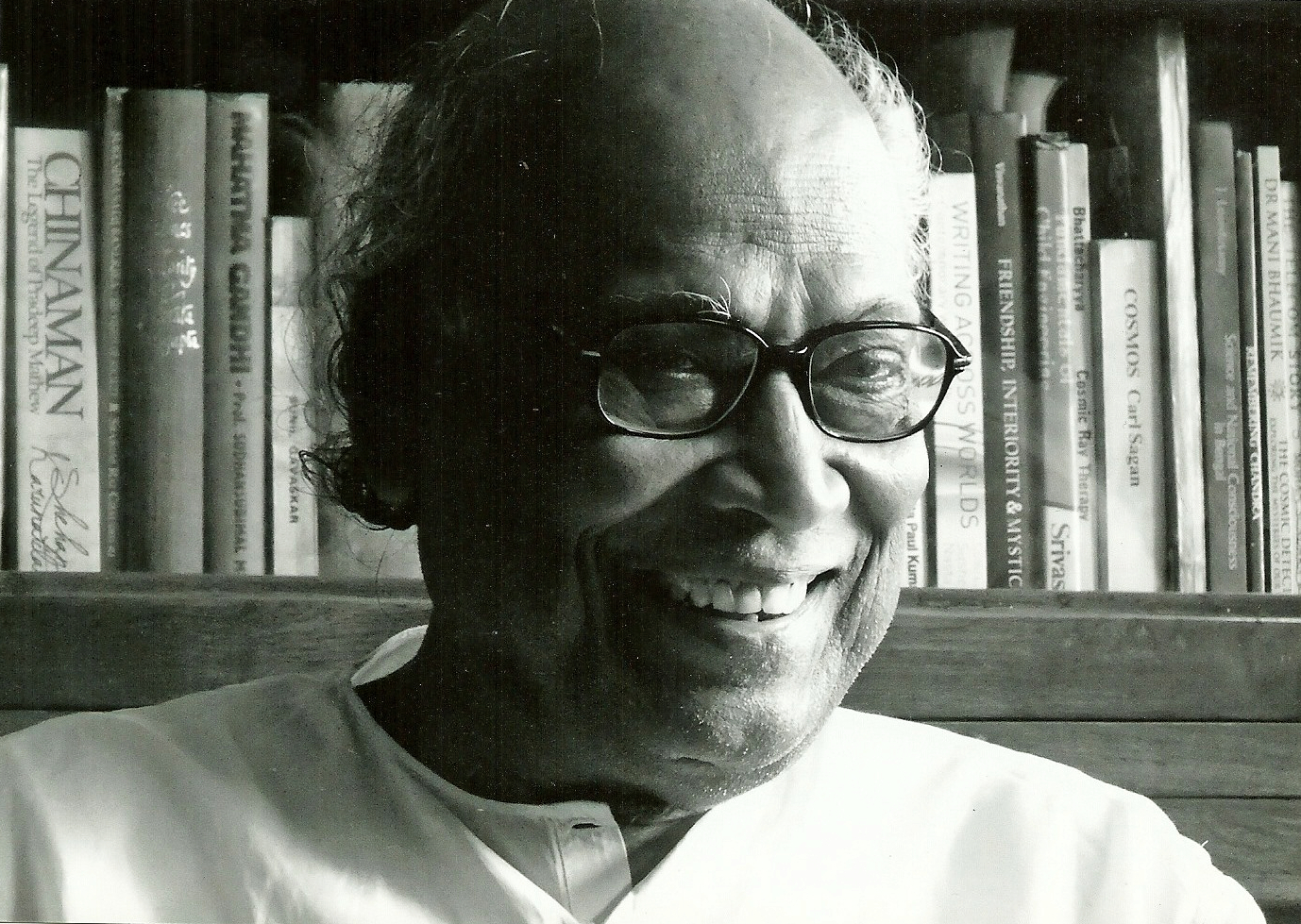

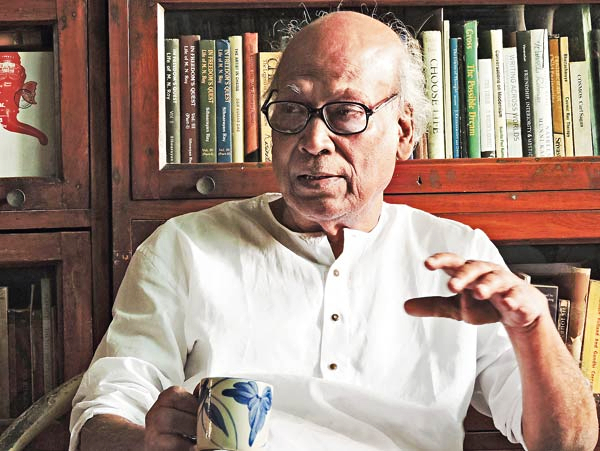

Sankha Ghosh is a poet of suggestions and subtleties. Seldom strident or flamboyant like his contemporaries, his poems, though always filtered and moderated by a sharp intellect that distinguishes him from the romantic crowd, are essentially lyrical poems of moods and feelings.

He is not a narrative poet either, though at times his poems tend to have narrative contexts, questions, conversations and colloquial expressions. It is difficult to compare him with any of his contemporaries, or those who lived and wrote before or after him. He modernised Tagore’s legacy by distilling his style; he could be imagistic like Jibanananda, but is rarely nostalgic like him; he could surprise like Shakti, but is more moderate. It is likely that he learnt from the French symbolists, but the impact is oblique. He never stands out from the crowd like poets with an imagined aura around their heads and he wears even his formidable scholarship rather lightly. Though our exchanges have been infrequent and modest, I have held him in great reverence as a fine poet and a man of unsullied integrity ever since I first met him decades ago in Bhopal. I cannot comment on his poetry with any authority since I am no Bangla scholar, but we do speak about many European writers and even write dissertations on them just by reading their often inadequate translations. This is perhaps the sole justification for this pardonable act of heresy.

The two primary qualities I look for in poetry are freshness of image and metaphor, and an element of surprise created more by the syntax and structure than the subject and theme. No poem of Shankha has disappointed me on both counts. I love the tentative, inconclusive nature of his poetry that is free of assertions that many contemporary poets are fond of; there is nothing crude about his poems; he works on language like a sculptor and is never tired of chiselling his lines to possible perfection. He has kept his range deliberately limited. You may not find the abundance and variety that T S Eliot saw as the first two signs of great poets but he certainly has the third quality in plenty: competence. He is experimental in his own unique way but is too timid to tread the perilous peripheries like some avant-garde post-modernists dare to do — and if that is being traditional, then yes, he is traditional in his understanding of the art of poetry and turns it into his strength unlike the successful mimics of some set traditions.

In his poem, “The House”, the poet says he has always had a house in his mind, but is now looking for one in the real world outside. He fears he may soon be swept along by “the water of light”. It is the anxiety about death, that the poet sees as a dissolution in the eternal flow of the radiance of existence, that lends immediacy to his concern for a solid house that is more than imagined. Solidity and fluidity are presented here in their dialectical relationship.

A similar magic happens in the poem “Love”, where the girl adorns her lover’s body with a bark by speaking about love and he in return fills her flesh with fire. The poet does not use the words “wildfire” or “death” anywhere, but by sheer association, the lines evoke the image of a tree on fire and of death, where the wood and the flesh meet to light a fire in Time.

“Canal”, a poem about love and separation again, uses water and its intricate incarnations and associated objects, and animals to present a complex state of mind — river, wrecked boat, dolphins, canals. The melancholy is tempered by time where face-to-face encounters give way to marginal memories.

In poems like “Puppet Dance” and “Richard”, the poet moves out of the claustrophobic space the earlier poems occupy and begins to meditate on the issues of freedom, equality and determination. I do not know enough to say for sure that this was his way of being a voice of resistance along with the many voices that came up in the 70s, but the voice of resistance, even if subdued by his personal aesthetic, is unmistakable. The poet does not want to dance following the movements of the puppeteer’s deft fingers or produce poems to order. “I moved on so none could ever buy me” he writes, but now a dirty hand seems to be trying to turn him into a primitive. “The dirty hand” may be the hand of some kind of power with blood on it. He refuses to jump into the death-well of servitude.

“A Letter to a Black Friend” expresses empathy by describing the difficulty to empathise: a distance that will forever keep the black man in the realm of the anonymous. Richard is not the poet’s word, dream or sorrow. It takes a real truth-teller to say how hard it is to identify with suffering, while a pretender can easily put up a show of sympathy and protest.

This racial question returns in poems like “Black and White”, where a big black man cries out that his wife is White, thus shattering the whole logic of colour. “The Face is hidden by the Hoardings” is a sharp critique of our time when commerce rules over us and the hoardings on the road hides even the lover from the beloved. The market’s dry logic enters even the most intimate of our feelings; the face is concealed by the advertisement while the mask alone hangs from the hoarding.

In a discreet sense, “The Funeral Pyre” does the same. The onlookers want the pyre to be lit fast so that they can retire to their old complacent selves, while the dead want the Chandal to show him his ash-ridden dance, his tandav on the banks of Ganga. In “Dharma”, it is the unknown necklace of skulls the Void wears that drops Dharma on the dead man’s cold body.

The funeral pyre comes back in a later poem, “The Lotus-Heart”, which has gained a new relevance today as people praise the light rather than see the fire in the funeral pyre which our country has become. We seldom realise the darkness in the rhythm; we carry corpses around and what we see before us is not just the piece of our own mirror, but the sharp glass-pieces that have pierced many bodies. The society goes on drawing circles around the individuals, and the circles get smaller and smaller every time it is redrawn (“So Much Darkness in Rhythm”).

Sankha prefers natural symbols — fire, water, earth, animals, trees — as we have already seen. That is also the case with “The Frog”, where in a house where everything is in place and all looks fine on the surface, a frog dances in the hearts of the couple occupying it.

In “Blood Defect”, the poet points to India that has earned some esteem floating on the map and keeping alive the source of all light, but if a man has still to live on the rice scattered on the road, it must be because he has no English in his blood: the satire here is quite subdued and yet sharp enough to reveal the colonial mindset that we still carry as the source of all our privileges.

Sankha’s concept of poetry is mostly revealed through the poems themselves, but at times he addresses it directly as in “A Poem’s Make-up”:

On most days

the features remain unseen

under the cover of the garrulous face.

Only

sometimes,

back in the room after a bath,

I suddenly see

you in striking make-up.

A poet’s vision often sees a poem remotely and vaguely; only in certain moments of sudden inspiration is it able to capture it in its vivid features. The poem is always there within the poet, but it mostly remains partly or fully concealed.

Connecting the pooja house with the memory of adultery may seem heretical to a believer, but to a lover who wishes to build a bridge to travel to his beloved above the waters of time (note the usual water-time association), her forgetting his village and its pooja house with its drum beating without rhythm — like an ischemic heart — gets associated naturally with the thought of a third who comes in between them, leaving the bridge ever incomplete (Transgression). The twilight glow of blood in the body, as the poet sits in front of the mirror, could well be the ominous feeling of imminent death that creeps unconsciously into the sceptic’s mind (Body).

Good, if it is; no matter if it is not.

Thus indeed,

take life (Being)

This may seem like the calm resignation of a person caught between being and nothingness, but there is more to the poem as it also advises the brooding man to learn something from the calm protest in the eyes of the naked beggar-woman left stranded.

“What Next” is a poem of anxiety that finally leads to an awareness of the meaninglessness of hopes and of existence itself. It is like trying to reach the non-existent core of an onion by going on peeling it. Perhaps the meaning we seek itself is but an illusion. “Foolish, Not Social” expresses an issue we all confront: our cleverness makes us appear intelligent and great on the platform or in company, but once back at home in our solitude we feel like peeling off the face-paint and confronting our solitary, unsocial, stupid self. The boy riding the cow and claiming he is the city’s shepherd when people think he is drunk and want to tie him down pour cold water on his head reverses the city’s logic to re-enact the rural in the urban space.

A similar irony also works beneath a poem like “Bet”, where the ascetic who renounces everything and wins the bet has nowhere to go since he has already cut off all his roots. There is a different dilemma in “Smash My Banner” where before you have time to tell your confronter to shut up and go to hell , that he has no beginning nor end, that he is but water and salt without eyes and nerves, he smashes your banner: our confrontations with others, and even with our own selves, end even before they begin.

‘A Beggar Boy’s Sentiment’ mirrors the poet’s fragile position in the world: he is first asked to sing and then driven away. It is safer to fake, to keep one’s distance and imagine others care for you. ‘Waves within Emptiness’ makes us realise that the mute body is the stoutest of languages and the way of the world is the longest of curtains. Emptiness is many-layered as in the non-corporeal upsurge of the body after death and the long gaze that consumes the low-lying hibiscus by the water. ‘The Tiger’ is a poem of warning: keep even the paper -tiger within the leash as it is after all a tiger even if made of paper. In a sense the poem speaks about the power of the pen and also suggests the reason why rulers of all hues are afraid of writers. In ‘Rehabilitation’ the poet works like a magician who cures a possessed person by nailing down every ghost that has possessed him/ her: predecessors, memories, things, fears, inhibitions, time:

Seated in dim light, the street beggar

Striking two stones of what was and what is

Against each other

Flashes on the everyday rehabilitation.

“Trimeter” is another poem of revelation where the poet and the reader together realise that the sequence of time is strung only on three meters; while others get drunk on liquor, the poet gets drunk on his own inspiration. “Game” points to the state of a man whose game is being keenly watched by all those who have made things difficult for him. The man suddenly feels drowsy between the whistling of the referee and the hoary bantering of the onlookers. This man could well be you or me under the society’s omnipresent gaze or a poet whose stimulus goes dry when the critics expect him to deliver more and better work. ‘What is due to Happen Keeps Happening’ points to the futility of all our protestations despite which the world goes its way impervious to our interventions.

Sankha Ghosh’s poetry beautifully manages to strike a balance between the personal and the social, often with tools drawn from nature, and sticks to the essentially lyrical and the meditative modes even while narratives lie dormant within some of them in the form of suggested individual and social situations. This is poetry straight from the soul, poetry that charms and pains, provokes us into thoughts about the lives we live without ever being loud or shrill.