It is clear by now that the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns will leave a huge trail of losses in the health sector as well as the global economy. Obviously, the Indian economy will also take a huge hit, with the costs largely borne by the poor. This article analyses the scale of the impact on the economy using quantitative models. The analysis shows that for the fifth-largest economy in the world, India has comparatively one of the smallest financial relief packages.

Media reports since the second week of March have carried news of increasingly-escalating estimates of economic losses. According to a UNCTAD analysis dated 9 March, the pandemic may cost the world economy $1 trillion in 2020. By 26 March, the UNCTAD revised its analysis and stated that “the negative impact will be worse than previously projected”.

In India, for an economy that was already in a downward spiral, the impact of COVID-19 and the lockdown will be severe. There have been demands on the government to declare an economic stimulus package.

However, to be able to formulate an adequate economic response to such an impact, it is first necessary to assess its scale. It is difficult to do so to a very high degree of accuracy given the interdependence of various sectors on each other as well as the paucity of data about the large informal segment of the Indian economy. However, it is possible to arrive at some measure of the current economic activity and the likely impact the lockdown will have on it in the immediate future.

In an era of black-box non-linear computable general equilibrium models, simpler tools that were at one time promoted by economists and policymakers, especially for planning in developing economies, have fallen by the wayside. Simple Input-Output (IO) analyses can provide much more direct and useful policy insights than complex general equilibrium models, especially given that the deviation from a supply-demand ‘equilibrium’ is likely to be very high at this point.

This article explains the results of a simple IO analysis done to arrive at a measure of the economic impact of COVID-19.

An IO analysis is a simple method devised by Wassily Leontief that allows a linear computation of the overall economic impact through a consideration of all the interdependencies in the economy, along with the sum total of wages, profits, savings, and expenditures in each sector and by each section of consumers (households, government etc.).

The use of IO analysis in the Indian economy is constrained by the fact that after it disbanded the Planning Commission and substituted it by the NITI Aayog, the government has not published an input-output matrix for the country. The last available official matrix is for 2007-08. While the Government does publish the national account statistics, unlike an input-output table, these do not provide information on the structural dependence of different sectors of the economy on each other. The impact of an event, either a short-term one like, say, a cyclone or a long-drawn-out one, like this lockdown, affects different sectors of the economy directly as well as indirectly.

The direct impact is more straightforward to calculate, while the indirect impact is more difficult to calculate, as it results from the interdependence of sectors. For example, the reduction in demand for transportation will not only impact the transportation sector itself but also other sectors such as manufacturing and agriculture.

For the results explained in this article, the World Input Output Database, which provides IO tables for 48 countries for 2014 was used to estimate the aggregate economic output for India in 2020. This is a pre-COVID-19 estimate. It was then assumed that each sector of the economy will lose a certain number of workdays because of the lockdown. Assuming that the annual output in each sector is distributed more or less uniformly across the year, it is then possible to calculate the total output loss. Using the estimated output loss, a new post-COVID-19 input-output table can be constructed for India for 2020.

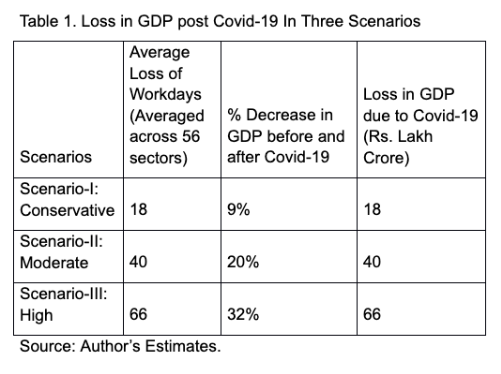

The GDP loss due to COVID-19 can be assessed from this new input-output table. Table 1 shows the results from such an analysis for three scenarios; conservative, moderate and high. The conservative scenario assumes that very less number of workdays will be lost across each sector (for example, more in transportation and services and less in others). The moderate scenario assumes that more workdays will be lost and the high scenario assumes a large number of work days lost.

The conservative scenario from the table is not the reality that obtains in India today, as a minimum of 21 days of work will be lost in many sectors. However, many studies clearly show that a 21-day lockdown will be ineffective unless the government has an alternative strategy to contain the contagion. In my view, India may be somewhere between the second and third scenarios. In other words, the total loss of output would conservatively be between Rs. 40 and Rs. 66 lakh crore, or about 20 to 32% of the GDP.

The scale of the crisis of both demand and supply, and the attendant humanitarian crisis that a prolonged lockdown will cause, will therefore be tremendous. Some measure of lockdown will certainly have to be in place. However, the government needs to have a sound plan to alleviate the human and economic cost of both COVID-19 and the lockdown measures to tackle it. This plan has to be preceded by a rigorous quantitative and qualitative assessment of the impact, the potential extent of the fiscal support that will be needed, methods of mobilising this support, and the manner in which it should be directed, so as to avert a humanitarian crisis of gigantic proportions.

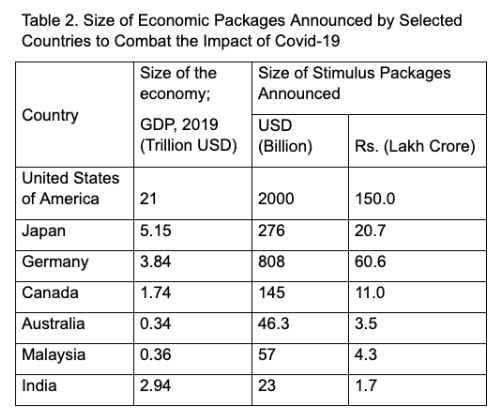

Unfortunately, the government’s current handling of the rapidly unfolding economic fallout of COVID-19 does not instil much confidence that a sound plan will be forthcoming anytime soon. The numbers speak for themselves. The fifth-largest economy has one of the measliest fiscal packages to offer in this situation (See Table 2 for a comparison of India’s financial relief package with economic stimulus measures offered by other major economies). While this note estimates the total impact of the pandemic at between Rs. 40 and Rs. 66 lakh crore, the economic package announced by the government is only Rs 1.7 lakh crore.

Economies smaller than India have announced much larger relief measures. There is no doubt that government spending in India will have to be scaled up substantially, both in the short and long term, given that the country may be staring at an output loss of at least Rs. 40 lakh crore. But scaling up expenditure alone will also not help. The careful planning and execution of fiscal measures directed towards protecting the most vulnerable sections of the population and eventually kick-starting economic activity is extremely essential. If the government adheres to its prevailing ideology of fiscal austerity, tendency of bailing out corporations, providing tax exemptions for the rich and cutting subsidies to the poor, it will only make the crisis worse.