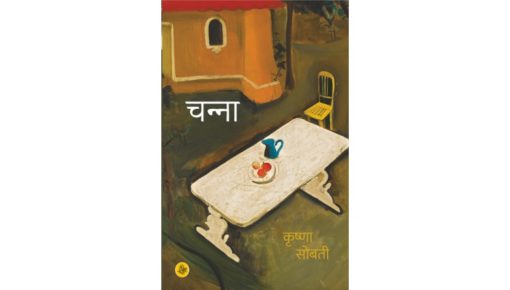

The last time I saw Krishna Sobti, a few days before she left us on January 25th, 2019, visitors to her hospital room passed around a book. It was a reissue of her first novel, Channa. The book – its history – brought together for us the grand old woman and the grand old writer. Sobti had sent the manuscript of Channa, her first novel, to a publisher in 1952. But when she got proofs of the novel, she found changes in the text. The changes included the use of Sanskrit words to alter her use of Punjabi and Urdu. Sobti withdrew the book; she paid to have printed copies destroyed. Decades later, she revisited the manuscript, and agreed to have it published. And now, in January 2019, here it lay by her hospital bed, as if to remind her of the long path she had travelled so well.

That is the sort of writer she was: uncompromising. That is the sort of woman she was too, uncompromising, outspoken; an original.

In 2015, when writers across the country returned their Sahitya Akademi awards in protest against growing intolerance in the country, Krishna-ji was there to support them. Old age was not going to stop her. She was there, in a wheelchair, at “Pratirodh”, a public meeting of writers and activists in Delhi. Onstage, she read what she had written. As always, what she had to say was sharp, clear-headed, important. She began with what she had seen and felt in her long life: British rule; the freedom struggle; the memory of revolutionaries walking with their heads held high, still alive in her heart. But it was the distortion of this memory, the division of Indian citizens by a hatred-driven ideology, that she was there to condemn. First Babri, she said, then Dadri, in the name of Hindutva. Hindutva’s “bravery” she described as impotent. She criticised those trying to replace history with mythology; those who promote superstition. This is a time fraught with danger, she said, a time when writers and intellectuals have to join the larger struggle of citizens. But she, wise woman that she was, also offered hope. This nation, she said, has never compromised with its values, and this time too, she was confident that the people will not lose sight of the right thing to do. This was the intelligent faith she chose.

I had read some of her work in English translation, and met her a few times at literary events. But it was in her last years, when she agreed to be an advisor to the Indian Writers Forum, that I got to know her. It was a wonderful gift, this unexpected friendship. Our conversations ranged from writing to politics to language to women’s lives. There was much laughter – there was nothing of the sweet old woman about her. At the hospital that last day, her eyes were shut, though she seemed to hear me when I spoke to her. She smiled at what I said. But I don’t want to think of that as a goodbye. I would rather recall the evening at her flat when she suddenly took my hand in hers and said, with passion and wonder in equal measure: “You know, life is a wonderful thing. Live it!” Krishna Sobti, those you inspired, those you befriended, will not let go of life. We will speak up and write – as fearlessly as you did.

Read more:

“आज़ादी हमारा पैदाइशी हक़ है”: कृष्णा सोबती

Dil-o-Danish: A Reading from Krishna Sobti’s celebrated novel