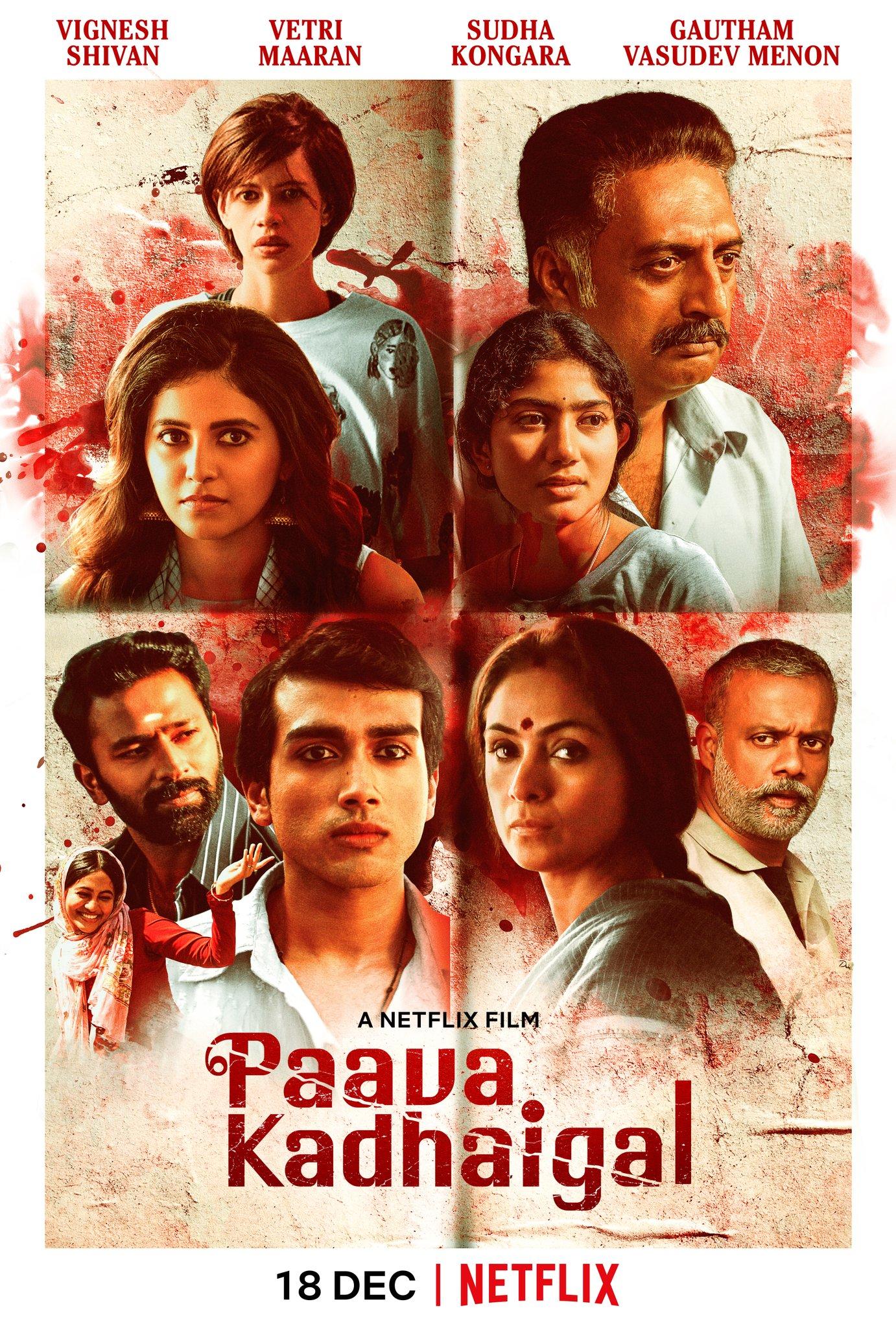

There is a popular adage about saving the best for last. With the new Tamil anthology on Netflix, Paava Kadhaigal, or Sinful Tales, the pick of the bunch happens to be the first short—Sudha Kongara’s Thangam, or My Precious. It works marginally better than the other three films in the mini-series. Kongara reframes the archetypical sentimental love triangle with a Muslim transgender person, Sathar (Kalidas Jayaram), playing the one who loses in love. Their* love for childhood buddy Sarvanan (Shanthanu Bhagyaraj) remains unrequited what with their own sister, Sahira (Bhavani Sre), turning out to be the object of Sarvanan’s affection. The love story becomes a pivot on which to examine prejudices against transgender people. As Sathar puts it, they are either at the receiving end of disgust or are taken advantage of. Even their family would rather have them not exist; genuine, unconditional love never comes their way.

Aside from the very valid debate on why a cisgender had to play Sathar, Jayaram’s affecting performance does make the film sail along for quite a while. Playful, caustic, passionate and vulnerable in turns, his Sathar is also ahead of the times—thinking of and working towards a gender reassignment surgery way back in 1981 in a small town of Kovai [or Coimbatore] district.

Parallel to the hatred directed at Sathar is also the other target of bigotry: the Hindu man marrying a Muslim woman. Despite a sense of doom right till the end—the fearful sight of a knife being sharpened, for instance—this conflict is rather easily resolved. But there is no sign of society showing any remorse or penitence for its sins when it comes to Sathar. The shrill ending becomes entirely about Sarvanan’s sense of guilt as an individual rather than a collective repentance. And this aspect gnaws away at the back of the mind long after the film is over.

The other three shorts distressed me even more. Vetri Maaran’s Oor Eravu, That Night, might be the most well-realised of the lot, cinematically speaking. But the very idea that forms its bedrock, and how the theme has been framed, left me asking more questions than I would have wanted. Pregnant Sumathi (Sai Pallavi) is reunited with her parental family at the behest of her father, Janakiraman (Prakash Raj). He invites her and her husband, Hari, a man from a lower caste with whom she had eloped and lives in Bengaluru, for some rituals akin to a baby shower. Now things take an inconceivable turn; the independent daughter who had built a life for herself loses everything.

There are some beautiful moments strewn all over the film—the father observing his daughter from a distance during a yoga class, the siblings and their parents are seen sharing a meal after a long hiatus. As in his other films, violence is at the crux of Vetri Maaran’s narrative but the unrelenting and unflinching portrayal here—even if supposedly inspired by real events—turns out to be more futile than effective. What does a viewer gain from his portrayal of the prolonged misery and suffering of a woman? Does it create any lasting empathy or does it merely make our stomach churn as events unfold on our screens? The brief moment at the end of Sairat had left a much stronger impact, without laying everything bare, than the one gut-wrenching night of Oor Eravu that occupies most of the screentime and leaves us with a girl begging to die with dignity.

What is more, it is the father who eventually become the focus of the narrative. Though splendid, Prakash Raj towers over everyone else like some flawed Shakespearean tragic hero—not the repository of malevolence that his character essentially is. I certainly did not care to rescue him, by characterising him as misguided, or not. The jury is still out on whether his character gets humanised or mythologised but the niggling question for me is, is an aesthetic recreation of the scene of a crime really an effective way to deal with boundless inhumanity?

The mixed messaging and the father figures get even more troubling in Vignesh Sivan’s Love Panna Uttranum, Let Them Love, and Gautham Menon’s Vaanmagal, Daughters of the Skies.

Sivan’s perplexing film is about a political leader, Veerasimman (Padam Kumar). He propagates ideas of equality and parity among castes while his henchman, Narikutty (Jaffer Sadiq), restores “balance” in society by bumping off couples who marry outside their caste. What happens when the leader’s twin girls—Aadhilakshmi and Jothilakshmi—decide to marry for love?

We may keep arguing on the humanisation of the patriarch in Oor Eravu without arriving at a consensus, but the song of the father in Sivan’s film is an out-and-out and misplaced attempt to generate sympathy for him—“forgive and forget my sins, my child,” it goes—a near-justification for the violence he heaps upon his daughter, and for which he blames “incitement by kith and kin”. Equally abrupt is the father’s change of heart and the quick and easy “all’s well that ends well” finale.

Then there is the tonality. The serious alternates with the farcical and outrageous, but they do not mesh into a potent absurdist universe, one in which even a theme such as honour killing could have been placed under a unique lens. Lesbianism becomes a convenient device, a twist of the plot and also the butt of a terrible joke, not to speak of Penelope (enter, Kalki Koechlin), joining the plot in the role of an “acceptable partner”, a white foreigner of course. Love Panna Uttranum reinforces the very same jaundiced view that it could have destroyed. All that stays with me is the swagger of the vertically-challenged villain and his cuss words. Here is a film that tries to give a wacky spin to a social concern, but remains utterly scattered, confused and pointless.

Gautham Menon’s Vaanmagal felt like the most disingenuous of the entire lot. A close-knit family’s life turns upside down when their youngest daughter is sexually abused. For most of its run-time, the film plays out like a near-endorsement of the traditional, conservative mindset. The prolonged puberty rituals; the talk about girls regarding their bodies as temples and protecting them, about being repositories of family honour, pride and prestige. The whole edifice feels dangerously reactionary, but it is barely ever questioned. Then the director makes a sudden U-turn and tries to bring down orthodoxy in one stroke at the end, when it is too little, too late.

The upholder and perpetrator of all the regressiveness in Vaanmagal is the mother, Mathi (Simran), obsessed as she is with water, washing, cleaning up and purity. Yet, unlike the father of Oor Eravu, she does not get a larger-than-life arc, nor does her mind come out as a purportedly feverish battleground for all the dichotomies within her. It is a disconcertingly flat portrayal.

The father, Sathya (Menon himself) is presented as a well-meaning soul, the one with the moral upper hand and as the wind beneath his daughter’s wings but really if you dig deeper he is quite passive, inert and ineffective.

It is in the brother’s response to the crime that the patriarchal codes play out in full force and get insidiously upheld. A man who believes his “honour” has been slighted because of something that his sister goes through takes a feudal stand and seek vigilante justice. Is this a move away from patriarchy and orthodoxy or hurtling us right back into the problematic fold? The film takes a strangely patronising and consciously righteous gaze which undermines the woman rather than put her at centre-stage. These are our stories, perhaps, but they don’t quite speak to us.