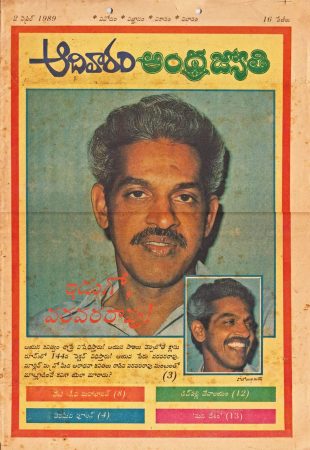

I wouldn’t have been who I am without Varavara Rao (VV), and it is true for the generation I come from and the one that followed. Today’s Telangana wouldn’t have been what it is without him. I have written and spoken about him and his poetry in the past, but now he is on the deathbed, in a faraway hospital, being subjected to retributive torture by the powers that be. Now, with a never-before urgency, I want to speak and write about him, through an interminable torrent of words.

Here, I will attempt to paint the 80 years of his life in seven angles — a rainbow of seven colours that characterise him — a creative writer, teacher, editor, organiser, activist, and lastly, a victim of the state, yet a humane individual.

Part 2

The most immutable and extraordinary part of Varavara Rao’s personality is the teacher he has always been. Instructing, analysing, teaching and studying himself have been integral parts of his living. VV has the ability to enthrall the hearts of his audiences with speeches charged with intellectual rigour, no matter who it is before him — lakhs of people or a single interviewer.

Professionally too, VV is primarily a teacher. Though he started his PhD in 1962, the weak financial situation at his home did not enable him to finish it. In 1964 therefore, VV gave up research and took up a temporary teaching job at Siddipeta College, as a Telugu professor. After leaving it, VV joined as a publication assistant in the Department of Audio Visual Publicity (DAVP) of the Union Ministry of Information and Broadcasting in 1965 in New Delhi.

Also Read: The Making of Varavara Rao: Part One

Having resigned from there too within some months, he returned to the Telugu land with a desire to teach his mother tongue. VV joined as a Telugu teacher at a college in Jadcherla, Mahabubnagar. Two years later in 1968, he became one of the founding faculty members of the Chanda Kanthaiah Memorial (CKM) College of Warangal. Here, he taught Telugu language and literature to thousands until his retirement in 1998.

Besides teaching his students in a classroom, he was popular as an orator too, inspiring many for over fifty years. He traveled extensively across the Telugu land that there is no town that isn’t familiar with VV’s speeches. His initial speeches were at colleges, mainly to his students and employees, at union-meets and in Warangal, during the separate Telangana movement (1968-69). His speeches grew sharper during the Naxalbari-Srikakulam movement. In the politically charged climate that arose in the aftermath of establishing Virasam (Revolutionary Writers’ Association), he would speak at multiple places every month. The Emergency and during 1985-89 when “speech, song and dance were curtailed” and he was imprisoned were the only two times he stayed away from public speaking.

VV gave lectures in almost all the important cities of the country and also led national campaigns against the ruthless repression of the Andhra Pradesh government. Never prioritising his own health, VV travelled and spoke across the state, in scorching summers and torrential rains. His speeches were heard by almost every class of the Telugu society, including rural tenant farmers, the landless poor, urban labourers, mine workers, students, the youth, writers, academics, women, minority communities, adivasi communities, and lawyers. Interspersed with literature and sociopolitical context of the times, his speeches always presented hope towards a better future.

Part 3

Varavara Rao was the editor of a Telugu literary magazine for over 25 years. As mentioned in Part 1, when he was in high school, VV had helped his brothers run a handwritten journal, and during his Master’s in Hyderabad, he was involved in starting a literary magazine. Soon, an organisation called Seven Stars Syndicate roped him in to run a quarterly literary magazine called Navata. Poet Sri Sri agreed to be the Chief Editor of that magazine and contributed a poem called “Jananam Mudaavaham” after VV’s solicitation.

Navata, however, was a failed experiment as he had differences with the editorial team of which he was not made a part of. This failure sparked an urge in him to start a journal for poetry and modern literature exclusively. When he was leaving New Delhi for the job in Mahabubnagar, a friend told him at the railway station, “You are destined to run a literary journal. No one can run a literary magazine in Telugu but you. It’s your duty”.

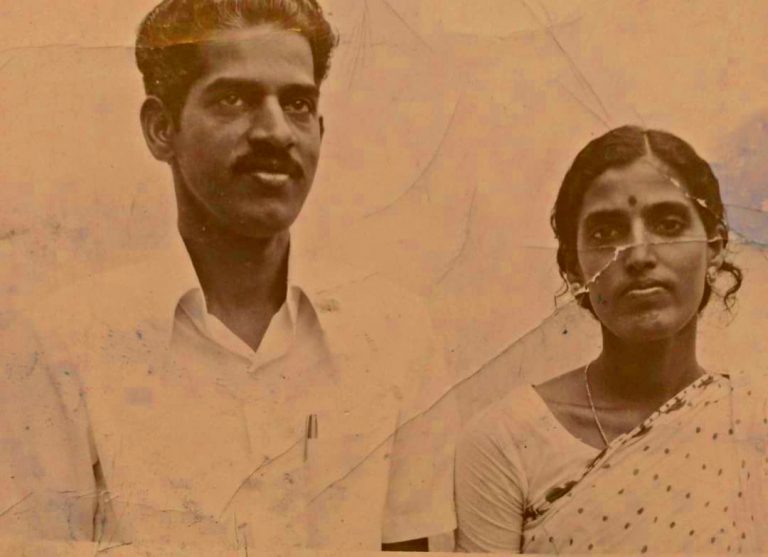

As he returned to Jadcherla in Mahabubnagar, there was a discussion among his poet-friends, including the veteran poet Bal Gangadhar Tilak, to start a journal for poetry. Tilak passed away in the middle of these discussions. The first issue of Srjana was released in his memory in November 1966. Four friends, Ganta Ramanna, a student of philosophy and a long time friend of VV’s, Telugu lecturer Venumuddala Narasimhareddy, and an Economics lecturer Ampasayya Naveen, along with Varavara Rao, buckled up to run Srjana. The journal that began as a quarterly turned into a monthly after 1970. In the following couple of decades, it played the historical role in fuelling the revolutionary movement through literature. Except during the Emergency, which lasted 2 years, and then 4 years between 1985 and 89, Srjana was published consistently till 1992. It inspired many young writers, poets and intellectuals to enter the politically charged literary climate between the 1970s and 80s. The responsibility of running Srjana was of a collective called “Sahitee Mitrulu” (Literary Friends), which was, in fact, single handedly managed by VV. When he was arrested in October 1973, his life-partner Hemalatha became its official publisher, who also suffered two jail terms for taking up the responsibility. VV continued to give it the literary and political direction it needed, along with taking up other tasks like its financial management. Many more literary journals like Vidyullata, Pilupu, Aruna Taara, Kranti, Radical March and Spring Thunder that actively spoke for an alternative culture ran under the guidance of VV.