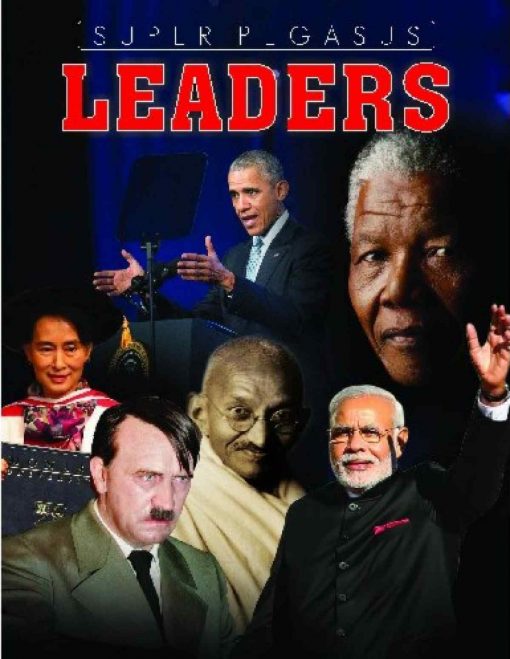

The New York Times and The Guardian have recently published articles about a children’s book imprint Pegasus that lists Adolf Hitler as one of the great leaders of the world in one of their books. While Kai Schultz’s article in The New York Times reported that Adolf Hitler is seen as an important leader in India, the connection between Hitler’s rising popularity and India’s own brand of fascism, Hindutva, went relatively untouched.

The book has been withdrawn by the publisher after the Simon Wiesenthal Center, an international Jewish human rights organisation, raised concerns over the book. Several Indian news broadcasters, like The Wire, The Quint, and the Deccan Chronicle, have also reported on the issue.

Leadership is an important skill in India – it can make Prime Ministers and absolve politicians, even those who are known to justify violence on some kind of pretext.

The reasons why Indians consider Hitler and Modi as leaders are the same. They can look away from Hitler’s hatred for the Jews; they can also look away from Modi’s hatred for Muslims. Modi had not shown any remorse after the 2002 Gujarat riots, which many commentators, including a former police officer Sanjiv Bhat, in a sworn statement to the Supreme Court of India, has called a state sponsored riot.

A 2003 report in Outlook by Zahir Jan Mohamed, also mentioned by Schultz in the course of his essay, says that a 2002 poll organised by The Times of India found that Hitler was placed third, after Mahatma Gandhi and the then Prime Minster of India Atal Bihari Vajpayee, in an online poll on “ideal leaders India needs most” which was conducted among students in “India’s most prestigious colleges”. Apart from merely reporting the results of the poll, the article also explored the possible causes for it:

When we look at government issued textbooks in India, these results should not surprise us. In a Standard 9 textbook for the western state of Gujarat, Hitler is cited as a man who gave “race pride” to his people. There is no mention of his ghastly treatment of Jews. In the chapter, “Problems of the Country,” the first subsection is entitled “Minorities” in which Muslims, Jews, and Christians are called “foreigners in India.”

Mohamed was probably referring to textbooks written in Gujarati, which are read by a far larger section of students in Gujarat than textbooks in English.

Although this alone cannot be cited as the reason behind the 2002 Gujarat riots, it provides important clues as to why Modi emerged victorious in the state elections after the riots, and his meteoric rise since then. It finally led to BJP’s resounding victory in the 2014 national elections with Modi as a Prime Minsiterial candidate.

This peculiar obsession with leadership continues in his stint as the Prime Minister of the country. This was evident in the support that Modi received among the people after the infamous demonetisation plan. Lives were lost; the Reserve Bank of India said that it did not recover black money; and India’s GDP growth went downhill. Newspapers rued why, in spite of such clear markers of its failure, the people still had faith in the operation. They may not have had any faith in demonetisation, but they certainly believed Modi when he said that the plan would help recover black money in India.

One way to understand the correlation between the rise in Modi’s popularity and India’s fascination with Hitler, is to track the admiration that Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) founders felt for Hitler.

Modi has been a member of the Sangh and is a strong advocate of its advice on matters related to policy, unlike Vajpayee who had tried to distance the work of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) from the Sangh.

Modi has also allowed for certain appropriations to occur which might, in the first glance, seem like contradictions. If the Sangh was anti-Semitic and considered the Jews (along with Muslims and Christians) foreigners, how can one explain Modi’s close ties with Benjamin Netanyahu and the exponential growth in business between Israel and India?

Once again, it may not be a contradiction if we see it culturally.

One can find similarities between Netanyahu and Modi as “great” leaders. The similarities are also ideological. Israel’s state policy is influenced by Zionism that treats native Palestinians as outsiders. Similarly, the RSS treats other religions, apart from Hinduism, as outsiders in the Indian subcontinent. Interestingly, both these attitudes mirror Hitler’s attitude towards the Jews.

But does this mean that Modi’s popularity is unchallenged?

Who are the dissidents in Modi’s India? Primarily, the students and intellectuals.

This is not a coincidence. For instance, the intellectual class has systematically objected to incorrect and dangerous changes in school text books, like the ones in Gujarat. They will require something more than trust to buy what Modi is selling. They can see through the failures of demonetisation. They ask: Modi might be a leader, but what kind of a leader is he?