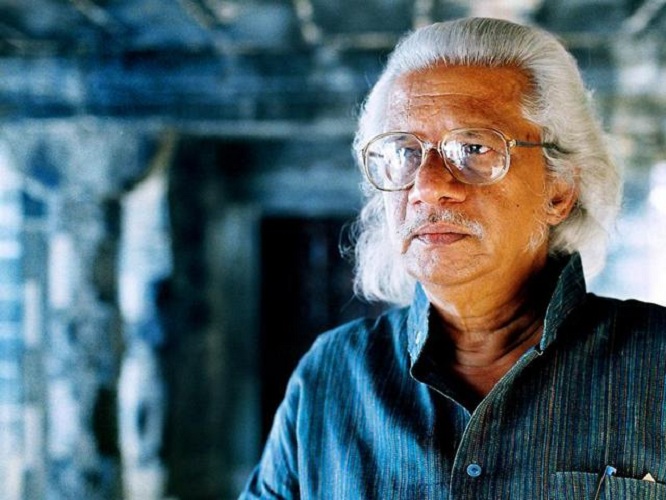

To offer my personal views on Adoor Gopalakrishnan, one of India’s finest filmmakers, a man who is always rooted to the milieu around him, seems like a rather difficult proposition. The moment it is done, I think, a template is provided to stag it.

Since my knowledge of Adoor and his films contains a fraternal and cultural relationship between us, I am made more prudent to do the job and that too with critical ballast. Since his name and fame have traversed the globe, his portrait demands colossal studies and a clinical approach, to be precise.

Before I probe into his works, let me give you a caveat that Adoor Gopalakrishnan, while engaged in making films, does not only copy reality, but also seeks to surpass it. This is why his oeuvre is a big departure from the heavy bulk lying around us and fortifies a concept that memory, per se, is linked with experience. This is a vital clue to understand Adoor and his rich body of work.

Typically, his films visited various film festivals. So, for close to a year after he made a film, he found himself running around from country to country. It was only after all this that he could finally put the latest film out of his mind and find some inner space; find the time to start thinking, even in a vague fashion, about what he wanted to do next. Once he decided that he would take time to do his research, to firm up his ideas, to script it, revise, look for locations, begin shooting, he took a lot of much-needed time to make each film—and rightly so. And he was comfortable with this process, that was how he loved to work. And, therefore, we are comfortable with his method of execution and making of films.

While taking stock of his few difficult films, even by his standards, it appears as if he was unsure about the upshot of painstaking experiments, though he had released Kathapurushan in 1995 and his later film, Nizhalkuthu, only in 2002. It was that kind of subject and it took him researching it longer than usual and he didn’t want to start shooting the film till he was fully satisfied.

Prior to this, his film, Anantaram, seems to be the most difficult work of Adoor we may have ever seen. The more I see the film, the more I am fascinated, and equally haunted, by the image of Ajayan, the brilliant lad, who is shown to gradually lose his original power and imagination due to psychological neurosis making him a victim of his family and the society he lives in. His formative years as a young boy display characteristic intelligence, imagination and introspection. At an early age, Ajayan counts steps up to 39 and back which leaves us stupefied! Can we match Ajayan by any stretch of our imagination and intellect? I, for one, doubt it and wantonly so. Anantaram is arguably one of Adoor’s greatest films, undone as yet by any other Indian filmmaker. In my opinion, it is also Adoor’s most difficult film to date.

It is interesting to know from Adoor how ideas germinate in his mind. For him, ideas do not come from any one place. He hears things, reads about things, observes things and stores them cautiously in his mind and, at some point, these various “things” come together. He still works in such a mode of wonder! This is Adoor’s usual instinctive style of working before he takes a leap into a new film.

For example, only when he was working on Mathilukal, sometime in 1989, did he first begin thinking of making a film on crime and punishment. Much later, he came across a small interview in Malayala Manorama, with a hangman, the last hangman in India. Adoor cut that interview out and saved it in his file. Then, at some point of time, the whole thing began to grow and take shape in his mind. Gradually, imprints of images on the subject seized his imagination, and the kernel for the film was born.

Since his films have always been about issues, subjects, they follow a certain trajectory of his conceived plans.

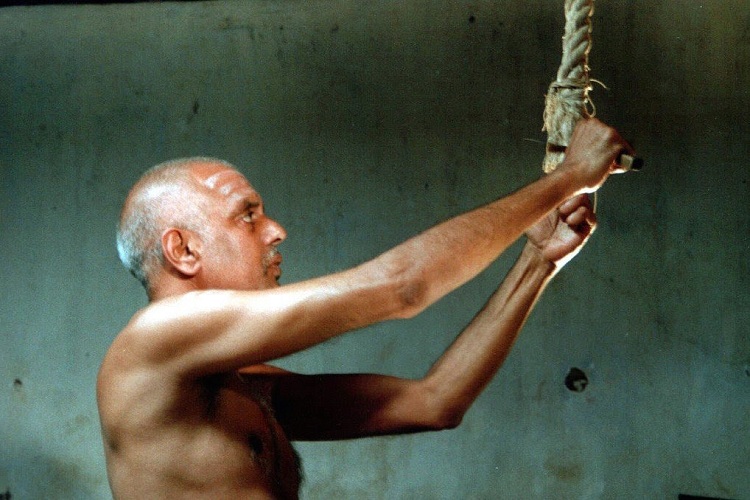

Nizhalkuthu, however, focuses on the person, the hangman, the last one during the British Raj. And curiously enough for Adoor, this was not a deliberate departure from his usual rustling up of a stilted norm. Even Nizhalkuthu was about issues. Maybe it was because his protagonist, Kaliyappan, was such a palpable character, so vivid, and so well-acted, that he loomed large before us and obscured whatever else lay beneath the plot’s surface. Powerful images from the movie still linger in our minds. Such is the impact of Adoor’s works.

In fact, he wanted to make a film about crime and punishment, like he had earlier said, but as he worked on the plot, it became more than that. He later said that as he made it, the film became one about individual and collective responsibility, about sin and redemption, about freedoms, both real and perceived. It was also about his land, Kerala, about him, and the people around him. It was, to an extent, about his personal ecstasy and frustration as a human being. Our cogitation about Adoor’s rolling universe equally fascinates, pampers and enriches our introspections.

Going by a slew of facts, Adoor, though sheer dint of his artistic instinct, has been making films for fifty years, keeping in mind each film’s relevance to the audience of the time. He pretty well knows how to invest his themes with contemporary sensibilities. Probably, his social thinking revolves round his existing surrounding and milieu, a lesson for tackling his universal cinema. However, he explained it was not in the sense that when working on his story, he whispered to himself, “This is my audience and this was how it should be relevant.”

Far from it. If the issues are valid, if his thought is valid and the reasoning behind his story sound, then it would automatically be relevant and valid in ontological terms. And Adoor follows his films with strict fidelity marked by thematic relevance.

Adoor’s characters, it is true, never act with outrageous inconsistency—his sense of probability is too great for that. Neither do they act under irresistible force of their directing principle; this allows them to always remain true to themselves. Through every change of fortune, every variety of circumstances, they remain the same clear recognizable individual moral entities.

Truly, a film is made in its time, but not for its time. A good film, he still believes, will last far longer than the lifespan of its maker. He also believes that like good works of literature or art, the impact of a good film is cumulative over the generations. It takes a long time for that impact to be felt and for it to translate into results. In any case, he feels, he does not make films on every day, ordinary problems or restricted reality. He does not have the energy to invest in such films. Rather, he prefers to focus on larger issues. According to him, the idea of making films is to influence thought and create a space to be within it. He thinks, awareness of an issue is only the beginning. Such a film should disturb you, it should make you ask questions of yourself and of society; and, he emphasizes, questioning is the first, small step towards change and changing mindsets.

In Vidheyan, Adoor’s imagination is certainly the most extraordinary—his mind never applies itself to silly cinema. It is also an imagination appropriate to the internal way of thinking on which he chooses to work. In order for the theme Videhyan to be successfully realized, it needs just the qualities Adoor is best able to supply. Because, it conceives nature as informed by a vital spirit, it needs an imaginative apprehension of a nippy milieu. In fact, since it involves an acute dramatic conflict, it needs the power to express violent emotions with a spiritual significance that could not be conveyed through literal realism. It needs the power of poetic invention. This may sound like a red-herring, but the argument is essentially valid.

Adoor’s myriad thoughts on cinema come to light and he uses them bit by bit. However, he has a different take regarding film structure in India. Oftentimes, he has retorted that this is a definite problem with our film structure in India. As far as Nizhalkuthu is concerned, he thought then that it would definitely be realized in his own way. In fact, by now it should have been released, but since September 2002, when the film was previewed at Venus, it had been going from one festival to another: Toronto, London, Rotterdam, Rome, Busan and several other film festivals. Normally, he does not attend film festivals, but he produced this film, so he had to attend. On the question of commercial release, Adoor is in two minds. Basically, he is known as an antagonist to mainstream cinema, churned out by the Bollywood industry with boorish trappings and shown in mainstream theatres. The good thing is that in most big cities, you now have multiplexes, so it is, therefore, possible to release films like his in theatres with smaller capacities, making for a more economical business proposition.

Adoor’s mentor, Mrinal Sen, has always believed in low-budget cinema with the widest percolation to sundry public. Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s gamut of films is a pointer to these tenets, and rightly so.

Adoor is a filmmaker’s filmmaker, having so far executed and crafted twelve good, and possibly the country’s best films, untainted and botched by the usual hush-hush deals that abound in the Indian film world. He made a sound beginning with his directorial debut, Swayamvaram (1972). The title means the importance of making choices. Adoor made his choice, opting for serious cinema in a nation that worships blockbusters and clumsy storytelling, often told unrealistically on the screens. What he finds challenging in Swayamvaram is that the ideological as well as social dilemmas faced by the protagonist. These were to assume more complex forms in Adoor’s later films. But right from his debut, he has shown that ethics is as important to him as a film-maker, as are aesthetics and artistry. It has to be said, however, that he has never hammered them in without any driving motivation.

It is amazing to discover Adoor in scintillating moods though the prism of his films. It has its reason, premises of reasoning and logistics. He believes that creativity defies definition and explanations. “It is common knowledge that a person without the faculty of memory is incapable of imagination and creativity, he says. “Memory is linked to experience. It is stored in images or ideas by combining previous experience. Imagination is often regarded as the more seriously and deeply creative faculty, which perceives the basic resemblances between things, as distinguished from fancy, the lighter and more decorative faculty, which just takes in superficial resemblances.”

Apart from it, he was lucky to have a reliable lensman in Mangada Rama Varma. His works made a fascinating contrast to G. Aravindan’s epic style.

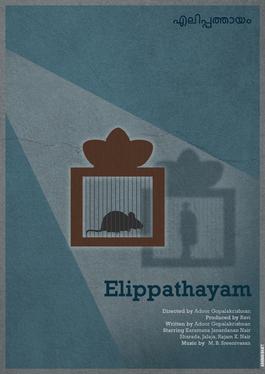

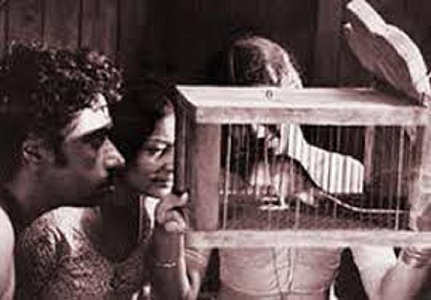

The music in Adoor’s films has resonated strongly with the audience. Elippathayam (1981) and Mathilukal (1989) saw Adoor playing characteristically different music. And this was not only innovative but also challenging.. It looks that both the films have ellipses while narrating digesis in film space. In actuality, music takes on the supportive role to enrich the content of the films.

Mathilukal is his most heart-warming film, where viewers forget the star (Mammootty) and see the character: Kerala’s much-loved and lionized writer, Vaikom Mohammed Basheer. Elippathayam framed a feudal lord gone to seed, drawing a parallel with the image of a rodent trapped in decadence. Undauntingly sophisticated and post-modern in form, the film went on to win accolades for the director’s command of the medium. Adoor found himself among an internationally brilliant pantheon of auteurs. National and regional awards poured in with every film, as did honours abroad, and retrospectives in numerous international film festivals.

Although Adoor is yet to make a film with a woman protagonist, women are not unimportant in his stories. In Vidheyan (1993), he places the emigrant settler Thommi, and his arrogant overlord Pattelar, between their wives. Sarojakka becomes Pattelar’s conscience that must be stilled, while Omana becomes dearer to Thommi because she has slept with Pattelar. As Vidheyan shows in the end, the ruler and the ruled adopt the same survival strategy. The difference between the master and servant is gone, giving way to the emergence of a new regime—freedom! The film is so cathartic and sexually frenzied, that at the end we feel like spitting on the arrogant and subversive Pattelar! Responsibility is an important theme in Adoor’s work. Believe it or not, the search for freedom and fraternity is another, though the journey does not end in utopia. This dream makes life worth living, its absence is stagnation. That is what Kathapurushan (1995) seems to say, as orphaned Kunjunni tries to find solutions in political ideologies since he feels disillusioned. In Nizhalkuthu (2003), Adoor weaves fantasy and fairy tale into a spatio-temporal reality in which the hangman’s tale intersects with the hanged man’s tale with shattering awe.

It may be mentioned, Adoor refuses to repeat himself or pin his works on tautological social subjects. In this aspect he stands tall and alone! Being an unhurried filmmaker, he launches projects only when he is mentally ready. To understand another facet of this seasoned filmmaker, though he began to make documentaries as a means of survival in the lean years, his records of Kathakali and Koodiyattam are masterworks of their kind. They show his familiarity with the aesthetics, finer moods and techniques of the classical genres and their gurus/mentors. In this regard, apart from his massive artistic films, he also made sundry documentaries. These reflect Adoor’s recurring themes of roots and soul that form his milieu. Across his works, we also see his characteristic humility and sense of wonder, a valuable springboard for his undying creativity.

Swayamvaram is said to be a beginner’s film, an experiment, and it was made close to fifty years ago. In these intervening years, spanning almost five decades, he has lived a lot, learnt a lot, and all of this reflects in the way he makes films even today. If you do the same things in the same ways, then what is the point? But when Adoor makes films, he keeps looking for new things to say and new ways to say them. To be precise, he does not want to get bored with the films he makes and the way he makes them. He probably thinks that if making the film doesn’t excite him enough, then why would the audience be excited to see it ?

His later film, Nizhalkuthu, pointedly focuses on responsibility—both of the state and of the individual. That part comes across very clearly in his later works too. Many say what is not clear, though, in Nizhalkuthu, is the bit about the son. Adoor shows him as a Gandhian, a participant in the freedom struggle who, among other things, is opposed to his father’s trade and to the practice of capital punishment. Despite this, he accompanies his father to the jail for the hanging that is the climax of the film. That is exactly the point and what matters in finality! He is shown fighting for freedom as he is part of the whole Gandhian movement. But what exactly is freedom? Freedom from whom, and to do what? Here Adoor suggests this: Examine the son’s story: His father is a hangman and gets land and other largesse from the state. The son is against all this; yet, he is dependent on his father’s lands and his income. In the end, he has the choice to either assume his father’s role or to starve. Man’s survival or surrender comes from crisis—this is the message that comes across, loud and clear, in Nizhalkuthu.

The question then arises whether that is only a choice or whether freedom really means the power to chose—for instance, does the son have the luxury of this choice in Nizhalkuthu? According to Adoor, the larger issue is whether we have fought for and got our freedom, or independence. But is it real freedom? Are we really free? These are the questions the audience ends up asking itself at the end of the film.

When the concept of freedom is debated, I find Adoor does not believe in compromise. The Kerala Film Academy crisis is a case in point. When he took over the Academy, he wanted to do new things. They organized a festival, they tried to bring in some innovations. But the minister concerned, Karthikeyan, thought he knew better than Adoor, and kept overruling him. Due to a clash of principles, Adoor quit the Academy.

To get back to Nizhalkuthu, this film seems a lot more stylized than his earlier works; with names like Ilayaraja for music, with much care given to cinematography, with tighter editing and crisper pacing than some of his earlier works. According to some critics, however, at the same time, the raw energy of his early films, like Swayamvaram and Kodiyettam, seem to be missing.

When Nizhalkuthu was not considered for the State awards, Adoor stood firm as a strict martinet. So, he sent an official letter to the State Academy saying he did not want his film to be considered for story, direction or best film, since, as producer and director, those awards would come to him personally. Adoor felt the minister was putting his own spin on his quitting and, therefore, he tried to make it seem as if he (Adoor) was interested in an award for Nizhalkuthu. But as Adoor said in the Rediff interview: “I don’t need to be, I have won every award there is in India, but that was the impression he gave.”

Simultaneously, it must be said that a lot of people put a lot of hard work into that film, he did not want to deprive all of them of a chance — so the film participated in all categories that did not have to do directly with him. And the funny thing is that it won all those awards — sound, music, editing, costume, acting… it won everything. What a loss of face for the Minister!

Another facet of Adoor is the way he writes a separate script for sound. And he literally walks miles to infuse life into this. Usually, it is claimed, he returns to the scenes of his film’s actions to capture the ambient sounds there. He would wait endlessly on tracks to record the hooting and hissing of the steam engine; would get drenched to have aquatic experience on the seashore, striving to record the roars of waves; would gleefully snuff out the stench of liquor from drunken guys to listen to their babble. Not only that, he would hide behind the walls of tutorial colleges to grasp the feel of young banter!

A scene from Elipatthayam, which won the British Film Institute Award for the most original and imaginative film in 1982.

Let’s take the film Kodiyettam. Here, all the sounds, except the dialogues, were recorded by him. He is said to have traversed across Central Travancore for nearly three months to capture every bit of sound from the source. Ramachandran, his sound engineer, merely handled the dialogues inside the studio. In fact, Adoor did much of the work from holding the microphone to record actual sounds! There are some great moments in this work:one of them is the film song you hear fading in and out from wayside stalls as the truck with Sankarankutty and driver speeds up. All lovers of Adoor’s brand of cinema must note the film-maker’s keen ear for film music is apparent in this one scene. In this context, I want also to take up the film Mukhomukham which taps up conversations in teashops, punctuated with old Tamil film songs. The use of the same only fortifies the power of the film in quaint way.

Finally, Adoor strongly believes in the importance of sound and silence at the same time. He is said to have realized the rare art of blending that has the right components in the right proportions. One such element is silence, which is surely the property of sound. We need to agree with the maestro that silence exists with sound and between sounds. Like he says, silence accentuates sounds.

The filmmakers nearly could not survive after one or two films. But Adoor would say the movement did not snowball, as they would have liked it to.

His vast role in the formation of FFC/NFDC, his objective view on the movement of cinema and individual films is a matter of serious concern. There was a time in the 1960s and 1970s when people like Adoor, the late Aravindan, Bakker, John Abraham and many other noted film-makers, pioneered a path towards quality cinema. In recent times, the number of such film-makers appears to have faded out.

Fortunately, though, the overall movement towards good cinema is still alive and well. But it is said Adoor had a problem with how his brand of cinema was labelled. “They called our films ‘art’, which was not bad in itself,” he says. The trouble was, he explains, that they labelled everything that was not mainstream as “art”, in the process, his and his contemporaries’ works got clubbed with a lot of “frankly unwatchable” films. All this created a situation where people rejected everything with the ‘art’ label. This led to further challenges for film-makers who shunned the mainstream approach to making movies.

Adoor believes the new age film movement is alive; but if you ask him to name individuals, he will say you should never judge such film-makers individually on the strength of just one film or two. It takes a lifetime to create a body of work.

Apart from this, many factors contributed to the process adopted; For one, movie-making has become a gamble, not a process of creation. Producers and directors have begun to think big is better:big star-casts, enormous budgets, etc. But the bottom line is, it is not how much you spend or how big something is, the audience is only worried about how good it is!

Despite being an eminent film-maker, renowned for his aesthetic films, Adoor has for long had reservation about television. According to him, television has a definite impact, not because television programming is good, but because it is so easy to access. Television borrows from films and competes with films. The audience for films has, therefore, diminished. “When you take that in tandem with the fact that films are becoming costlier, it means you are spending a lot of money on producing something, but less and less people are buying tickets to see it,” he said in an interview with Rediff in 2003 “Among other things, television has caused the decline of the middle-class movie-going audience; cable keeps them at home. To a film- maker, the middle class is the biggest audience and it is diminishing today. At another level, when the middle class was your biggest audience, films were made for them, they catered to middle class sensibilities. Today, the audience has changed; the films being made for them reflect that erosion in quality.”