The pandemic has laid bare the thinly-veiled yet very real fault-lines in our society. A Pandora’s box of evils has been opened and humanity can no longer be assumed to exist in everyone. Every day, 24 hours a day, the news brings stories of the suffering of countless people in the country and the world. Some incidents, however, make us question the very definition of not just civility but humanity itself.

In a harrowing incident, a woman who tested positive for COVID-19 and was admitted to an isolation ward of a government hospital in Gaya, Bihar, alleged that an attending doctor outraged her modesty for two successive nights. She was sent home after she tested negative for the virus, however, her parents observed upon her return that she had become aloof and petrified. The 25-year-old woman eventually succumbed to death due to excessive bleeding. While the investigation is ongoing, the Gaya police have arrested two people who posed as doctors and entered the isolation ward using doctors’ kits.

Earlier in May, a male COVID-19 patient too was sexually assaulted by a doctor in Mumbai’s Wockhardt Hospital. It was reported that the doctor was on his first day of duty when he made untoward physical advances despite resistance from a patient in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) ward.

Another disturbing episode involved a 20-year-old woman who had recently given birth. The woman was sexually assaulted at a private hospital in Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, where she was undergoing treatment for COVID-19. Two staffers, an employee of the sanitation department and a hospital store worker, ruthlessly molested her in an isolation ward on the pretext of taking her samples.

These shocking incidents are a reflection of the weak security systems in our hospitals and a cause of deep concern. One would think that isolation wards and ICUs are safe spaces where patients could hope to recover without fear. However, these incidents bring to the fore the reality that safety is a comfort that patients in India are denied.

Re-examining laws governing safety of COVID-19 patients

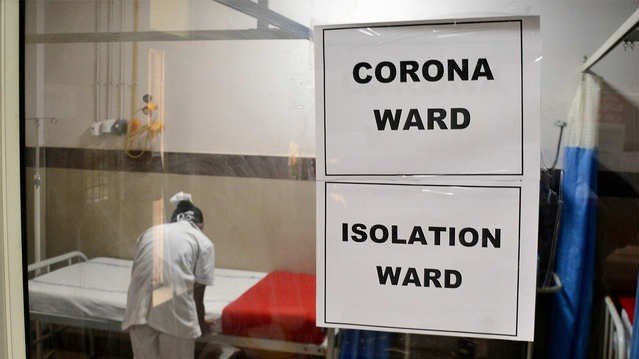

COVID-19 patients in isolation wards are extremely vulnerable. Such patients experience high levels of discomfort and lack of control. Feelings of insecurity are enhanced as they are surrounded by staff in suits and it is difficult to tell who is who. Even first-responders such as the police are unreachable, because they are overburdened and have shifted priorities during the lockdown. Measures to restrict contact and the shift to online discourse have also hindered the ability of civil society groups to provide urgent relief.

These unique circumstances pose several privacy and security concerns for patients. It is therefore imperative that we strengthen existing mechanisms and understand the legal framework around such issues.

Take for example the Prevention of Workplace Sexual Harassment (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (PoSH Act), which makes it mandatory for all workplaces, which includes hospitals, to have in place policies and Internal Committees (ICs) to address workplace sexual harassment. The PoSH Act makes it clear that this law is applicable not only to staff but also to visitors at any workplace. Therefore, both hospital staff and visiting patients are protected under the law. In fact, according to section 2 of the PoSH Act, an “aggrieved person” could be anyone who alleges sexual harassment in relation to a workplace. This implies that ICs at hospitals which deal with sexual harassment complaints from their employees could also deal with complaints from patients.

Setting the tone for other hospitals to follow, in September 2019, the Madhya Pradesh High Court imposed a penalty of Rs. 50,000 on Medanta Hospital, Indore, for failing to constitute an IC in accordance with the law. The harsh reality, however, is that most hospitals continue to function without any such mechanism in place as both vulnerable patients and medical staff lack awareness.

The Medical Council of India (MCI) too, with the approval of the central government, has prescribed the Indian Medical Council (Professional Conduct, Etiquette and Ethics) Regulations, 2002. This includes the Code of Medical Ethics that places medical professionals at the epitome of respect, honour and character requiring them to render service devotedly, diligently and with dignity. The Code imposes liability on medical practitioners to “aid in safeguarding the profession against admission to those who are deficient in moral character”.

Regulation 6.6 goes so far as to stipulate that a medical practitioner shall not “aid or abet torture” nor “be party to infliction of mental or physical trauma”. Medical practitioners are also forbidden from concealing torture if inflicted by some other person or agency in clear violation of human rights. Further, these regulations specify acts committed by medical practitioners which could constitute professional misconduct. Regulation 7.4 provides that an abuse of professional position by committing adultery, improper conduct with a patient, or maintaining an improper association with a patient would render a physician liable for disciplinary action.

Although the degree of association is not defined under the regulations, it may vary from consensual sexual intercourse to any unwanted degree of physical contact. The regulations also make it clear that in such cases, consent of any of the parties is no defence to escape the liability for punishment.

Medical Councils are given wide powers to take disciplinary action against medical practitioners. Regulation 8.2 stipulates that if a medical practitioner is found to be guilty of committing professional misconduct, the appropriate State Medical Council may award such punishment as may be deemed necessary. Moreover, disciplinary action may also be taken if they are convicted by a court of law for offences involving moral turpitude or any criminal acts.

Punishment could include direct removal of the delinquent’s name from the register of registered medical practitioners, either for good or for a specified period of time. The regulation further states that deletion of a name from the register shall be widely-publicised in the local press as well as in the publications of various medical associations or societies.

Evidently, the regulations provide a strong foundation for protection of patients’ rights. However, as comprehensive as these regulations may be, the MCI has a dismal record of enforcement of its own guidelines. The underlying reason for poor implementation may be that the state medical councils are entities independent of the MCI and have no responsibility towards it. Besides, the medical fraternity has also shown reluctance towards implementation of the regulations.

Recently, the inclusion of healthcare or medical services under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, (CPA) was hotly debated. In August 2019, the old CPA of 1986 was repealed and replaced by the CPA, 2019. While the 1986 Act originally had no express provisions carved out for healthcare or medical services, provisions of the old Act were applied to medical services through judicial interpretation. The Supreme Court of India, in the case of Indian Medical Association vs. VP Shantha, 1995, widened the ambit of Section 2(1)(o) of the Act by holding that all chargeable services provided by medical practitioners and hospitals, including insurance would amount to “services” against which legally enforceable action may be taken under the Act. This holding of the apex court is well-reasoned—if basic goods and services for which a consideration is paid accord protection under the Act, why should healthcare be excluded?

It is interesting to note that the Consumer Protection Bill, 2018 envisaged the inclusion of healthcare as a part of “services”. However, it was eventually excluded from the list owing to continuous criticism and demands from various medical organisations. While many may disagree, it would have been a progressive move to include healthcare in the list of “services” under the Act as it would provide a faster mechanism to ensure that aggrieved patients have remedies against malpractices of medical practitioners and hospitals. The burden has now shifted to courts rather than state or national consumer forums, making the process more time-consuming and tedious.

The Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897, which was first enacted to tackle the bubonic plague in Bombay gave unfettered powers to the authorities to examine people at will and detain suspects. At the time, the act was highly criticised for sanctioning gross violation of human rights without limitations. All of two pages and six sections, somehow this Act still continues to find relevance in tackling health emergencies today.

Recently, the government of India passed an ordinance to amend the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897, which was brought to effect in the wake of increased incidents of harassment and violent attacks on doctors and healthcare professionals amid the crisis. While the amendment came as a welcome move, the Act has largely failed to address issues arising out of a modern-day pandemic and particularly lacks provisions to protect patients’ rights.

Another central legislation which regulates hospitals, healthcare and medical services in India is the Clinical Establishment (Registration & Regulation) Act, 2010. While it does not by any means provide gold standards of healthcare, it prescribes minimum standards of medical services to be followed by clinical establishments in the country. Even in its weakest form, states have largely refrained from adopting the Act—merely 11 states and all Union Territories (except Delhi) have adopted it so far. Unfortunately, many of those who have adopted the Act have also failed to effectively implement it.

Besides, the fact that the Act applies only to government hospitals is a significant limitation. When state governments (such as Haryana in 2019 and Punjab amid COVID-19 crisis) tried to rope in private hospitals under the ambit of the Act, the move was strongly opposed by organisations and state chapters of the Indian Medical Association.

Bridging the gaps

A re-look at the governing laws shows that legislations, no matter how well-intended, are rendered largely ineffective if they are not adequately implemented by those to whom they apply. These laws also make it clear that hospitals cannot turn a blind eye to protection of patients’ rights and that medical professionals being in positions of trust owe ethical responsibilities to their patients. So far, a limited number of incidents involving sexual abuse of COVID-19 patients have been reported in the media, however, in all probability, many such incidents go unreported. In light of these shocking incidents it has become all the more important that governments and hospitals take appropriate measures before it is too late.

Steps ought to be taken to ensure that both hospital staff and patients are wary of existing laws and the serious repercussions that follow any form of sexual harassment. Hospital management must make every effort to comply with the PoSH Act and have in place appropriate ICs for timely redress in any sexual harassment complaint. Moreover, in light of the sexual assault by a doctor of a male patient, amending the law to make it applicable across genders should be considered. If not, hospitals should at least endeavour to adopt gender neutral sexual harassment policies. Also, the process of lodging complaints and holding inquiries must be eased to ensure convenience to all stakeholders. So far as possible, proceedings should be conducted through video conferencing to ensure that timelines envisaged under the Act are duly met.

While health is a state subject and states need to actively adopt progressive legislations, the central government too should step in to ensure strict compliance. For example, the Centre should amend the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897 and CPA, 2019, to address lacunae in the existing legal framework so that safety of COVID-19 patients is not compromised in the future. The judiciary as well as the National Human Rights Commissions and National Commission for Women should play an active role by taking suo moto cognizance of matters involving sexual abuse of patients.

Hospitals should also endeavour to adopt in letter and spirit, the Charter of Patients’ Rights, which seeks to protect patient’s rights such as human dignity, privacy, safety and security among others. What appeared to be a well-intentioned, promising document has remained toothless as many states have refrained from adopting it.

Additionally, all clinical establishments testing and treating COVID-19 patients must enhance and tightly enforce their security systems. Hospitals must monitor and ensure access control by mandating identification checks. Requiring doctors, medical attendants and other hospital staff to wear an identification band with their name and other important details around their wrist could make patients feel safer. Hospitals must require everyone in the premises to wear appropriate identification bands at all times so that everybody can be easily identified.

Research shows that direct consequences of infection or the restrictive measures imposed to curtail the spread of infection may cause anxiety, depression, insomnia or psychological distress which could in turn result in escalation of incidents of sexual violence. To address this, it is crucial to have in place a mental health framework for COVID-19 patients and doctors. Use of digital platforms and tele-psychiatry services could facilitate prompt mental health support.

Time and again, the Supreme Court has upheld the principle that the right to life entails the right to live with human dignity which extends much beyond “mere animal existence”. Under the garb of the pandemic, state governments and hospitals cannot abdicate their responsibility to assure protection to patients who are already distressed.

There is no denying that it is important to focus our attention and resources on stopping the spread of COVID-19, however, we must not lose sight of emerging issues, which if ignored, could become a pandemic of their own.