The National Museum, Delhi, curated a temporary exhibition titled “Rama-Abhirama: The beauty of Rama in Indian Art and Tradition,” which was opened to the public on 18 December, 2017 in the presence of Professor B B Lal, the eminent archaeologist of Ayodhya fame. Stringing together a diverse range of material objects and art works from various cultures, and, yet, drawing from one “standard” narrative of the Valmiki Ramayana, the focus was on the divine hero of the epic. The first introductory plaque, which read more like an early medieval panegyric, states that the exhibition explores the beauty of Rama, emphasising on the aesthetics of rasa and bhava as experienced in the different episodes of the text, within a Natyashastric framework. Simultaneously, Rama’s “colossal personality” with “a combination of a perfect body and mind” is stressed upon. His “virtues” are said to have inspired artists. This interweaving of the ethical and the aesthetic, with an invocation to something that is ideal, desired and yet larger-than life and divine, says much about the contemporary curatorial imagination, in vogue in the National Museum. The second section focuses on “Tradition,” “which has been curated to emphasize on the performance and ritual aspect of Ramayana.” True to the prescribed process of rasa-anubhuti, or the experience of the rasa, the artefacts “invite the onlooker to be one with the expressions, emotions and beauty that (they) represent.” In a narrative which boasts of an ever-increasing number of characters, owing to its fluidity and orality prior to its canonisation, the onlooker has a range of characters to empathise with (sahridayi). Thus, the apparently mute sculpted, moulded, painted, embroidered, and etched narratives mellow the domineering glory attributed to the epic’s hero in the introductory statement, bringing to life the multifarious and flowing character of the many Ramayanas, as opposed to a monolithic, classical text.

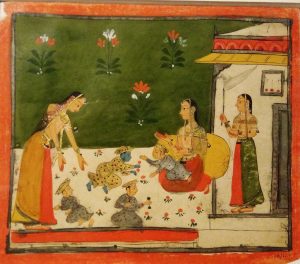

The exhibition spans the varied natural geography of the subcontinent, evident from the provenance of the objects on display. The materials are as diverse as wood from the Tamil country, leather from Kerala, terracotta and stone from Bengal and Central India respectively. Diversity is also seen in terms of the different sites of production—the court, the temple, the marketplace, and the village home. The characters of the epic mould themselves to suit their immediate environment. For instance, a wooden panel from 19th century Kerala shows Rama in warrior positions, perhaps drawing references from Koodiyattam, and a few faces show striking resemblance with the headgears used in temple theatrics. The exhibition is planned episodically, in seven parts, or kandas. The first segment, or the Bala Kanda (the first book in Valmiki’s Ramayana, the Book of Youth), is reconstructed through paintings, largely medieval and early modern, depicting Rama as Dasharatha’s son, growing up with his brothers, the princes of Koshala. Paintings like “Bala-Rama with Kausalya” from 16th century Bikaner, and “Rama enjoying food with his brothers” from late 18th century Kotah, do not hint at the divinity of the epic hero, but emphasise on the court society he was nurtured in. As Romila Thapar notes, the Ramayana can be seen as a “charter of validation for kingdoms established in areas of erstwhile chiefships.” The Aranya Kanda (the third book in Valmiki’s Ramayana, the Book of Forests), on the other hand, accommodates alternative political formations like chiefships, as seen in the organisation and institutions of the vanaras and the rakshasas. The rakshasa is the “alien/other” encountered in the forest, embodying everything opposite to the norms of the kingdom—they are tied by kinship links reminiscent of the clan society, are referred to as ganas when in groups, don’t have genealogies (there are exceptions), and are usually associated with magic rituals. “The elements highlighted are their violence, their magical power to metamorphose like the gods, and their intemperate sexuality.” Thus, the rakshasa is indispensable to the narrative, should the author desire to highlight the virtues of the hero at the helm of the kingship society. Interestingly, the motif of exile and its location, the forest, makes apparent the distinction between the ideal kingdom championed by the epic and the erstwhile, primitive social formations, and starts the process of divinisation of the hero. “The king’s analogy with a god stems from his function to protect.” (Thapar: 2013).

However, in some other Rama stories, the portrayal of rakshasas is very different from that of Valmiki’s or Kamban’s. Vimalasuri’s Paumcariyam in Prakrit, as a counter-epic or a prati-purana in the Jaina literary tradition, is sympathetic to the rakshasas and glorifies the Vidyadhara lineage. A.K. Ramanujan remarked that if one thought of the Rama narratives as “a series of translations clustering around one or another in a family of texts,” Vimalasuri’s Paumcariyam and Valmiki’s Ramayana could be seen as symbolic translations of one another, in Peircean terms (Ramanujan:2004). In symbolic translations, the later text uses the plot, characters, and names of the earlier text minimally and to say new things, “often in an effort to subvert the predecessor by producing a counter-text.” The exhibition was lacking in diversity in terms of symbolic translations. But the sheer range of localised narratives, as embodied in the objects, was impressive. A statuette of Hanuman carrying an offering from Bastar is very different from the courtly depictions of the monkey god. Cast in bell metal or dhokra, using the lost-wax process (cire-perdue), it is rustic and uneven, rooted in its ethno-geographical context. A provincial Mughal painting from 17th century Orchha, Bundelkhand, titled “Rama breaking the bow of Lord Shiva in the court of Raja Janaka at Mithila,” places Rama in a resplendent Mughal court, with Persian rugs, frescoes, niches and awnings characteristic of Timurid and Mughal settings. One is reminded of the Freer Ramayana (1597-1605CE) commissioned by Abd al-Rahim Khan-i-Khanan, which has Akbar’s imperial city, Fatehpur Sikri, as the setting for the epic. Rama is seen holding court in red-sandstone buildings and chahar-baghs. According to Ramanujan, these texts are indexical—they are embedded in their local context, like Krittivasa’s Ramayana, in which Rama’s wedding is a Bengali wedding, with Bengali customs and cuisine. The Yuddha Kanda (the sixth book in Valmiki’s Ramayana, the Book of War) displays an exciting array of temple terracottas from Bengal, showing warring contingents in continuous panels. Interestingly, on temple walls, the epic motifs jostled for space with scenes from everyday life in early modern Bengal—Portuguese ships, hunting scenes, soirees at the landlord’s court. In the museum, a war panel is merely a fragment of the grand collage and, thus, a part of the total visual experience.

Performance and folk exhibits like Chau dance masks, wooden masks from Koratpur, leather puppets from Andhra, Raghurajpur paintings, Patachitra scrolls from Midnapore and Murshidabad, and a lost-wax artefact from Bastar are all different tellings of the Ramakatha. The shadow puppets are exhibited in a performative setting, against a traditional shadow screen. The well-researched curatorial note introduces the onlooker to the various traditions of shadow puppetry—Tolpava Koothu in Kerala, Bomalattam and Tholu Gombeytta in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, Ravanachhaya in Odisha, and Charma Bahuli Natya in Maharashtra. It further discusses the technique and socio-dynamics of puppetry in these regions. The most sprawling exhibit on display is an embroidered temple hanging from South India (possibly from one of the post-1565 Nayaka territories, or successor states of the Vijayanagara kingdom). In an elaborate sequence of characters, it depicts the court of Rama. The exhibition, though planned along the lines of Valmiki’s telling, facilitates a dialogue between the many tellings. The utility of certain objects brings out the everydayness in Ramakathas, alluding to the impermanence and fluidity of the divine, or perhaps a South-Asian magic realism of sorts. One is again reminded of Ramanujan’s brilliant essay, “Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation,” which captures the essence of the tellings with unmatched clarity.

These various texts not only relate to prior texts directly, to borrow or refute, but they relate to each other through this common code or common pool. Every author, if one may hazard a metaphor, dips into it and brings out a unique crystallisation, a new text with a unique texture and a fresh context. The great texts rework the small ones, for ‘lions are made of sheep,’ as Valery said. And sheep are made of lions, too: a folk legend says that Hanuman wrote the original Ramayana on a mountaintop, after the great war, and scattered the manuscript; it was many times larger than what we have now. Valmiki is said to have captured only a fragment of it. In this sense, no text is original, yet no telling is a mere retelling—and the story has no closure, although it may be enclosed in a text. In India and in Southeast Asia, no one ever reads the Ramayana or the Mahabharata for the first time. The stories are there, “always already.”