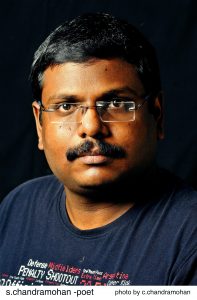

I assert my identity as a “dalit poet writing in English”. I see myself as very privileged because I have the opportunity to be in conversation with a very large readership through my poetry. A poem or a work of art can be used to register our dissent against oppressive regimes, like the current right-wing government in power. This is what I have tried to do through my poetry. In fact, my second collection of poems was chosen as the runner up for a prize precisely for its “incisive” and “subversive” themes.

If literary accomplishments reflect merit, then I must be a promising poet. I came close to winning the Srinivas Rayaprol Prize in -2016 But, I suppose, for those keeping score, my words may carry more weight now that I have been selected for International Writing Program, offered by the Iowa University, for the year 2018.

Perhaps there is another reason why my work has been scrutinised, put under the scanner, more often than that of my contemporaries. As one of the very few dalit poets writing in English, my poems strive to use an alternative sense of aesthetics; alternative, in terms of cultural justice and linguistics (for instance, the idiom that I use).

In this article, I attempt to carve out my notion of “imagined justice”. At the outset, I would like to anchor this notion squarely on the individual rather than anything else. It is interesting how often I am asked what my idea of justice is. Perhaps, this is done to see how my ideas measure up against the idea of justice put forth in Namdeo Dhasal’s “Man, you should explode!”

1. Reclaiming One’s Own Agency

The political situation in the country today is becoming increasingly hostile. With the government washing its hands off every welfare scheme, the onus of articulating a sense of justice falls on the individual. Perhaps this is the essence of identity politics. We must first create our own ideals before they can be implemented in this tangible and real world. Every dalit- bahujan first dreams for herself or himself, and then sets out to achieve it. Maybe I should acknowledge that it is a privilege that I am writing in the English language and have a laptop on which I can type and assert my Ambedkarite self. The dalit-bahujan generation before me had other things to worry about: their struggles were focussed on fighting for the civil rights of Dalits. So it is my duty to first prioritise this notion of social justice anchored on caste-annihilation rather than any other parameter.

2. Inviolable Dreams

I dream of a world where every individual’s dream is inviolable. There are no limits to the endeavours of the Dalit or the Queer or the Woman. This dream is an articulation of an alternative world which is devoid of glass-ceilings.

In order words, everyone’s fortunes are drawn from the same set of probabilities in the world. Is there any place in the world, at least in the Western hemisphere, where these glass-ceilings have been shattered? I doubt it. The sad part of my articulation of justice is that people of our own kind will have to do most of the work to shatter such glass-ceilings.

3. Towards an Inclusive Language

If being a poet calls for a deeper engagement with “language”, I would like articulate a part of my notion of justice in terms of this “language”. If I was to become a canonical poet, as well known across the world as Aime Cesaire, I would dream of a world built with word-bricks that excludes no one. If a nation or a society ever had a lingua franca, it shouldn’t, by-default, exclude a section of the society. Otherwise, it is like an elevator that has not “evolved” enough carry the differently-abled. In the current milieu, perhaps it is queer assertions that push the frontiers of linguistic expression. Similar movements de-stigmatise every word and their corresponding worlds. This is like saying that there are parts of this world (tangible or intangible) that I haven’t visited even in a dream! This constraint could be “linguistic” more than anything else. Finding such a language would be my holy grail.

4. Towards a Common Language of Protest

As a dalit poet writing in English, can I not dream, at least occasionally, of becoming a part of our fight for justice? Is protest a celebration of difference? Is it feasible for all the protests in this global village to have a lingua franca? Can we pen a universal marching song? Or, is my writing in English merely an extension of the ongoing social renaissance: wasn’t it the British who laid the foundation for the rise of someone like Dr Ambedkar and many other social reformers of this country? If the current fascist regime wanted to suppress the multitudinous struggles that are being spearheaded by the people, isn’t it in our interest that the various protesting groups have a common language of discourse? Or is it in our interest to develop tongues that are sensitive to the “taste buds” of “the other”? Carefully crafted poetry may serve these ends.

Listen to Chandramohan S read his poems here.

Also read an article by the poet on the People’s Lit Fest in Kolkata here.