One memorable voice in Second-Hand Time remembers: “On the eve of the 1917 Revolution, Alexander Grin wrote, ‘And the future seems to have stopped standing in its proper place.’ Now, a hundred years later, the future is, once again, not where it ought to be. Our time comes to us second-hand.”

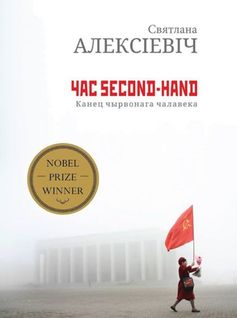

Second-Hand Time. This is the title of Svetlana Alexievich’s magnum opus on “the history of the Russian-Soviet soul”. A history of the soul – or histories in this case – may sound a little pompous, but it isn’t, once we are deep into this book. Its chronicles are replete with varied human detail, personal, revelatory, vivid; and they come to us through an almost endless series of individual voices.

The interviews in this book were conducted between 1991 and 2012, but there’s a more ambitious timeline both on and offstage: from the 1917 Revolution and World War II, the USSR and the Soviet way of life, “Homo Sovieticus” before Stalin and after, to glasnost, perestroika, Russia and the new post-Soviet countries. The past lives because it is embodied in individual memories. For the most part, it is a second-hand re-living of socialism, either without or with a “human face”; or the living of either a “heady” or “feral” capitalism. But memory, whether remote or recent, is not alone on the stage. For a book so full of the past, the present is very much there. By the end, we find ourselves writing a mental afterword of Putin’s Russia today.

The sheer range of this book, its complexity of debate and human experience, makes comment on it daunting. The canvas is almost too large. The book is about the USSR and Russia. But it is also about a large map of abstractions all of us live with, and live by. In this map of colliding ideas that we recognise, very little is black and white. Freedom; ideology in theory and practice; the power of memory, conversation, debate; official history versus a “people’s history”; money; war; and always, the need for a belief system, for meaning, not just in the individual mind, but in the collective. Without grappling with all these, the book seems to say, there is no “homeland”; indeed, there is no intelligent life.

Svetlana Alexievich is aware that a canvas as large as this must be peopled, quite literally, with a spectacular, heterogonous cast if she is to bring alive the Soviet experiment and its dismantling. The book, 570 pages long, is a intricately woven tapestry of people’s voices – one account dissolves into another into another. Sometimes the storytellers are related, mother and daughter, grandfather and grandson, neighbours living practically in each other’s hair. Other times, the stories come from different places and times altogether. Alexievich’s questions are also determined to remain at the individual, human level. “I don’t ask people about socialism, I want to know about love, jealousy, childhood, old age… the myriad sundry details… It’s the only way to chase the catastrophe into the contours of the ordinary and try to tell a story… I look at the world as a writer and not a historian. I am fascinated by people.”

So she turns the canvas into an “emotional” one – where her interviewees’ voices speak of the larger stories, but almost always through small stories – love, families and neighbours, the kindness of strangers and the viciousness of fellow citizens, loss, despair, violence; sacrifice, with meaning still sometimes, empty sometimes. These stories make a textured mosaic with a thousand pieces, all interacting to insist we judge belief systems, and change, only through lived experience.

Every part of the timeline is probed from multiple perspectives so that we are left with a welter of impressions. Soviet life. There’s the grey salami, the faceless grey buildings; the bleach and rag smell of cafeterias; the fear of surveillance and the viciousness of Stalin’s camps; the never-ending quest for the motherland’s glory and the never-ending violence, battles and wars in its service. But there’s also the equally powerful comfort of shared music, education, collective ownership, ideals; the deep pleasure of books and conversation; and the comfort of an orderly life with everyone more or less equal in terms of hard work and hardship. There is, of course, the vast distance in practice between the rulers and the people; but this is nothing compared to the inequalities the movement for a better socialism, or democracy, or “freedom”, brings about.

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev began the first reforms under the umbrella of perestroika and glasnost. Land was restored to peasants after sixty years of collectivised agriculture. Political prisoners were freed; there was a move toward political pluralism and freedom of speech. Troops were withdrawn from Afghanistan. Dissidents such as the nuclear physicist and human rights activist Andrei Sakharov were allowed to return to Moscow. In 1991, high-ranking official attempted a putsch. Thousands of people protested the putsch, with Boris Yeltsin addressing them from atop a tank. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was dissolved. So was the Soviet Union. On December 25, 1991, the Soviet flag was lowered, and the Russian tricolour raised in its place.

Reading about the early nineties recalls for many of us responses around the world. The middle-aged Indian who felt so orphaned he shaved his head: his image, for instance, hangs in the background as we hear still-Soviet Russians recalling depression, staying in bed for eight months, forgetting how to walk.

But for a while, the heady sense of victory continues among those who have joined the protests, dreaming of greater freedom. Most people are wonderstruck by the sudden “plenty” in their midst – nothing grey any longer, so many different types of salami, jeans, vodka, shoes, bags, bras; a paradise consisting almost entirely of a well-stocked supermarket. But these things need to be bought; and it’s every man, woman and child for herself. There’s a new god to be courted, and this god has a terrifying mouth full of teeth. God Money. That old map with the shifting location of freedom grows illegible. All the new unmapped roads lead from the glory and the tyranny of the motherland, to the glory of owning things and the tyranny of acquiring money by any means. The distance between old and young increases. Alexievich says, “I asked everyone I met what ‘freedom’ meant. Fathers and children had very different answers. Those who were born in the USSR and those born after its collapse… it’s like they’re from different planets.” As the new capitalism reveals its feral face, what happens to freedom? “No one had taught us to be free. We had only ever been taught how to die for freedom.” The distance between samizdat, clandestine literature in the Soviet Union, and tamizdat, Russian writings published abroad and smuggled back in the USSR, has been bridged. But freedom, even its definition, remains elusive.

How are people to make sense of two such worlds in a lifetime? For a fifty-seven-year-old doctor, whose cherished childhood memory is of going to the military parade on Red Square on her father’s shoulders, the new Moscow is a foreign country. Everything real to her, Party cards and medals for valour, are now road-side junk, sold as souvenirs to foreigners. Not only is her beloved Moscow lost to her; she has suddenly changed nationality, from Soviet to Russian. Worst of all, she’s “one of the people who’s fallen behind”. In the latest edition of the battle where the Reds are the monsters and the Whites are the knights, she no longer knows who she is.

This sense of loss, of the past, of location, runs through the book like a sad inescapable thread. So pervasive is it, even with awareness of repressions, that there is an obsessive desire to make sense of it all. What happened? Was it a revolution or a counter-revolution? And what is to be done?

What happens is as unbearable as life in the Gulag camps or the endless memories of war and fear. Except this time, there is no glue of a belief that the word, or a motherland, or an ideology, can keep the world intact. Freedom: there are different countries now; Tajiks, Armenians, Chechens, Georgians, Azerbaijanis no longer need to be Soviet. But they have lived together to make their livelihood, their families and beliefs, for generations. Suddenly it is not just White versus Red. It is race, colour, ethnicity, religion. Prejudice, hatred, fear, violence. On the one hand, from the new non-Russians in Moscow: “We live here as though we are at war… Everywhere we go, we’re foreigners… On the other hand, from a Russian: “Life is better now, but it’s also more revolting.”

This piling of oral history, “novel-evidence”, works as “little history”. “This is how I hear and see the world – as a chorus of individual voices and a collage of everyday details,” Alexievich, Nobel Prize winner for 2015, has said. But it is almost too much. When Alexievich, a citizen of Belarus born in Ukraine and writing in Russian, makes a brief, unexpected aside, we want to listen carefully. Often, it is not enough. We long, like the people in the book, to make sense of it all. But we too are left with memories, and a yearning for a freedom that can be lived. All the same, Alexievich achieves this through her writing: though we are neither Soviet nor Russian, it is hard to read Second Hand Time without hearing our voices. Hearing our own questions about how we want to live – either as people or as a nation.

Githa Hariharan has written fiction, essays and columns over the last three decades. Her most recent book is Almost Home: Cities and Other Places. For more on the author and her work, see www.githahariharan.com.