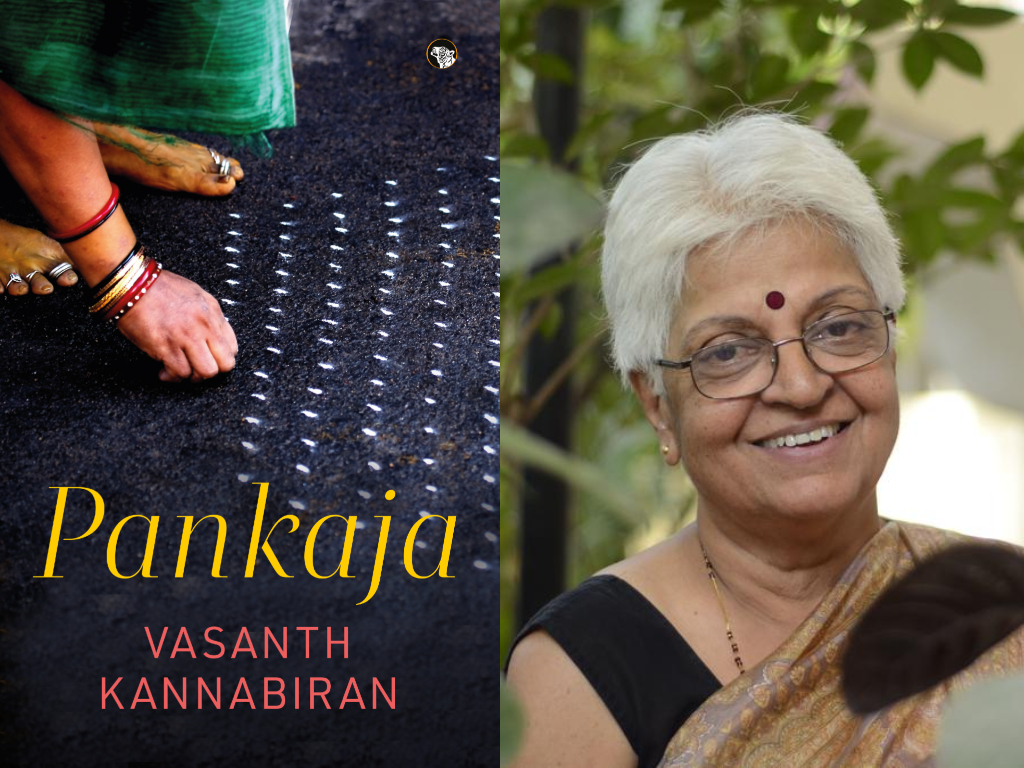

When Vasanth Kannabiran was growing up in the 1950s, grandmothers and aunts shared many real-life stories about ‘wives, widows and whores’ with her. In Pankaja, Kannabiran paints a vivid portrait of what it meant to be an upper-caste Hindu woman in India at the time. Pankaja’s life and the lives of her women friends and family members are all shaped by the institution of marriage; limited by the norm of wifely duty.

In this conversation with the Indian Cultural Forum, Kannabiran discusses playing multiple roles; writing in English; and what has changed in the status of widows from the period she writes about to now and more.

Indian Cultural Forum (ICF): On the oppression of widows, how much has changed from the period you write about to now?

Vasanth Kannabiran (VK): My focus was not so much on the oppression of widows, which has been dealt with in many writings, even in the nineteenth century. My focus was on the multiple ways in which women have circumvented orthodoxies — with reference to marriage, widowhood and tradition. It has always stunned me how women could manipulate these rules for survival. While many suffered, no doubt, the numbers that dodged these rules quietly was amazing. For instance, the anger against Muslims at that time seemed to be because they did not insist on virgin brides. I heard many stories of young widows simply eloping with Muslim men, hoping to lead a decent life. There are striking changes today, with educated and working women stepping out to remarry. And yet, the deep shame and stigma that haunted widowhood still lurk in the shadows. My concern was also that widows who remarried within caste and community married already married men with families, thus stepping into traditional settings through an unconventional act. In several instances, this created deep fissures within families — since it was not possible, structurally, to reconcile all the contradictions that arose. For instance, guilt, insecurities, the status of children (biological and stepchildren), the relative status of the wives, property and inheritance… Bigamy created problems, so women constantly struggled with a situation of heads you win, tails I lose. The experience of widowhood was trapped in this mire — and still, women held themselves together with little or no education and no property. These are the stories I have tried to piece together.

ICF: Have there been some milestones in the struggle?

VK: The milestones have been more in terms of violence against women — in the family and outside. And yet, with everything one thinks is a milestone, there is a millstone that weighs women down in myriad ways.

ICF: How do you, as a writer and an activist, see the possibility of bringing together class, caste and women’s movements?

VK: At one time, our slogan was that sisterhood was global. As an educated, privileged woman, I was forced to reckon with the realities and multiple oppressions faced by Dalit women, Muslim women and tribal women from both community and State. I re-learnt my politics – that struggle is rooted in social experience, and therefore solidarity must be based on this recognition rather than on abstract philosophy. There are crises and contradictions that we must address, no matter how difficult and complex. The experience of caste oppression — the viciousness of the privileged dominant castes and the rage of Dalits facing this violence on an everyday level — seems irreconcilable in the space of struggle. Revolution seemed a solution at one point but no longer. It is really frightening to think of what lies ahead. We thought we had grown older and wiser, but nothing is farther from the truth.

The days when women’s issues could be neatly grouped under dowry, child marriage, sati and violence are long gone. Today they are deeply political. Caste, transgender issues, majoritarianism, poverty, and livelihoods remain critical and difficult to identify. Women and activists of every hue are dogged by doubt, anger, and betrayal on the one side and the need to be global actors on the other. We unite, divide, despair, and reunite, demanding “justice.” I think there is hope for the future. There must be a point when we realise we need each other. In short, there are no simple answers.

Also read | An extract from Pankaja

ICF: As an activist and academic choosing to write fiction, could you shed some light on the different views of women’s issues?

VK: This is a difficult question. Once upon a time, we thought the word patriarchy provided all the answers. Then we moved to gender. Useful in analysing and theorising women’s oppression. Class, caste, race, age and sexual orientation simply multiplied the complexity of issues. But as we peeled off layer by layer, it grew increasingly complex. But we have no solutions. The State, policing, religion and cultural policing complicate the struggle for justice. The rhetoric is equality, but the practice is rooted in a patriarchal and discriminative culture. We are left with more questions. It is no longer possible to focus on women’s issues to the exclusion of the political climate.

When I write fiction, I am neither activist nor academic. I’m just a writer with a story that makes its own demands and lives its own life. I am not a tendentious writer trying to teach or set an example through my books. I want people to enjoy my story and say, “that’s so true,” or “this is so funny.” Pankaja is a patchwork quilt from tales I heard as a child. I realised decades later that they had a pattern. Women’s lives have a pattern, a meaning and a struggle.

ICF: Why did you choose to write in English?

VK: English has been my father tongue, the language of my intellect and imagination. All my reading has been in English. Though I also think and speak in two languages — Telugu and Tamil and understand Urdu and Hindi, English is the language of my intellect, the only language I write in.

ICF: Could you talk a little about the multiple roles you play — that of an author, a translator, an activist, and a writer?

VK: I don’t know whether these are multiple roles. I was an activist and still am because of my political beliefs. I became a writer and then a translator when I realised I had things to say to a larger audience. All these roles spring integrally from the needs and urgencies of the moment. All my work has been political so far. Beginning with the Emergency and International Women’s Year, I was catapulted into politics. And there has been no reprieve. I have indeed been fortunate to be part of so many struggles. And I have no regrets.