One day in 2013, I stepped into an academic campus, which was a cultural shock to me from the very first moment. It was terrible—I had never felt more emotionally confused and vulnerable. I felt deeply insecure and didn’t know why. In one convulsed moment, I discovered it was because I was on a campus filled with people but invisible to most of them. I experienced the brutal strength that society unashamedly possesses to make someone feel wanted in one place and others feel equally unwanted in that place—as if it is telling them with silent eyes, ‘You don’t belong here’.

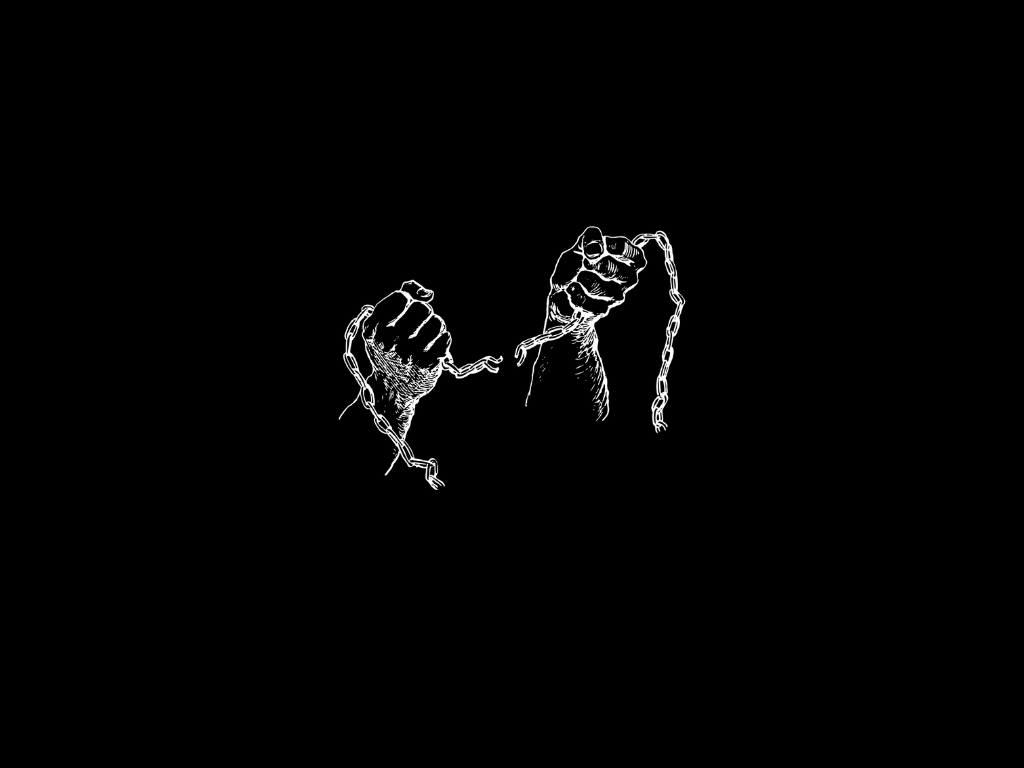

All of this happens without language at work or words exchanged. But the campus is where I learnt that the most oppressive society is the one which needs no physical weapon to destroy a person’s enthusiasm, dignity or personality. This society has for long made the oppressed see themselves as for society but not a part of it. He hardly sees himself as an equal part of such a society. An oppressive society has made him into an object that carries anti-liberation notions.

But such phenomenal moments also mark the beginning of a sense of inequality within society and an oppressed person. When an oppressed person like me, the first in my history, walks into a space of ‘knowledge’ traditionally and historically dominated and shaped by oppressors, his selfhood feels terrible. So much so that I would often struggle to find words to articulate emotions—also because the vocabulary for emotional articulation is shaped and dictated by the oppressor—and unknowingly engaged in self-deprecating behaviours.

Such is the emotional complexity of an oppressed person that he cannot even love someone who does not share his history without feeling jealous and consequently grudging the one he loves. But the campus is also a space for oneself. It is an unambiguous opportunity to make things work, to create scope for his liberation, which lies in discovering his selfhood and learning the pedagogy of the destruction of what he has been made into.

I was made by the history of my ancestors and its consequences into someone who always wanted something—and perpetually realised that whatever I wished for, willed and desired, was invariably inaccessible and unreachable. The questions shaped by the Dalit basti I was born in and the terribly depressing circumstances I grew up with meant that whether it was a material thing I desired or human affection, they were increasingly difficult to access. On top of it, the social realities inside and outside the Dalit basti completely erased my vocabulary to communicate with the world outside. More than envy, I felt a grudge against everything I wished for and desired but did not get.

I began to realise that the world has defined a role I would play but not provided the circumstances which could help me fulfil my dreams. I wanted to shout and scream, but my instinct told me that society would misunderstand that, too—and use it against me. As a Dalit, I knew that I understood words differently once I started reading. And I learnt that this difference is, more or less, my selfhood expressing itself. I knew I must live with it while I strived to destroy it in the long run—behind the construction of this selfhood also lies caste. And caste is unnatural, for it permanently destroys empathy and paralyses our ability to reason and grow, emotionally or in other ways.

My sense of the destruction of my selfhood started to sprout, as a seed turns into a sapling, when I entered an academic campus with people from all kinds of histories—of the oppressor and the oppressed—walked down the same roads, drank from the same water sources, and used the same toilets to shit and urinate. Despite these democratic participations, we all unapologetically protected ourselves. Shaped in the social isolation of our respective caste ghettos and gated communities, we arrived on the campus with no scope to develop empathy or love for each other.

Regardless of my limited sensibilities to grasp this truth entirely, as I tried to make sense of the cold-blooded weirdness of the world, I recognised my realisations were significant. No matter how bitter it is, the realisation of truth leads to deeper explorations. If something is true, one eventually reaches where one belongs, at its roots. And since I am uprooted, I must destroy my sense of uprootedness by following my small cognitive (essentially emotional) discoveries until I reach my roots.

If I was made into an ‘Untouchable’, if I was hated, unwanted, and discarded, the chances are that I, too, would adopt these traits unknowingly. I may want to hate, un-want and discard other people. I know I was treated indifferently, made into an Untouchable, and that, subconsciously, made me feel indifferent to others. From this vantage point of emotional transition, the pedagogy of destroying my selfhood involves developing empathy and love. But how, in a society with multilayered hate, indifference and divisions akin to a cold-blooded massacre?

Here, I am not only an oppressed person but also a male. I was not only taught to hide emotions and appear tough but made to feel vulnerable and inferior around members of oppressor castes. Historically, women from the oppressor castes could access water, but I (and girls or women of my community), was prohibited from touching the water in public places. In emergencies, we were served water from atop—so our touch would not pollute the server or the water. Does not caste then surpass gender in power equations?

This dimension adds to the emotional complexity of a male from an oppressed community in our caste-based system. It is also true, as Bell Hooks says in All About Love, that the “wounded child inside many males is a boy who, when he first spoke his truth, was silenced by paternal sadism, by a patriarchal world that did not want him to claim his true feelings”.

Here arises my need to explore the pedagogy of the destruction of my selfhood—the construction of caste. The oppressed must speak, even at the cost of being hurt and facing vulnerabilities. Spending years on an academic campus amidst people from every caste location, I could not feel connected with others. I avoided befriending people from my community, too, because it meant never leaving the emotionality of being oppressed or the perspective of it. So I chose—tried—befriending or acquainting myself with people from different caste histories. I never felt connected there too. I smoked joint after joint and drank all night with them, only to learn that humans are deeply intimate beings who want to break free from what holds them back or shackles them—but that does not mean everyone with these feelings is historically, socially or politically oppressed. When high or drunk, the members of oppressor castes aggressively manifest their need to break free and blabber about liberation and justice. But once they leave the campus, they enjoy privileged positions in existing power structures and multiply the privileges of their caste brethren.

Knowing each other is impossible without an intimate dialogue, even though the intimacy between people from opposite social locations can sometimes be really hurtful. Mostly, it leaves the most oppressed feeling deeply hurt and wounded.

On my campus, I was in love with three women from privileged caste histories at different times. Yet I feel I never understood them, although I never hid from them my angst, which is part and parcel of my identity. They knew who I was—am—but with their silence, they denied me access to their caste histories and wounds, if they had any. Despite feeling hurt, I knew that ceaseless dialogue in pursuit of empathy and love was my way towards learning how to destroy my selfhood. It is because my liberation lies in dialogue with myself and those historically involved in my subjugation. My dialogue was no meek attempt to make the oppressor hear me. No—it came from my realisation that violence is of no use to the oppressor or oppressed, for it ultimately dehumanises both to different degrees of its consequences.

My Self can be liberated from caste only when I accept hurt as a part of the dialogue and move beyond it. No liberation comes without wounds. My wound is my instinct to love, and I accepted it.