Prison Diaries (2019), directed by historian Uma Chakravarti, takes us on a journey into the life and death of the late actress and activist Snehalata Reddy, arrested soon after the Indira Gandhi-led Congress government declared the Emergency on June 25, 1975. The film emphasises on how the period had its share of women heroes who stood up for what they believed was right — Snehalata being one of them. Beginning her career as an actress-director and bringing about a revolution of sorts on the Kannada stage and cinema, maintained a diary during her time in prison and Chakravarti’s film is named after it.

The Emergency had suspended all fundamental rights and imposed strict censorship on all media. Subsequently, mass arrests began on the night of 25th June 1975. Resistance to the government and to the Emergency gained momentum and so did the arrests. Socialists and naxalites, among the thousands of others protesting the situation, were targeted, arrested and tortured. Literary writings, magazines and other information circulated through the underground movement were especially active in Bombay, Bangalore and Chennai.

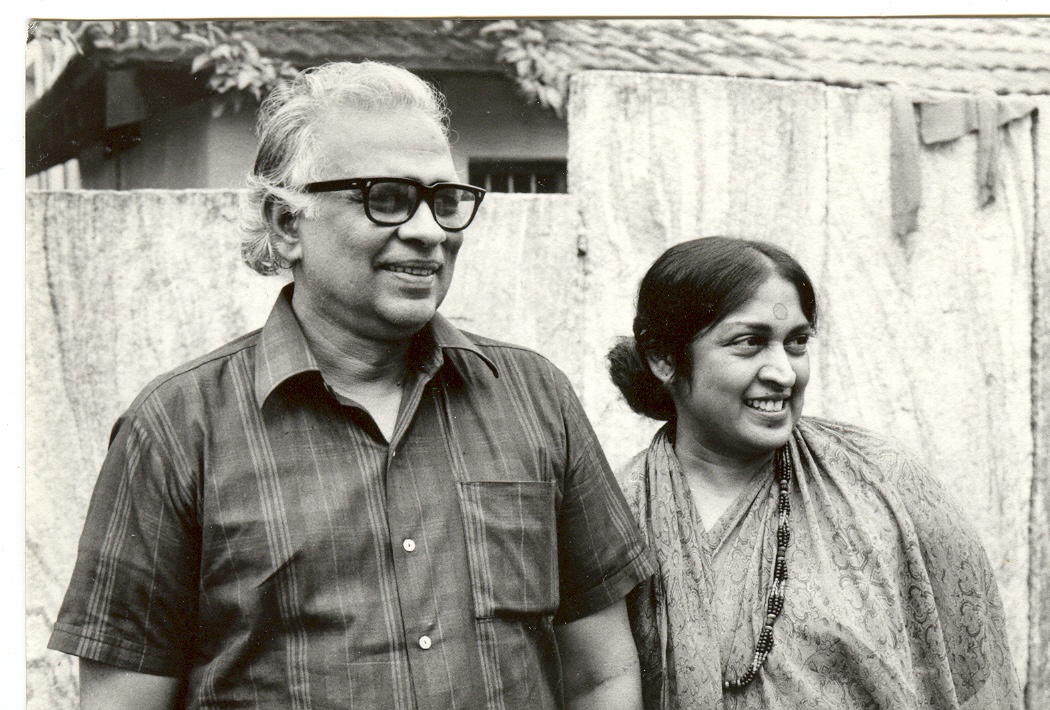

Passionate socialists themselves, Snehalata and her life partner, Pattabhirama Reddy Tikkavarapu, were close to other socialists and trade unionists like George Fernandes and Madhu Limaye, and were also the followers of Ram Manohar Lohia. In 1976, Snehalata was arrested under the MISA (Maintenance of Internal Security Act) — created to quell political dissent and which granted special powers to the police to arrest anyone without a warrant. Suspected to be a part of the Baroda Dynamite case along with George Fernandes, the charge was slapped on her due to mere association. Subsequently, she was locked up at the Bangalore Central Jail for eight months without a trial. No questions could be asked.

Produced by Public Service Broadcasting Trust (PSBT) on a meagre budget of Rs. 5 lakh, Chakravarti’s film is dedicated to Roma Mitra, a social activist herself and a close associate of hers and Lohia’s. The film begins with the audio clip of Indira Gandhi’s proclamation of the Emergency and focuses on Snehalata’s months in prison and on her diary, and offers passing glimpses into her life as an actress, director and even on her chronic asthmatic condition. These are used to juxtapose her days in jail against her earlier career as an actress moving on to her life as an active participant in the underground movement against the Emergency.

In the film, activist Srilatha Swaminathan of the Dehat Mazdoor Union, Mehrauli who was also arrested explains that MISA was termed as “Black Law” which means that the arrest blocks any avenue for the arrested to appeal for bail and must go to jail. The camera then cuts to Barrack E of the Madras Central Jail for 100 prisoners with stills of George Fernandes who was one of the first to have been arrested under MISA and the signature tune of AIR playing on the soundtrack which seamlessly transports you to the time, place and space the film is addressing. Besides this, others who were close to Snehalata during her days as a fiery activist — Amukta Rao, her daughter Nandana Reddy and her son Konark Reddy, filmmaker Deepa Dhanraj — are interviewed by Chakravarti in the film, offering details beyond what is available in the diary.

Historian, academic and filmmaker Chakravarti has written extensively on gender, caste, and class in Indian history. She has also made documentaries on women’s history — among them are A Quiet Entry and Fragments of a Past. Chakravarti’s Ek Inquilab Aur Aya – Lucknow 1920 to 1949, revived the history of two women who lived in Lucknow during the period stated — Sughra Fatema and her niece Khadija Ansari — and their struggles to find their own ways of being in a time of dramatic changes during the freedom struggle, when it was backed by the Left. It is replete with research, old black-and-white photographs, copies of old letters as the film moved through the streets, gardens and by lanes of old Lucknow’s Firangi Mahal.

Prison Diaries too sweeps through beautiful black-and-white stills of Snehalata Reddy as a graceful actress and from their family albums. These include those from her film Samskara (1970), which remains an aesthetically and politically relevant milestone in Kannada cinema. The film is also a daring articulation of caste dynamics in the small village of Durvasapura in the Western Ghats of Karnataka.

The film carries an excerpt from the Baroda Dynamite Conspiracy – the Right to Rebel by CGK Reddy, which says: “When George (Fernandes) made his first secret visit to Bangalore, it were the Pattabhis whom he contacted. Together with Venkataraman, former Joint Secretary of the Socialist Party of India, they were our principal contacts for George’s underground in Bangalore.” However, the film also includes file footage from Anand Patwardhan’s film Prisoners of Conscience which I think is superfluous in a film that can stand on its own.

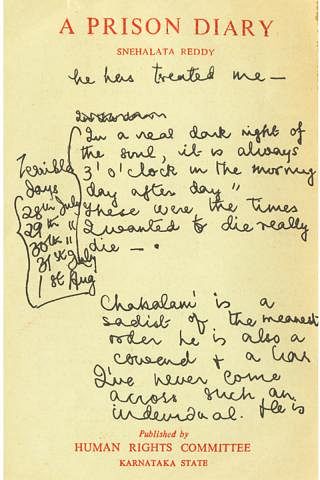

The film also contains excerpts from the diary itself, which was published by the Human Rights Commission of Karnataka State.

“Living in constant surveillance, how do I express this state is violence and you feel helpless?”

“What do you achieve by all these unnecessary harassments? It is a question of deep shame and nothing else”

“My body may suffer humiliation but my spirit – the human spirit – cannot be suppressed for long.”

“I went into blackness half a dozen times till the last time it came gently – faintly – as if an attack was over and I lay exhausted after an injection – but then not even that feeling of floating into oblivion or painlessness just for a moment. How strange that death could be like that…”

Due to high doses of cortisone which affected her asthma, Snehalata went into asthmatic coma. However, under MISA, prisoners were allowed only one visit a week. The film states that her personal doctor, Dr. Pai visited her in December 1976, summoned by the authorities because they were scared that she would die in jail. So, she was released on parole for a month. As the time to come back came nearer, her depression settled back. On her last day in jail, a fellow MISA prisoner just released, came to inform her that she was freed. No one had the faintest clue that during her months in jail, she had become a heart patient. She would repeatedly listen to the song that went “I wish I was.” Sneha died of a heart attack on January 20 1977. In an unexpected move, Gandhi declared elections on January 18, 1977.

The film raises questions about whether the technique and aesthetics of cinema should dominate the subject or should it be the other way round. Chakravarti opens up a whole world which enlarges the locus of the diaries written by Snehalata in jail and encompass one of the most significant periods in India’s political and administrative history. The film uses slices of interviews, letters, pages from the diary she wrote, archival photographs, signature tune of the AIR, which present facts without melodrama or sentimentality. It leaves the audience much to learn and get enriched from, without making value judgements.