Mirai Chatterjee, Rolee Srinath, Saba Sharma, Radhika, Shaminaj Khan

A series of interviews, begun on International Working Women's Day, with women teachers, journalists, musicians, students, lawyers, startup employees – all young, established, or retired professionals in their fields – discussing gendered aspects of their work and working life. Stay tuned for more!

'Three hares looking at the moon', ca. 14th – 17th c. / Taimur Khan

'Three hares looking at the moon', ca. 14th – 17th c. / Taimur Khan

Mirai Chatterjee

Ahmedabad | Public health professional

The Self-Employed Women’s Association, SEWA, where I have been working for over three decades, is a national union of almost 20 lakh women workers in the informal economy. Such workers represent over 93% of the Indian workforce. Since we organise women into their own unions and cooperatives, women are at the centre of all our efforts. In membership-based organisations (MBOs) and movements like ours, it is their needs and demands that provide direction for all action. We believe, as Gandhiji did, that the struggle for women’s equality, and for a just and equitable society, is best led by women, especially the poorest and most vulnerable – informal women workers.

These core beliefs and values have influenced our public health work at SEWA as well. First, we have taken an ‘organising approach’ – that first and foremost, women must be organised into their own MBOs, such as unions, cooperatives and self-help groups (SHGs), where they themselves are the users, managers and owners. This unity and solidarity – the sisterhood – is the first and quintessential building block for improving the health of women, their families and communities. All else follows. Second, improving our own health and that of our communities must be undertaken by women themselves. So it is the women, SEWA members, who learn to be health workers in their own villages and neighbourhoods. And they have shown that they can do this with great commitment, energy and enthusiasm! Third, with women managing their own MBOs, health action reaches everyone in the community, in a manner that is sustainable in the long run. Our SEWA sisters, being poor and vulnerable themselves, are inclusive and serve all, especially those usually left out. They ensure that not only their own families, but all benefit from local health action and services. Fourth, they show an admirable patience and persistence. Over time, they become strong and fearless leaders, challenging all injustices and exploitation, including patriarchy.

I feel so inspired by these women of our country, even after 30 years! I have witnessed so many women bloom and grow into strong public health workers and leaders, transforming their families and communities.

One thing that keeps recurring in my experience of public health action at the grassroots level is the tremendous sacrifices that women and girls make. First of all, women and girls seek healthcare least and last, conserving their families’ hard-earned resources. However, they are willing to go to any lengths to preserve and protect the health of their husbands and children. In SEWA Bank, the number one reason women take loans is sickness – their own or that of their families. I remember one woman who, after the earthquake in Gujarat, managed with a broken leg for three weeks, saying there would be no one to take care of her family, cook and clean, if she went to hospital.

A surprise for me which has challenged my own ideas is how young men, rural and urban, are ready to engage with gender issues in a sensitive way. They asked us to provide them with gender-sensitive reproductive and sexual health information, and wondered why we had left them out.

Being a woman has been very useful in my area of work. Public health being a service-oriented or ‘care profession’, people expect more women to be involved and, I find, are more open to our suggestions, as well as in interactions concerning health and the body. Also, women and girls are more comfortable sharing their health and related issues with a woman. So it has been a net advantage to be a woman in public health.

I feel that public health is not only one of the greatest needs of our country, but also offers much scope for action and service by young people. We need thousands of public health professionals and para-professionals across the length and breadth of India. It is a growing profession and a further boost is expected with the National Health Policy having received cabinet approval earlier this year, and the proposed public health cadre. My advice to young colleagues would be to seriously explore this area of work – it is very challenging and also deeply satisfying. The most important aspect of public health is to work in the field, i.e. where the people who most need us live and work. By being out there, one learns so much, is equipped to face the challenges and to deal with them through feasible solutions developed with local people, especially those who need these most – the vulnerable, like Adivasis and Dalits, and the women and children of our country.

Rolee Srinath

Teacher, school principal | Delhi

I am an educator and our job is to nurture young people and not only help them gain knowledge, but also guide them in meeting life's challenges. We aim to provide them with opportunities to develop their personalities so they may become responsible and accountable adults. As a woman, I feel, we are more sensitive to students' needs and are better able to instil values and discipline in them. Women teachers are more organised when it comes to curriculums and evaluation. As a biology teacher, it was challenging to teach topics concerning sex to both boys and girls that were more often than not overlooked by our male colleagues. Women principals also, I have found to be more numerous and very successful. Women are also well represented at the higher levels of the department of education (district heads) in the Delhi administration.

In the teaching profession the number of men and women is roughly equal. Traditionally, more women opt for this path at the onset of their careers. It has given me great satisfaction as it is most suited to my temperament and has been highly rewarding. Whether in teaching or as an administrator it gives me no greater joy than to be remembered, to leave a mark in the hearts of students and to celebrate in their achievements.

Young men and women entering the teaching profession need to be more motivated and responsible as they are truly sculpting the future generation, and should not take see it merely as a means of livelihood. Unless highly principled and possessing sound convictions, they will be unable to influence young minds and bring about a change for the better. The greater rewards lie in realising the potential of students and helping them translate it into accomplishments which transcend monetary compensation.

Saba Sharma

PhD student, Politics | Delhi, Cambridge

I'm doing fieldwork for my PhD at the moment, on governance in the Bodoland area of Assam, with a focus on various village-level institutions. One of the things I'm looking at is a community police system specific to Assam (although some other states have their own variants of community policing, like Kerala), and it's particularly interesting to see how women fit into this structure. At the level of state policy, there is a big push to recruit more women in the community police, but as this goes through various levels of implementation, you see a lot of confusion and resentment on the part of men, including officials, about getting this done. There are a lot of questions about whether women can police, whether they will be able to be as independent and mobile as men, whether they can be providers of security when they are perceived as needing protection themselves. But in areas where these women representatives already exist, you see that they can be quite proactive, especially when it comes to things like reporting domestic violence or sexual violence. It's an interesting example, I think, of how policy is conceived and interpreted at different levels. In this case, it also shows that progressive initiatives, even when codified in law or made 'official', face resistance from existing gender norms.

During fieldwork, particularly, I expected it to matter that I'm a woman, and I think it does. It does matter in terms of how you yourself think about things like safety, and also how seriously you are taken (occasionally you can also use this to your advantage). I think this would be true for most women doing fieldwork, and you see a lot of reflections about it in anthropology, sociology, geography, etc. – how it impacts the way you are perceived and so on. In my case, I think it also intersects with other aspects of my identity – such as not being from Assam, studying in a foreign university, generally being an outsider. I think the 'outsiderness' also subverts some of the expectations people otherwise have of women – that it's strange to see them on their own, doing something independently. To be fair, I think Bodoland/ Assam might in any case be more open-minded about this than the parts of north India I'm familiar with. There is still violence and inequality, but some of the daily harassment you sometimes see in Delhi – people constantly staring or making comments – is missing.

Radhika

Community media, Video Volunteers | Goa

Whenever I meet these women, we inevitably talk of ‘freedom’. Such a touchy term it is. Most people are curious whether I’m married, and why not. I tell them of my inability to comprehend the idea of sharing my life and dreams with a person who would expect me to be nothing more than their slave. Not all men are like that, they say. I agree, somewhat sceptically. I also ask them why they never ask men if they’re married – my male colleagues are rarely questioned about their marital status. We discuss how our society brings up children in gender-specified and well-compartmentalised roles. We talk of how ‘mard ko dard nahin hota hai’, and laugh about how the good men are always taken. I wonder aloud if there are instances of same-sex relations in their villages, and some of the women giggle, others blush, and someone lightly slaps my hand, saying, 'Let’s talk about something else now…'

The author with members of the Janwadi Mahila Samiti in Sonepat. The JMS is a small, village-level group affiliated with AIDWA, Haryana.

The author with members of the Janwadi Mahila Samiti in Sonepat. The JMS is a small, village-level group affiliated with AIDWA, Haryana.

We go on to argue about who the biggest perpetrators of Patriarchy are. Sunita, an educated, ‘liberated’ young woman with a college education, is married to an army officer. Armed with a degree and nationalistic fervour, Sunita tells us that women are the ONLY reason why patriarchy continues to proliferate, and goes on to describe how the overpopulation of minority communities is the reason our country is in such a mess. As she speaks, I’m desperately looking for the correct Hindi words to respond in the ‘right’ way, but before my mind can come up with a response, the other women laugh her into silence. These Haryanvi women, compelled to live in ghoonghat and rarely allowed to step out of their homes, have possibly put their lives at risk to be here. And they’re not willing to accept more patriarchal shit dished out for free. With gentle disdain they describe to Sunita how she’s just another unfortunate victim of Patriarchy. Men are not taught to cook or clean, or to maintain homes. They’re taught that their sole purpose in life is to father children, get good jobs, have a house, a car, provide for their children… They’re brought up with parochial, patriarchal terms and conditions, ‘humare ghar ki auratein bahaar kaam nahin karti hain, kya zaroorat hai, itne saare mard hain paisa kamane ke liye…’ (Women of our household do not leave the house to earn, what is the need? There are enough men here…). That society compels men and women alike to fit into certain social roles and norms, and that this, in its entirety, is patriarchy. They go beyond my limited understanding of gender in a Haryanvi village, and tell Sunita that her pride in her husband’s gun-toting ways is Patriarchy. An older woman takes Sunita aside to further explain to her how peace is the only answer, and that war is a weapon created by corporates and politicians. The rest of us continue to talk about the limits and conditions within which we understand 'work'. I am amazed at the depth of understanding these women of the ‘dehaat’ have of life beyond their village. They tell me some of them have learnt how to read from their children, and regularly read aloud for others from the few newspapers that reach their village. I am convinced that they are far more empowered than the pouty, hair-straightened specimens which Instagram their way through life in the cities.

Shaminaj Khan

PhD student, Sanskrit | Delhi, Sagar, New York

शादी हमारे समाज की एक निरन्तर और अपरिवर्तनीय परंपरा रही है। लेकिन मुझे लगता है कि यह परंपरा हमारे समाज में लड़कियों के लिये एक बड़ी समस्या भी है। इक्कीसवी शताब्दी में भी लड़कियों को शादी के लिये मजबूर किया जाता है। जो लड़की अपने पैरों पर खड़ा होना चाहती है उससे ये कहते हुए कि 'लोग क्या कहेंगे, अपने माँ-बाप की ख़ातिर शादी कर लो' ऐसी जगह शादी करने के लिये मजबूर किया जाता है जहाँ वो शादी नहीं करना चाहती। सभी जानते हैं कि भारत गाँवों का देश है और इसकी 80 फीसदी जनता गाँवों में निवास करती है। जहाँ पितृसत्तात्मक समाज प्रचलित है। और गाँवों की बात छोड़िये शहरों में भी ये प्रचलन देखा जाता है। शादी के मामले में लड़की की मर्ज़ी पूछना यहाँ का रिवाज ही नही है। हम नारी सशक्तिकरण और उसके अधिकारों के बारे में किताबों में ख़ूब पढ़ते हैं जिनमें साफ़ शब्दों में लिखा होता है कि हर लड़की को अपनी मर्ज़ी से अपना जीवन साथी चुनने का अधिकार है। लड़की को कब और किससे शादी करनी है ये उसका जन्म सिद्ध अधिकार है। लेकिन जब मैं अपने आस-पास के माहौल को देखती हूँ तो ये महिला सशक्तिकरण की बातें धरी की धरी रह जाती हैं। और मैं सब समझते हुए भी लोगों को नहीं समझा पाती। मुझे बस एक ही जवाब मिलता है कि ‘बोझ जितनी जल्दी उतरे उतना ही अच्छा है’। मुझे ये समझ नहीं आता कि किस शब्दकोष में बेटी का समानार्थी बोझ है।

मैं एक छात्रा हूँ और सौभाग्य से मुझे भारत की एक बहुत ही अच्छी यूनिवर्सिटी में अध्ययन का अवसर मिला। जहाँ लिंग-भेद जैसी तुच्छ मानसिकता नहीं पनपती। अगर मैं किसी दूसरी यूनिवर्सिटी में होती तो मुझे ये समस्या झेलनी पड़ती। जैसे 6 बजे के बाद होस्टल से बाहर न जाना। पुस्तकालय में न जाना ताकि लड़के डिस्ट्रैक्ट न हों। लड़कों के साथ न घूमना आदि। जो मैंने अपनी दोस्तों से सुना है कि उनके साथ ऐसा होता है।

जो लोग शोध करेंगे उन्हें मेरी ये सलाह है कि ऐसे विषयों पर शोध करें जिनमें महिलाओं के अधिकारों को किसी धार्मिक ग्रंथ से जोड़कर दिखाया गया हो, क्योंकि लोग हमारी बातों पर यक़ीन नहीं करते, लेकिन जब हम उन्हें ये बताते हैं या सुनाते हैं कि हमारे धर्म के इस ग्रंथ में ऐसा है तो शायद वो लोग हमारी बात पर यक़ीन करें। और जो लोग लड़की या महिला के छोटे-छोटे हक्क़ के भी विरोधी हैं शायद पक्ष में हो जायें।

Marriage has been an eternal, unchanging tradition in our society. But I think this tradition is also a big problem for girls in our society. Even in the 21st century girls are compelled to get married. A girl who wants to stand on her own feet will be urged to 'Think what people will say, for your parents' sake get married', and be compelled to marry into a home she doesn’t want to. Everyone knows that India is a country of villages, and that 80% of its people live in villages. Where patriarchal society prevails. Forget villages, this custom is seen in cities too. When it comes to marriage, it is not the norm here to ask after the girl’s wishes. We read a lot about women’s empowerment and women's rights in books which clearly spell out that every girl has the right to choose her life partner. Deciding whom to marry and when is each girl’s birthright. But when I look around me all this talk of women’s empowerment comes to nothing. And though I understand all this, I am unable to make other people understand. I get just one response, that ‘The sooner the burden is lifted, the better.’ I am unable to understand which dictionary lists ‘burden’ as synonymous with ‘daughter’.

I am a student and fortunately I was given the opportunity to do research at a very good university in India. Where a petty mindset like gender discrimination doesn’t flourish. If I were at another university I would have to put up with this problem. Like not leaving the hostel after 6 p.m. Not entering the library so that the boys aren’t distracted. Not walking around with boys, and so on, all of which I have heard from my friends happens to them.

To those planning to do research, my advice is to study those subjects where the rights of women are elucidated with respect to some religious text, because people don’t believe what we say, but when we show or tell them that ‘this is stated in this particular book in our religion’, then perhaps those people will believe us. And those who are opposed to even the least rights for women or girls may perhaps come round to our view.

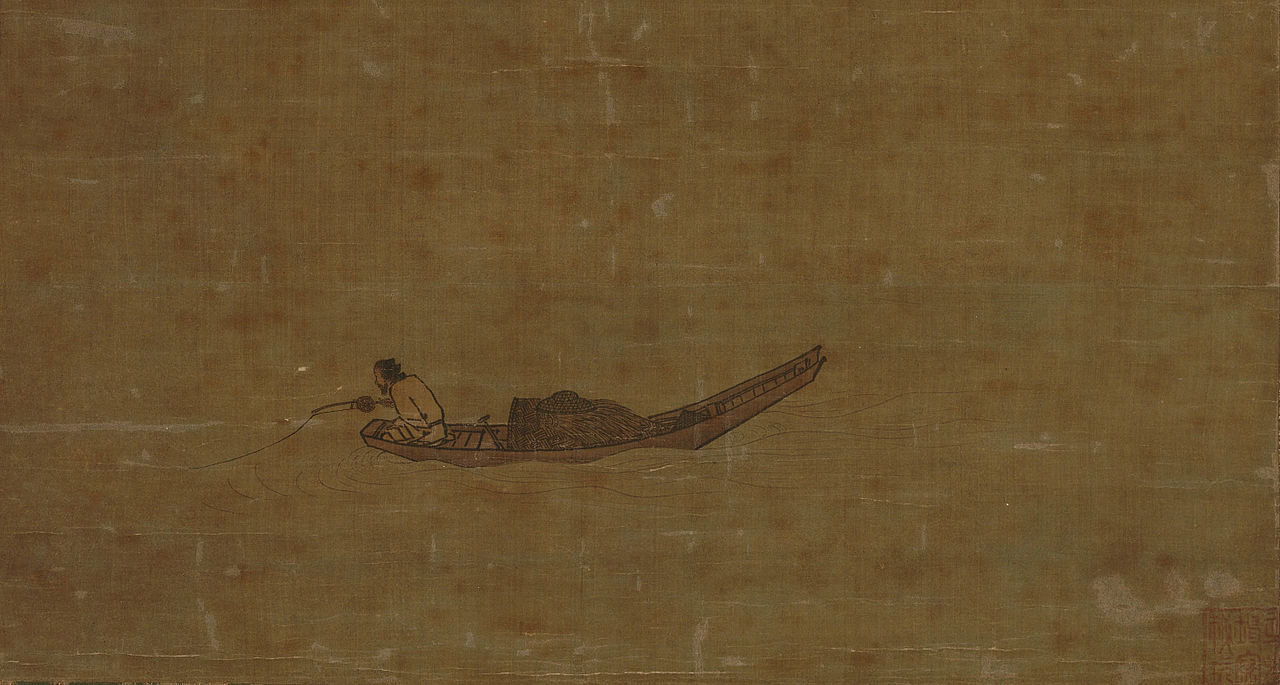

Ma Yuan, 'Angler on a wintry lake' / Wikimedia Commons

Ma Yuan, 'Angler on a wintry lake' / Wikimedia Commons

An ICF series of interviews begun on International Working Women's Day: