Days, weeks, months, an indeterminate amount of time as the world seems paralysed by the journey of SARS-CoV-2. The lack of certainty increases the anxiety. This virus, as Arundhati Roy writes, ‘seeks proliferation, not profit, and has, therefore, inadvertently, to some extent, reversed the direction of the flow [of capital]. It has mocked immigration controls, biometrics, digital surveillance and every other kind of data analytics, and struck hardest – thus far – in the richest, most powerful nations of the world, bringing the engine of capitalism to a juddering halt’. Lockdowns have now become almost universal, the planet more silent, the birdsong richer. Arundhati Roy’s cautionary ‘thus far’ is significant as the virus makes its circuit deep into zones of extreme deprivation, into the slumlands of Dharavi (India) and Cidade de Deus (Brazil).

A major United Nations report with the hopeful title ‘Shared Responsibility, Global Solidarity’ says that the global pandemic ‘is attacking societies at their core’. Social and state institutions have been so hollowed out in many parts of the world that they are simply not capable of managing either the health, social, or economic crisis. The International Monetary Fund’s Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva said that there is no possibility of economic recovery before 2021. We are in April 2020; it is almost as if the entire calendar year of 2020 has been cancelled.

One thing seems to have united a range of people: total bewilderment at the failure of the bourgeois order, and a significant shift in the belief in the ‘free market’ to properly allocate resources. Even the Financial Times takes this view:

Radical reforms — reversing the prevailing policy direction of the last four decades — will need to be put on the table. Governments will have to accept a more active role in the economy. They must see public services as investments rather than liabilities, and look for ways to make labour markets less insecure. Redistribution will again be on the agenda; the privileges of the elderly and wealthy in question. Policies until recently considered eccentric, such as basic income and wealth taxes, will have to be in the mix.

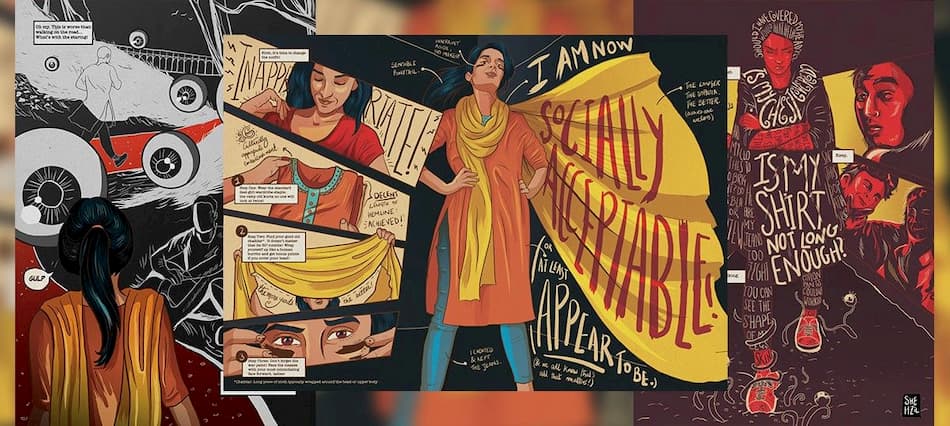

Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, the UN Under-Secretary General and head of UN Women, wrote recently that the global pandemic ‘is a profound shock to our societies and economies, exposing the deficiencies of public and private arrangements that currently function only if women play multiple and unpaid roles’. This is a sharp statement and bears serious reflection.

Health care workers.

Almost three in four essential frontline workers – from medical personnel to medical laundry workers – are women. It is one thing to bang pots and pans to celebrate these workers, and another to accept their long-standing push for unionisation, for higher wages and better working conditions, and for leadership in their sectors of work. Almost all administrators in the hospital field globally are men.

In India, the weight of any health care emergency is borne primarily by the 990,000 Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) workers, by the Anganwadi or childcare workers, and by the Auxiliary Nurse Midwives. These workers – almost entirely women – are severely underpaid (their low salaries often held for months on end), undertrained, and are denied even the most basic worker protections (they are treated as ‘honorary volunteers’, a ludicrous category deployed by the government). Last year, ASHA workers were involved in a cycle of struggles to improve their employment conditions; apart from small victories here and there, they were largely disregarded (for more on this, see our interview in Dossier no. 18 in July 2019 with K. Hemalata, President of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions). During this pandemic, it is the ASHA and Anganwadi workers who are going house to house checking on families, doing so without basic protection (such as masks and hand sanitizer). These are the frontline public health workers who are now being rhetorically celebrated, but who are not given the basic protections of unionisation, of job security, and of adequate wages.

Reinforced gender roles.

Two years ago, the International Labour Organisation published a study that showed that women perform 76.2% of unpaid care work – three times higher than the rate for men. The ILO found that ‘attitudes towards the gender division of paid and unpaid care work are changing but the “male breadwinner” family model remains very much engrained within societies, along with the women’s caring role in the family continuing to be central’. This is the undisputed situation during ‘normal’ times; in the time of the pandemic, this structural inequality and these cultural biases become a torment.

Aspects of care work that had been lightened by the institutions and structures of society are now shut down. Schools are closed, so children are at home with pressure for them to be home-schooled; elders are not able to meet each other in parks, so they are to be entertained and tended to at home. Shopping is more onerous, and cleaning is more essential – all tasks that evidence suggests fall on the shoulders of women.

Violence against women.

Before the CoronaShock, on average 137 women across the world were killed by a family member every day. This is a shocking number. As Rita Segato put it, not only have incidences of violence against women increased in frequency since the CoronaShock; they have also increased in their cruelty, as neo-fascist ideas of female subordination eclipse more enlightened ideas about women’s emancipation. In Argentina, the slogan el femicido no se toma cuarentena, or ‘femicide does not quarantine’, clearly points to the violence that has been inflamed by the global lockdown. In every single country, reports come in of increased violence against women. Support lines are overflowing, shelters cannot be reached.

In Trento (Italy), the prosecutor Sandro Raimondi declared that in a case of violence against women, the abuser should leave the home, not the victim. The Italian Confederation of Labour said, ‘Confinement at home because of the coronavirus is difficult for everyone, but it becomes a real nightmare for women victims of gender-based violence’. Such creative approaches against violence against women are necessary.

The Coordinadora Feminista 8M of Chile has produced a Feminist Emergency Plan for the Coronavirus Crisis. This plan – which resembles in some elements the platform created by the International Assembly of the Peoples and Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research – has four essential elements:

- Develop strategies for collective feminist mutual aid. Build solidarity and mutual aid networks that fight against individualism and respect social distancing. First, conduct surveys of neighbourhoods. Second, build teams to care for children. Third, mobilise health professionals to assist the community.

- Confront patriarchal violence. Build a mechanism to react collectively to cases of violence against women. Produce neighbourhood-based emergency plans for women and children to leave dangerous situations, such as by the creation of emergency phone hotlines and by the opening of shelters.

- Call for a general ‘strike for life’. Strike against all productive activities that are not oriented around health care; defend the right to stay at home during the pandemic and produce a system of remuneration for those who are carrying out the various forms of labour – such as essential and often invisible care work. Demand safe working conditions for essential workers, particularly in the professions of healthcare and transportation.

- Demand emergency measures that put our care first, not their profits. Life is priceless; therefore demand paid medical leave, free childcare, house arrest for those who are in prisons, freezing of prices for basic goods and sanitary products, planned production for social needs (rather than for profit), compensation for all caregivers (formal and informal), free quality health care for all, suspension of debts and dividends, free access to water and electricity, and a prohibition against the firing of workers.

Each of these points is utterly intuitive, being useful not only in Latin America but across the globe. But this Emergency Plan is only – as the Algerian poet Rabi’a Jalti puts it in Shizufriniya (Schizophrenia) – one street; there is always that other street.

I have become two streets.

One looks over the apricot tree and narcissus,

And the morning of poems.

It enters the sea of language.

And the other

Is he whose name is hung on the horizon and the colour of bread,

Whose face has fenced in all directions,

Whose breaths have sealed all circles.

It nearly chokes me.

It is that street that chokes which has led the local government in Durban (South Africa) to forcibly evict shack dwellers. Because we were thinking of the other street, Arundhati Roy, Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein, Yanis Varoufakis, and I wrote this objection. It is along this other street that people hunger for land, not only to build their homes but also to farm them. From South Africa to India to Brazil, hunger drives land hunger.

In our latest publication, Dossier no. 27 (April 2020), ‘Popular Agrarian Reform and the Struggle for Land in Brazil’, we show how this land hunger motivates a struggle not only for land, but for social transformation. Our São Paulo office writes that at the core of this struggle is ‘the refashioning of social relations – including the reconstruction of gender relations and the confrontation of machismo and homophobia, for example – and the demand for access to education in rural areas at all levels’.

We will be sharing more about the struggle for land in next week’s newsletter, which you can subscribe to on our website in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Hindi, French, Mandarin, Russian, and German.

Before CoronaShock, while you read this newsletter, two femicides would have occurred somewhere in the world; during CoronaShock, the number is higher. This must end.