The Savarkar Sahitya Sammelan, which was organised with much fanfare in the national capital, proved to be rather a tame affair. With the talk of Savarkar being posthumously honoured with the Bharat Ratna in the air, the two-day gathering was considered important.

Home Minister Amit Shah absented himself from the event, supposedly because of the worsening situation in Delhi. It is a different matter that he himself has received condemnation from all quarters for the apathy and inaction he displayed. As BJP president JP Nadda’s video message substituted for his actual physical self, it was left to junior ministers to sing paens to “Veer” Savarkar.

Well, as of now, it is a bit difficult to decipher whether the absence of senior leaders was inadvertent or deliberate, but it was an interesting coincidence that while the BJP and its karykartas were engaged in glorifying “freedom fighter, thinker and visionary” Savarkar who apparently “didn’t get what he deserved”, a leading Marathi newspaper and few other publications made an interesting expose, which put the saffrons on the defensive vis-a-vis Savarkar.

It was revealed that the list of ‘Great National Leaders’ prepared by the state government of Maharashtra does not include Savarkar’s name. Interestingly, the list includes Mahatma Gandhi, President Ramnath Kovind and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, but no Savarkar.

What is the significance of such a list?

It becomes mandatory for the government and semi-government offices to put up the photographs of the dignitaries in this list in their offices. Also, this list is updated from time to time, the last time on 11 September 2017, when the BJP-Shiv Sena coalition government headed by Devendra Phadnavis was in power. So the exclusion of Savarkar becomes even more questionable, for the saffrons have handled power in the state earlier too. The Shiv Sena and BJP shared power in the late nineties 1995 to 99, with the former the senior partner of the alliance.

When Fadnavis was asked why Savarkar was excluded—an issue on which he has been using to drive a wedge within the ruling alliance in the state—he admitted that it was a “mistake”. It seems the government led by him “forgot” to include him.

Even a layperson would find this explanation rather unconvincing. It is difficult to believe that the saffron fraternity simply disremembered Savarkar during both their tenures in power and suddenly woke up to his memories when they found themselves occupying the Opposition benches.

It seems a clear case of selective amnesia.

This is definitely not the first time that saffrons had displayed their open disinterest in Savarkar’s name.

The removal of Savarkar’s quotes from the Cellular Jail had made headlines during the UPA-I regime. At the time, Vikram Savarkar, Savarkar’s nephew had accused the senior leaders of the BJP for “keeping mum despite noticing the removal of his uncle’s quotations from Port Blair’s Cellular Jail”. According to him, Ram Kapse, the then Lieutenant-Governor of Andaman and Nicobar and former MP Ram Naik (both BJP workers) “..did not utter a word when the plaque was removed.” The report further states, “…he is not surprised at BJP’s lack of interest in Savarkar. ‘We know very well that the BJP and RSS did not appreciate his [Savarkar’s] philosophy.’” And the report states Vikram Savarkar’s belief that the BJP’s sudden love for Savarkar is an “…effort to woo voters for the Assembly elections in Maharashtra.”

A journey down memory lane also tells us how setting up a Savarkar memorial at the Marseilles in France had similarly boomeranged on them. Marseilles had a special significance in Savarkar’s life. It was here that he had jumped off a British ship in 1909 and escaped to the French coast while he was being brought to India from London. Savarkar swam ashore but was arrested later in Marseilles.

On the eve of 2009 elections to the Maharashtra Assembly Gopinath Munde, then a senior BJP leader, had raised this issue in Parliament, underlining that the Mayor of Marseilles had agreed to provide land for the memorial and had sought consent of the Indian government, to which the government had not responded so far. He had hoped that the BJP would be able to score a point vis-a-vis the Congress-NCP coalition. But in his hurry to put the then ruling dispensation on the mat, Munde forgot to note a very small detail of the correspondence between the Mayor of Marseilles and the government of India.

According to ‘Swatantryaveer Savarkar Seva Kendra’, Jean Claude, the Mayor did send a letter to the Prime Minister expressing his willingness to address the concerns of Savarkar’s followers, but it had reached the Prime Minister’s Office exactly 11 years back on 8 July 1998, when Vajpayee had been the Prime Minister and he had not acted on it. This file had been gathering dust all these years.

This distrust and disinterest between the Sangh parivar and Savarkar is not a one-day affair but has a long history.

The trajectory of the Hindu Mahasabha under the leadership of Savarkar and the way in which the RSS unfolded itself during colonial period makes it quite clear that the differences in priorities between the two organisations existed from the day Savarkar was elected president of the Hindu Mahasabha after his release from jail in 1937. In his sympathetic study of the RSS, The Brotherhood in Saffron, The RSS and Hindu Revivalism, the authors Walter K Andersen and Shridhar D Damle clearly explain that Savarkar’s emphasis was on turning the Mahasabha into a political party in opposition to the Congress when the Hedgewars had already decided to insulate RSS from active politics and concentrate on “cultural” work.

Hedgewar and, later Golwalkar, did not want to be associated with a formation whose confrontational activities would place the RSS in direct opposition to the Congress. According to him there were apprehensions regarding each other’s role in the Hindu Unification Movement. The souring of relations between the two organisations is visible in an angry letter issued by Savarkar’s office in 1940, advising that “…When there is such a serious conflict at a particular locality between any of the branches of the Sangh RSS and the Hindu Sabhaites that actual preaching is carried out against the Hindu Mahasabha…then the Hindu Sabhaites should better leave the Sangh…and start their own Hindu Sabha volunteer corps.” This is recorded in the letter from Savarkar to SL Mishra on 3 March 1943, in the Savarkar files, Bombay.

The earlier Hindu Mahasabha leaders prior to Savarkar were expecting that RSS would work as a “youth organisation” of the “parent body”. But that plan did not materialise and then Hindu Mahasabha under Savarkar’s leadership was forced to form Ram Sena in its place. Savarkar’s increasing frustration with RSS’ ‘docile’ nature and its activities was evident in the famous statement he made in the early forties unleashing his attack on RSS without mincing words:

“The epitaph for the RSS volunteer will be that he was born, he joined the RSS and died without accomplishing anything,” as recorded in DV Kelkar’s The RSS, in the Economic Weekly on 4 February 1950.

It is now history that in 1942 when the British were engaged in World War-II and the Congress’s call for Quit India was reverberating throughout India, thousands of people engaged in government jobs, including police and military, quit in protest of the British regime.

The mass upsurge of the Indian people once again could not compel both these organisations to chart a unified path. Of course, there was one commonality and it was their refusal to join the anti-colonial mass upsurge. Thus while the RSS preferred to keep itself aloof from the Quit India movement and concentrate on its “cultural” agenda, Savarkar went a step further. At that time he preferred to take a tour of India asking Hindu youth to join the military with a call to “militarise the Hindus, Hinduise the nation”.

Even Independence could not bring about any qualitative improvement in the relationship between Savarkar and the rest of RSS led by Golwalkar. In fact, the killing of Gandhi as part of a conspiracy hatched by Hindutva forces and the consequent government crackdown on RSS and the Hindu Mahasabha, and the long and winding court proceedings that followed, further soured relations between the two. RSS’s vainglorious attempts to save itself from the aftermath, Golwalkar’s petitions to Sardar Patel to lift the ban on RSS, coupled with its inaction as far as the court case against Savarkar and his other comrades was concerned, proved to be the last straw.

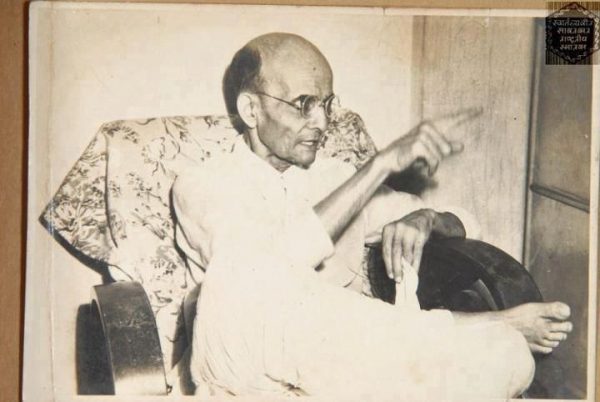

The fifties saw the RSS attempt to build a mass political party of its own in the form of Jan Sangh, with a senior ex-Hindu Mahasabha leader Syama Prasad Mukherjee in the leading position. It was a time when both the Jana Sangh and the Hindu Mahasabha contested for the same political space in an ambience which was not conducive for either of them. It was clear to even a layperson that the RSS as well as Jana Sangh were maintaining a distance from Savarkar. In fact, Savarkar died a lonely man abhorred by the very people who once called him the pioneer theoretician of the project of Hindu Rashtra.

Politics is a game of the impossible.

The Sangh parivar, which never enjoyed a smooth relationship with Vinayak Damodar Savarkar when alive, now wants us to believe that it is the true and the only heir to his legacy. It is a different matter that cracks surface every now and then when this legacy is being constructed.