I first heard of Jiban Narah from my poet-friend Anvar Ali in August 1997. He had met Jiban at Rabindra Bhavan, Sahitya Akademi Head Office, during the Young Poets’ Meet in connection with the Golden Jubilee of India’s Independence. The two had apparently hit it off wonderfully from that very first meeting, resulting in Anvar Ali writing about him in the trendy literary and cultural Malayalam journal Kalakaumudi immediately after, introducing him to Malayalam poetry lovers. In later years, this followed with Jiban visiting Kerala, where fellow poets Anvar Ali, Anita Thampi, PP Ramachandran, TP Rajeevan (who has sadly left us on 2nd November 2022), and a few others took him around and familiarised him with the young poetry scene in Kerala.

Jiban Narah continues to be a warm presence in Kerala’s literary consciousness. He participated in a major poetry festival here, The Pattambi Poetry Carnival, in its 2022 Edition where Anvar Ali interviewed him.

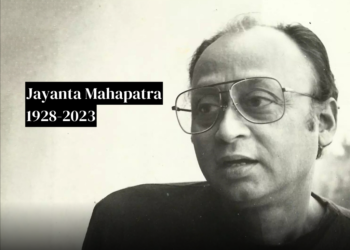

All this while, he was also spreading his poetic presence in other Indian languages. The revered poet-patriarch Jayanta Mahapatra had read and edited the manuscript of his The Buddha and Other Poems.

During my more than two decades’ long presence at Sahitya Akademi, editing Indian Literature, I have had several occasions to be in the company of the poet himself and enjoy his engaging poetry, as well. In 2019, on my second visit to Guwahati to attend the Guwahati Literary Festival, my wife and I travelled to Nagaon to Jiban’s village, to meet him at his home, where we met his family and friends.

Jiban Narah is 53 years old now, having been born in 1970, in Morangial village, in the Golaghat district of Assam. He has been living in Nagaon for several years, teaching in a college there. He is steeped in the culture of the Brahmaputra Valley. His own Mising tribe and several other tribes that inhabit the region, as well as the other Assamese people have been deeply influenced by this culture. The Mising, evolved and nurtured around the Brahmaputra, are seriously conscious about their specific place in the cultural history of the Valley. Jiban’s poetry is an epitome of this consciousness. However, instead of being hemmed in by his tribal identity, Jiban has succeeded in expanding his poetic presence at the national level. Yet, he has retained his Mising links throughout and has pegged many of his poems to them. The iconic Assamese literary journal Gariyoshi had discovered Jiban’s talent early, and he has never looked back.

Jiban Narah writes in Assamese, although he was born into the Mising tribe, which has its own language. Asked by Anvar Ali in the 2022 interview at Pattambi Poetry Carnival, as to why he did not write poetry in his native Mising language, Jiban Narah said:

“This was a kind of compulsion when no alternative was available at the time of my schooling. Now I feel proud to be an inheritor of two cultures –one to which I was born and the other in which I have been brought up. There was little chance in choosing my Mising tongue even in school. The irony is that the Mising language is yet to evolve competently from its status of a dialect to the standard medium of instruction with the entire support system. Thus, my dialect though rich in folk aesthetics has remained a dialect. Of all the ethnic languages only the Bodo language has evolved to that literary status winning Sahitya Academy Award. So I enjoy my identity as an Assamese poet from a resourceful Mising riparian community.”

Jiban’s poetry reached several other Indian languages through translation very early in his career. Anvar Ali had translated him into Malayalam as early as 1997. His poems have been translated into English, Bengali, Tamil, Hindi, Marathi, Oriya, Gujarati, and Manipuri. Over the last three decades, he has read his poetry all over the country at poets’ meets organised by Sahitya Akademi and many other significant literary organizations.

On 31st March 2023, he received the first Yapanchitra National Poetry Award from the Yapanchitra Foundation, Kolkata. His bio in the invitation to the award function rightly describes him thus:

‘Nineties poet Jiban Narah has emerged as the true successor of the legacy of Nilmoni Phukan, Harekrishna Dekha and Hiren Bhattacharya. His poetry has crossed the boundaries of his home state Assam to receive appreciation from all over India and has reached the shores of the world outside….’

Narah has six books of poems in Assamese, one novel, a collection of personal essays, and a compilation of Mising poetry translated into Assamese. His book of Mising folk poetry translated into English, titled Listen My Flower Bud: Mising Tribal Oral Poetry of Assam (2008), was published by Sahitya Akademi. The Buddha and Other Poems (2009), a collection of English translations of his poems, was published by TP Rajeevan’s publishing house Monsoon Editions, Kozhikode, Kerala

Illustrious Assamese poets like Navakanta Barua and Kabin Phukan, senior critics, academics and translators like Hiren Gohain, Pradip Acharya, Geetashree Tamulay, Prabhat Bora, and the doyen of Modern English poetry in India, Jayanta Mahapatra, have evaluated and recognised Jiban’s poetry as uniquely brilliant.

In just two sentences. K. Satchidnandan, renowned poet, former editor of Indian Literature, and former Secretary of Sahitya Akademi, presents Jiban Narah to the world audience thus in his Introduction (i) to The Orange Hill, Jiban’s second collection in English translation:

‘Jiban Narah is easily one of the finest Indian poets writing in Asomiya today. Though heir to the great modernist tradition of Navakanta Barua and Nilmani Phukan in his language, Jiban creates a poetic world of his own as he also inherits the older Vaishnavite Bhakti tradition of Sankardeva and Madhavdeva as well as the rich oral tradition of Mising and he works his way through tales from Bhagavata and Mising myths and picks his colourful images from his riverine tribe that lives in bamboo stilt-houses and thrives on agriculture.’

Both Prof. Satchidanandan and I depend entirely on English translations of Jiban’s poems to form an opinion about them. Let me humbly admit that I am proceeding to write about Jiban’s poetry while being aware of my constraints of not knowing Assamese culture, including its language and literature, adequately.

As is well-known, poetry written in any of our languages is well-nigh impossible to be translated successfully into English as poetry is that last frontier a poet pushes, making new space in their respective language and literature, and that fresh creation would always elude any kind of transference into a standardised language.

However, in Jiban’s case, the poetic content is so strong that even after the ‘loss in translation’, what is left is its worth in gold or diamond! Reading the poems of the collection The Orange Hill, I was awestruck by the strength of his poetic expression in many a poem.

![]()

From my readings of the English translations of Jiban’s poetry, much like Chinese and Japanese symbolist poetry, and unlike the seemingly esoteric yet intense French symbolist poetry, as opined by Kabin Phukan, Jiban has drawn from his native culture, and his poetry has arrived where it has as his natural expression.

Geetashree Tamulay likens the craft of his poem ‘Colours’ to that of the French symbolist Rimbaud. Pradip Acharya remarkably notes that ‘…the faith on nature-dependence nurtured by Jiban Narah in the mid-nineties is significant both for literature and society’. He further observes that this oneness with nature is the keystone of post-modernist literature as demonstrated by Garcia Marquez, Salman Rushdie, and Orhan Pamuk. Jiban being credited with such an important role in Assamese literature by a venerable critic and translator like Pradip Acharya speaks volumes for the importance of this poet.

The hallowed poet Navakanta Barua says of his poetry, ‘Jiban Narah shows that the folk is part of us and folkways make direct inroads into modern poetry and inform his idiom which is regular and catchy…. He is a poet of distinctive character. He brought in a new, sensuous quality to the otherwise intellectual modernity of many of his contemporaries’ (The Book Review, Vol. XXI).

I will share some insights on samples of his poetry I have culled from the available translations of his poems into English. The culture-specific poems will have to be understood by readers in the context of the specific cultural markers the poet identifies with, using which he presents his poems. The poems without specific cultural markers can be described as post-modern poems. (I use term ‘post-modern’ here merely to indicate the conglomeration of writings that comes after the era of modernism was over in a particular Indian language, so as not to confuse it with the western experience of the ‘postmodern’, which is largely out of the picture in our specific Indian situation.) It does not mean that the culture-specific poems and post-modern poems are mutually exclusive. It will be more correct to say that his poems are post-modern, nay twenty-first century poems, among which culture-specific poems also occur.

Beginning from his earliest poems, Jiban blends his cultural experiences with a modernist sense of nostalgia and ‘the everyday’. ‘Farewell’, which features in his second collection in English translation, The Orange Hill, is a sample, noted for its poignancy brought about by the economy of words and deployment of accurate images.

Farewell (Biday)

Translated by: Lyra Neog.

On the day our sister left our home

She left an unbearable emptiness there.

Because she loved to sing alone

A room of her own was built.

The sad resonance of her singing

Scattered in the room

Hurts us now and then.

With the boy she loved

She left us forever—that is the custom,

But not very easy to accept.

Because she loved the simalu* blossom

She never told a lie to the river.

And the day she sailed downstream

Her sorrow began growing.

(*A kind of tall tree with red flowers)

‘Ninaam’s Dream’ (translated by Pradip Acharya), published in The Orange Hill appears to be one of his earliest masterpieces. The vivid images of the poem weave a mosaic, clearly speaking of the narrator’s disillusionment and frustration. It is understandably local and culture specific. It opens thus:

The doves stuff their crops full

Of grain sown for us by Abutani.

Don’t you eat till your crops fill

It will stop Ninaam dreaming.

The midwife says:

“Your Ma is gone.”

“You’re some liar. I have just done

Sucking her breast.”

The midwife says:

“Your homestead is burnt out.

Your father left early in the morning

To watch over the field of grain.

He is not back as yet.”

She weeps.

The midwife says:

“Your father was swept away

While having a palmful of water from the Obnori

He was swept away.”

She cries, and crying,

Digs the dream.

Digs the water of the Obnori….

Another of Jiban’s poem in The Orange Hill ‘Mother and Virginia Woolf Conversing at their Sick Beds’ directly addresses the issue of modernism and post-modernism in the Indian context and the western context. The Indian mother begins the dialogue addressing Virginia Woolf, commenting that by writing A Room of One’s Own and then committing suicide, she had become death itself. Then, in the last two lines of the stanza, the poet utters the definitive, ‘what would you call it/mental disorder, feminism or modernism’, which places the western cultural bracket within which the so-called ‘free individual of modernity’ operates. The Indian mother goes on depicting the contrasting picture further when she quite plainly spells out differences, asserting that they were traditional for they plant the ‘lai’ seedlings, which the western-type moderns pluck and use in cooking various dishes ‘in prescribed pre-modern ways’. The old Indian woman then lays out the complete contrast:

‘I too have a room of my own

A husband and children

And a house full of grandchildren

My bone marrow is drying up

Am lying in bed with a “bain stoke”

I am in real pain but am looked after too

I still sip our traditional brew

Against the doctor’s orders

I haven’t written so am not dead

I plant lai seedlings so I do not commit suicide

Nor ever will, for my children and their grandchildren

End their prayer with om shantihi shantihi shantihi.’

The very first poem in the collection, The Orange Hill, ‘Krishnaleela Transformation’ is truly post-modern. Beginning with the form of the eternal divine lover, surrounded by gopis, you have the classical Krishna for a moment; however, for once, his maya goes horribly wrong as the river goes without water, and the dotting women burn up in their love-ardour and turn into ashes, and Krishna too follows suit. I am quoting from the translation by Krishna Dulal Barua:

Krishna doesn’t return from the waters throughout eternity

Throughout eternity does the Leela go on

The Leela has no beginning no end

Krishna too has no beginning no end

What has an end O’ Krishna

We await with the flame of lust lit in our hearts

Then die out burning

Burn out to ash.

He later blossoms as a flower, after emerging from the ashes:

I’m in fire

I’m in ash

Krishna is my name

I’m a flower blooming in the void.

However, in the next scene, he transforms into a charging tiger surrounded by tribal hunters, who do not recognise him even after he identifies himself and are bent on attacking him. Finally, when he reveals himself as the One extolled by Sankaradeva in his Bhagavata do the tribal people spare him. When nubile girls look for him among flowers, now Krishna is merely placed as an image on a computer screen, terrified of the mouse! A gradual erosion of Krishna’s power of Maya is visible in the three panels, ending literally in virtual fear! This beautiful blending of the mythical with the medieval bhakti era and spanning the present with its cyberlife, reversing the traditional to its ultramodern avatar, Jiban effectively captures in a hop-step-and-jump fashion all that is there in human cultural history till date!

A Symbolist discipline is discernible in the poem ‘Hathor Phool’, also included in The Orange Hill. A further analysis will be futile, as symbols and colours, and sometimes symbols as colours, define the texture of the poem. It finally looks like a painting.

The Hands that will be Flowers (Hathor Phool)

(Translated by Leela Neog Bora)

Everyone in the world

Can raise his hand to the sun

With stretched out fingers.

Under the shadows of millions of hands

In the shady ground

Will grow out thousands of flowers.

The sun will be the flower

And none will have any hesitation

In plucking the flowers white and blue

Of joy and sorrow.

Men are trees

The hands are flowers

The multicoloured hands stretched out

Towards the sky.

You will see the hands become kites

Merging in the sky

Blue in blue.

‘Fire-eaters’ too is a post-modern poem. It operates mainly through the metaphor of fire and the red flower it spawns. One can read several meanings like martyrdom, a noble cause, revolution, bright hope for a positive future, and so on. Yet, there is the bold statement that the spring does not come here automatically; someone has to initiate the process of bringing it over. The poem stands on its own – through the image of fire and its colour.

Fire-eaters

(Translated by DN Bezboruah)

A group of men who swallowed fire is waiting

On the other bank, we have ashes and more ashes.

Overstepping the ashes and piercing the earth

Is a flower that has blossomed all alone.

There is just one flower amidst the ashes

A very bright, red one.

These days Spring doesn’t come unbidden

To sooth the minds of people.

Spring breaks all rules to arrive, at its own whim.

My sons, learn to swallow fire and live

Look there: a group is practising just that.

‘The Story of a Family’, translated by DN Bezboruah, is another poem that can be categorised as post-modern. Here, a family of our times is presented in its bare ordinariness. The parents epitomise practical sense with a definite objective of success in life, while their young son is different. He is presented dramatically, through the opening section, thus:

A few poems are beginning to flower in the sun

But people haven’t realised it.

Suddenly a teenager sees the colours of the poems

And points them out to his parents.

The parents, failing to see any blossoms or colours

Rebuke the son sharply for fussing about pointless things.

But even the rebuke fails to dampen his spirit.

Instead, he keeps turning back to look at the flowering poems.

His parents quickly try to control him once again.

But he is heedless, and with his gaze fixed on flowers, butterflies,

Birds, trees, and woods,

His mind is getting estranged from his parents.

The parents feel that their young son is indeed foolish and useful for being a dreamer, and sums up their estimation of him, thus:

“My obstinate son!

Look at the car. Your peers are driving their parents

In their cars.”

He casts a quick glance at the faces of his parents

And lowers his eyes.

“Do you see now? Borua hadn’t spoken in vain:

“There’s no point bringing up children anymore.”

Quite so. Borua was very right.”

Some of Jiban’s later poems exhibit the wisdom he has gleaned through the years, as he matures into middle age. For example, his poem Mirror and Water’ in Anindita Kar’s translation, carry the following cryptic message-like stanza:

Since the day of gazing at one’s reflection in water

To carrying mirrors in handbags,

The custom of self-gazing continues,

and will continue,

as long as there are mirrors and water.

And the poem concludes with these lines:

Everyone is blind,

Only mirror and water see clearly.

‘Everything Is the Same. Everything Is Not the Same’ translated by Anindita Kar plays on the theme of memory and recall and the funny games nostalgia can play. ‘Everything is the same’ is the familiar nostalgic exclamation anybody would utter after a visit to one’s own land after a long absence. However, the discerning, sensible adult would admonish at the same instant with ‘Everything is not the same’. Look at these lines:

A tree in the village

has grown old like mother.

Like father and brother,

two trees died prematurely.

Here is a tree

our daughter’s age.

The tree my age

hunches through storms,

loses its branches,

but straightens itself again

with the hope of offering shade.

And the loaded concluding lines speaking volumes for the processes of history and the shortness of human memory, which makes time go cyclical:

Apparently,

everything is the same

Apparently,

Not everything is the same.

‘You Smell Like Ripe Corn’ is a love poem with a difference. It is totally laid out against nature and has little to do with an individual lover.

The beloved steps into the river, like a raindrop falling into the water. Then she dips and proceeds to climb ashore. And the poem concludes:

You step out of the waters wet

Your fingers are the scent of ripe corn—

I will harvest and store them in my barn.

I love you till

Men take the east, the sun the west.

Come, let’s carefully turn yellow

like the ripened sun.

‘The Loofah Blossom,’ translated by Anindita Kar, is a love-poem of another kind. It begins with a flute playing through the night-rain without stop. The poet, likening himself to a tiny sailboat drawn by the flute-song, yearns to touch the song as does the river water. Then the magic begins to unfold:

A rain-drenched glow-worm came to me and said:

Do you hear the flute

that plays through the rain?

I had gone looking for that anonymous flutist.

That is when the wind brought me to you.

Don’t tell anyone about my coming.

The wind will keep the secret.

If the sky gets a hint of it

it will spill the beans to the stars.

I will spend the night with you.

The pigment of the loofah blossom is on my skin.

Put out the lamp.

We flower in the dark.

Anvar Ali, in his interview with Jiban, in one of his questions, made the observation that Jiban was not ‘politically loud’ in his poetry and most of his critically acclaimed poems were those depicting “sensual beauties of nature, and yet,” in the poem ‘Orange Hill’, there is a very clear political overtone. Anvar Ali asked him what his political and aesthetic approaches to poetry were, to which Jiban gave an elaborate reply: Jiban observed that politics in poetry should be confined to “connotative undertones” and should be an “allusive irritant.” He went on:

“The human condition is evoked through various images, metaphors, symbolic nuances and I personally do not believe in opening up the poetic space for any such overstatement where politics take the better of poetics. All poetic endeavours except those passionately self-absorbing cannot remain detached from a political consciousness. The postcolonial destiny in our situation has been complicated with the growing conflicts, socio-political rifts, displaced communities brutally ravaged by floods, erosion and political gimmicks. How can serious poetry turn away from the burning issues? The metaphor of ‘orange hill’ may be cited as an example of how politics of violence and conflict do enter my canvas with a little touch of the surreal. Therefore, the poem, “Guest” paints a picture of the fear and terror created among the people during the conflict between the ULFA and the government.”

He then presented three poems, which he said were on political themes: “Aai’s Voice”, “Witness of the Naked Times,” and “When Someone Brings News.”

The Orange Hill

(Translated by Lyra Neog Bora)

The orange hill is rushing

With their young ones the pigs are screaming

The fire is flying its red flames

he red flames are devouring the tips of the trees

The pigs are running after the oranges

The men are running with bullets and blood.

‘Aai’s Voice’ is a little poem that needs no explanation or comments:

Aai’s Voice

(Aai: mother)

I have more faith in Aai‘s voice

than in religion.

That faith is deep as the ocean’s bottom.

That faith goes far as the farthest stars.

Aai’s voice soars higher than religion,

for religion is a slave to politics.

‘When Someone Brings News,’ translated by Anindita Kar, is a poem that springs a shocking surprise on you. Beginning with the mundane news of his mother’s pig in the farm delivering quite a litter and then the fact that the Colocasia growing in abundance in the pit signifies the dwindling of the pig population, the narrator goes on to describe how the pigs scramble terrorised as they witness a fox skinning a dead man among the Colocasia bushes. The poet wryly concludes:

Aren’t you scared

when someone brings news?

I, always, am.

‘Witness of the Naked Times,” translated by Krishna Dulal Barua, is more direct. In the opening two stanzas, the picture is very clear:

Let’s push off.

The rains are teeming down.

At such a heartless time

Romance doesn’t fit in.

Blood streams forth with the rain.

There were reports of crowd-scuffles in the town.

A curfew-like ambience.

So truly there were bullet injuries on many heads, thighs and legs.

The rains arrived after a long break.

The peasants’ eyes ached after watching the sky hours on end.

It was a downpour after a drought.

The villagers rushed to the fields to lay the sludge.

Just as the yoked bulls with the plough were about to be driven

A sight caught the eyes:

Two corpses half-buried in the mire!

The village raised a hue and cry.

The terrified rustic faces

Sneaked into their houses dumbstruck.

The people lit a light and huddled together.

But the terror didn’t move away

.……..

Before I conclude, I would like to specially mention Jiban’s love for Kerala and Keralites he expressed through a beautiful poem, which he spoke about in his interview with Anvar Ali, when the latter asked him specifically. The poem was titled: ‘A Fairy Tale,’ in which the nature, art, pop culture and even celebrated names of Keralites were mentioned. Jiban answered: “Before coming to the point of my personal contact and intimacy with my friends in Kerala I would like to mention with all humility that ‘A Fairy Tale’ is a poetic rendering of my emotional and literary attachment with the Keralites. Written in the metaphor of a travel the poem engages itself in a cultural and literary dialogue. It’s my pleasure to share with you that Prof. Prabhat Bora, one of our most erudite critics, praises the poem as the perfect rendering of surrealist images which is a unique case in Assamese poetry. For me it is a recognition of my intimate connection with your land and people. Had I not been a poet this bonding wouldn’t have been possible, and I believe that poetry can bring together people making them kindred souls.”

In conclusion, I wish to comment on Prabhat Bora’s observations on Jiban’s poetry. Bora writes –in the Introduction-(ii) to The Orange Hill – that juxtaposing Jiban’s work against his culture and traditions, throws significant light on this brilliant poet of our times. In Jiban’s early poetry, the northern Golaghat landscape and his roots in his native place find expression in the form of nostalgia, during his prolonged exile away from his natal surroundings to earn his livelihood. The memories of his childhood experiences are reflected in his later poetry also, but by now his horizons have become wider and his poetry more abstract. This abstraction is inevitable as his worldview evolves through age and experience. ‘The excellence of Jiban’s poetry lies in the freshness of his imagery, his vitality and his sensuality, his eloquently lyric-rich voice that he inherits from his Mising origin, and the appealing casualness of his style articulated in an intimate and rustic idiom’.

Jiban Narah’s poetry is a veritable response to the question as to how modernism, after-modernism and post-modernism operate in the Indian context, especially in the rural landscape outside the metropolises, cities, or towns.

Notes:

- I have based, parts of the poet’s biographical sketch and early poetry, on the biographical note I provided in the poetry blog Y ILF Samanvay. https://blog.ilfsamanvay.org/poetry/assamese-poems/

- The translation from the Assamese, of Jiban Narah’s answers to the questions posed by Anvar Ali, as quoted, was done by Dr.Kamal Saikia.