Telugu writer Volga’s book, The Liberation of Sita, was recently awarded the Laadli Media Award for Gender Sensitivity in Fiction for 2017. This is cause for celebration for more than one reason: in 2016, when the Telugu newspaper Andhra Jyothi published a story of hers called “Asokam”, she was threatened by the thought police for her re-telling of the story of Mandodari, Ravana’s wife.

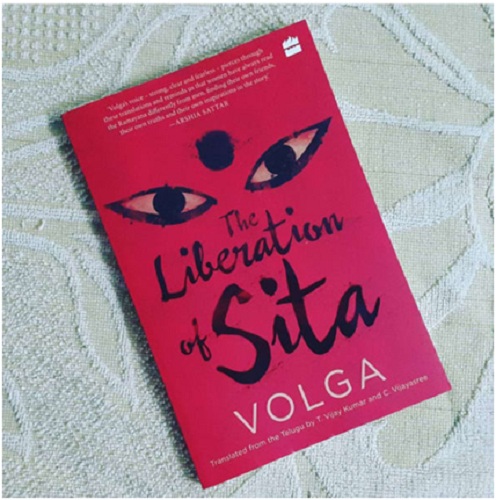

To celebrate the past and future liberation of many Sitas, and the work and activism of Volga, the Indian Cultural Forum has put together extracts from The Liberation of Sita translated by T. Vijay Kumar and C. Vijayasree; extracts from an interview in the same volume, as well a recent conversation with the Indian Cultural Forum, accompanied by a Hindi translation by Karthik Venkatesh of a story from the collection Political Stories (Rajakiya Kathalu).

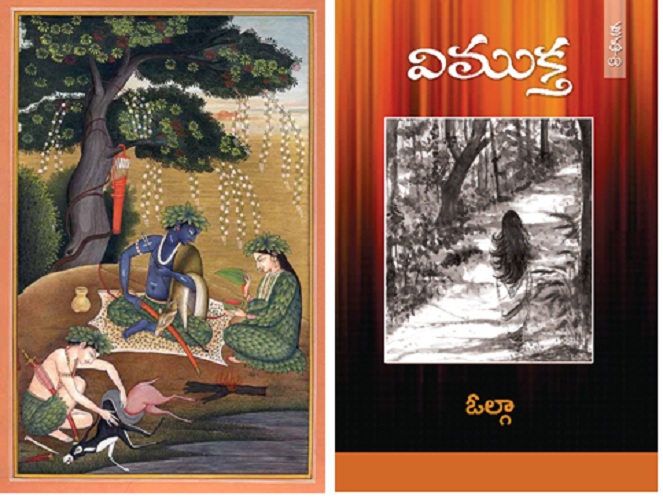

Left: Image Courtesy: Shakti Sadhana; right: Vimukta – the Telugu original of The Liberation of Sita

Left: Image Courtesy: Shakti Sadhana; right: Vimukta – the Telugu original of The Liberation of Sita

Popuri Lalitha Kumari, the award-winning Telugu writer, feminist and activist, uses Volga as her pen name. The name holds a story: Lalitha’s elder sister was born on the day a Soviet girl called Volga was killed by the Nazis. Lalitha’s father, a communist, named his daughter Volga in memory of the dead girl. When Lalitha’s sister died, she, Lalitha, took on a double memory to become Volga when she wrote.

This nugget of a story is something of a signpost for Volga’s work. Her stories are layered with collective pasts, and varying memories of the past. Equally plural are the ways to frame this raw material to understand what a life in the present is all about, and where it should move ahead to make more complete individuals, and more egalitarian societies. When Volga writes about women from the myths, tellings, memories, and re-tellings jostle with each other, and complicate each other with possibilities. Her collection Vimuktha, translated as The Liberation of Sita, does this almost effortlessly.

From The Liberation of Sita

Sita was sure now. It must be Surpanakha! Yes, it is definitely Surpanakha.

Eighteen years ago… Surpanakha came seeking Rama’s love. What a pretty woman! The wicked prank played by Rama and Lakshmana left her horribly disfigured. Poor thing! Is Surpanakha living in this forest now? So much time has passed since then!

Since Rama had insulted Surpanakha, Ravana wanted to take revenge on Rama by abducting me.

Do women exist only to be used by men to settle their scores? Rama and Lakshmana would not have done this to Surpanakha if they did not know that she was Ravana’s sister. Rama’s objective was to provoke Ravana; his mission, to find a cause to start a quarrel with Ravana, was accomplished through Surpanakha.

It was all politics.

Poor Surpanakha came longing for love. Who will love that ugly woman now that she has lost her ears and nose?

Has she spent all her life in lovelessness?

Has she showered all her love on that garden?

Has she created the garden as an expression of her passion for beauty?

Are these flowers a manifestation of the tenderness of her heart?

Poor Surpanakha!

Lava and Kusa were surprised to see the tears in their mother’s eyes.

‘What is this, Mother? Why are you getting so distressed hearing about some stranger’s ugliness?’

Sita wiped her tears and said with a smile, ‘Will you take me to that garden tomorrow?’

From “The Reunion”

***

From an interview with T. Vijay Kumar: “Let everything that has accumulated over centuries come out…”

How has your understanding of feminism evolved over time?

When I started in the 80s, reading and writing at a feverish pace, I looked at women as a homogenous category—that all women were one, a sort of “workers of the world unite” kind of understanding. Then in the 1990s, caste emerged as a major issue—maybe because of the Karamchedu incident* and the debates that followed. I wrote Aakasamlo Sagam (Half the Sky, 1990), with a Dalit heroine, and with the sense that all women are not the same and that caste plays a major role. Yet, when I did an anthology of feminist poetry Neeli Meghalu (Blue Clouds) in 1993, there weren’t many Dalit women writers in it. There were, in fact, not many of them writing then with a Dalit-feminist consciousness. Yet, I felt that it was a shortcoming of the anthology. Gradually I realised the broad scope of feminism which includes not only just caste, but also several other factors—religion, race, gender (LGBT). Feminism has given me that power to accept, understand and integrate differences. The inclusiveness that I learnt from feminism—I try to express in my writings.

* On 17 July 1985, in Karamchedu village of Prakasam district in Andhra Pradesh, several Dalits belonging to the Madiga caste were killed by upper caste landlords belonging to the Kamma caste.

Do you think the rise of identity movements is a blow to ideological movements?

Ideological movements have reached a stage where if they did not receive that blow, they would have been totally destroyed. That blow was needed and timely. It did not happen accidentally. Identity movements rose out of indifference, neglect. It is true that identity movements created splits initially, and women, Dalits, minorities separated. But I think such separation helps them to know their own identity, strengths and weaknesses. This process will take some time. But perhaps after that they will again arrive at a common identity. Oppressions, for instance, is a common factor since all these movements were born out of oppression. Arriving at an understanding of what is common among their different oppressions may take a long time, but because of technology it might also take a very short time. But whatever is happening now, I feel, is for the good. Let everything come out—even if it is hatred, even if it is hatred arising out of misunderstanding, let everything that has accumulated over centuries come out.

Once it has cleared up, then there will be a realization of your true self. Then the atmosphere will become clearer. I’m optimistic.”

From “Volga: An Interview”, T. Vijay Kumar

Both extracts above are from The Liberation of Sita, translated from the Telugu by T. Vijay Kumar and C. Vijayasree, Harper Perennial, HarperCollins, Delhi, 2016. © Volga © Translation T. Vijay Kumar and C. Vijayasree.

Read Karthik Venkatesh’s Hindi translation of “Eyes” here.

Note: This story was originally published in Stree Shakti (Andhrajyothi) on September 13, 1988. It was then included in the collection Rajakiya Kathalu, 1992. The Hindi translation is from an English translation, Political Stories, translated by Madhu H. Kaza and Ari Sitaramayya, Swetcha Publishers, Hyderabad, 2007.

From a conversation with the Indian Cultural Forum: “The context of my stories is as old as the Ramayana and as new as Nirbhaya or Varnika…”

On The Liberation of Sita:

The short stories featuring in The Liberation of Sita were written over a period of time and published as an anthology in 2010 in Telugu. It was translated into Kannada, Hindi, Tamil, Marathi, Nepali and English. Now Amazon is publishing it in Malayalam, Oriya, and Bengali. I am glad that Ladli media understood my intention in writing the stories—the importance of solidarity and sisterhood among women if they are to realise their potential. The collection also got the Central Sahitya Akademi Award for 2015 and, in the same year, the Translation Award for Tamil from the Sahitya Akademi. But the Ladli award is special because Ladli works for the promotion of gender sensitivity.

On the warning by the thought police:

When my story “Asokam” was published in December 2016, in a magazine which has a huge readership, I received some calls asking me not to write such stories. I was told that they would “cause harm to the nation”. “Asokam” is about Mandodari, the wife of Ravana. I depicted her as a wise woman who dares to argue with Ravana, and defy his order to look and act as a widow after Ravana’s death. There is Mandodari’s rejection of widowhood in the story. There are also arguments about Aryan and Dravidian cultures.

On retelling myths:

In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, reinterpreting mythology has a long history of more than a hundred years. Tripuraneni Ramaswamy Choudary wrote Sambuka Vadha in the early 20th century. This tradition was enthusiastically continued by radical writers like Chalam and Koku. We Telugu people are used to challenging the traditional views expressed in mythology because of reformers such as Kandukuri Veeresa Lingam and Gurajaada Appa Rao, who are also great writers.

On capitalism and patriarchy:

If women’s perspective is understood and put into practice it poses grave danger to capitalist patriarchy. Patriarchy tries its best to remain blind to women’s or gender perspective. We have to be constantly at war with patriarchy, making use of all our tools. For centuries, the Ramayana was used by feudal patriarchs. Now it is our turn to subvert it and give it new meanings and vision. My stories of the Ramayana are relevant in the present day. The context of my stories is as old as the Ramayana and as new as Nirbhaya or Varnika. Capitalism or imperialism use old values and traditions by giving them new shapes to oppress women and men. The shape is skin deep. In essence, the oppression of women, exploiting their bodies and labour, help patriarchy survive, whether it is feudal or capitalist.