A woman’s cries punctuated the silence between the sounds of passing cars. It wasn’t high pitched or excruciatingly loud. It merely indicated the obvious, that someone was beating her up again.

The voice did not have a direction and did not last long enough to be followed. I did what I could – print posters with helpline numbers, and hope that I had distributed them far enough down the narrow lane that housed us both.

I contacted the closest helpline – women’s organization Jagori [Helpline numbers: +91 11 2669 2700, +91 8800 9966 40], to ensure their support in case someone did call in from my area. There was no other way to find her.

Soon after, I moved out of the cramped Delhi neighbourhood and forgot all about the sinking feeling of being a silent witness to abuse.

That is, until I was taken back to that role when I watched the recent Bollywood film Darlings.

Whispered conversations in the movie, between a beautician neighbour and her clients about the protagonist Badru’s screams while being abused, reminded me of my own involuntary participation in the common household experience of violence.

Also read: New Online Directory to assist victims of Domestic Violence to avert a post-pandemic crisis

Cycle and patterns of abuse

The film captured the cycle of abuse between Badru and her abusive husband, Hamza Shaik, with startling clarity. In the movie, Hamza alternates between promising Badru a better life and punishing her violently for not being a better wife.

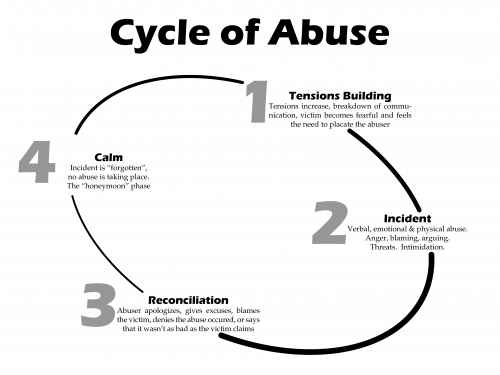

After all, the cycle of abuse theory was first published by American psychologist Lenore E. Walker in her book ‘The Battered Woman‘ (1979) based on detailed interviews with domestic violence victims. The social theory is now widely used to describe many kinds of abusive relationships.

She described four phases of abuse. The relationship cycles between the two worst phases of tension building (phase 1), which leads to the incident of abuse (phase 2). Following the abuse, there is a seemingly positive honeymoon phase of reconciliation (phase 3) and calm (phase 4), where things seem to normalize.

However, the more positive phases may not last long and as the abuse continues, it may reduce or even disappear over time.

In Darlings, Shaik may be characterized as a characterological domestic abuser, wherein he is clearly the perpetrator, and the violence is characterized by constant control and dominance, creating a life of fear for Badru. Another pattern is situational violence, which is considered less harmful, wherein either or both partners may respond negatively to situations like arguments.

In both cases, violence is a form of abuse and requires intervention. For the characterological variety, the only solution may be to leave and end all relations.

In the case of characterological violence, abusers may be further characterized by the pattern of abuse. For instance, American psychologists John and Julie Gottman characterize ‘pitbulls’ as jealous, domineering and tending to isolate their victims, whereas ‘cobras’ are psychopaths.

The movie also captured a more contentious aspect of the cycle of abuse, wherein abuse victims themselves become abusers. In a Harley Quinn-like move, Badru took matters in her own hands after a suicide attempt. She reversed the abuse narrative by holding her husband hostage.

While research on child-sexual abuse suggests that the numbers victims-to-abusers are limited, resistive/reactive violence by victims of domestic abuse and bidirectional domestic abuse are better documented, although many consider it an act of self-defence against the primary abuser.

Undeniably, abuse and violence begets abuse and violence.

In this scenario, it is unsurprising that domestic abuse has been in the news all over the world, from Hollywood stars and German football players, to the model American minority – American Asians, and Indian citizens in small towns and big cities. Evidently, the cycle of abuse continues to grip society in a deadly net.

Impact of COVID-19

It is hard to ignore that while the COVID-induced lockdowns protected the majority from COVID-19, women stuck in abusive relationships faced the brunt of being cooped up at home with their abusers.

While abusive family members had ample time to oppress vulnerable family members due to fewer or no work hours, the National Commission of Women (‘NCW’), which deals with domestic abuse in India, worked overtime [Helpline number: +91 7827170170]. According to NCW Chairperson Rekha Sharma, they increased the number of shifts to deal with the sharp rise in complaints. She stated that in 2020-21, the NCW received 26,513 complaints from women, an increase of 25.09 per cent, compared to the 20,309 complaints registered in 2019-20.

Most women complainants faced problems with living a life of dignity, as protected under Article 21 of the Constitution. A total of 6,049 women, nearly twice as many as the previous year, recorded domestic violence-related complaints. Other categories included cybercrime and dowry harassment.

A similar situation played out in many countries, prompting United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres to address domestic abuse during the lockdown directly, observing that: “Over the last week as economic pressures have grown we have seen a horrifying surge in domestic violence. In some countries the number of women calling support services have doubled”.

He urged all governments to make the prevention and redress of violence against women a key part of COVID-19 national response plans. The proliferation of domestic violence during the lockdown is now referred to as ‘the shadow pandemic’.

Also read: Responding to Violence against Women – The Shadow Pandemic During COVID-19

In India, pre-lockdown numbers of domestic violence were no less shocking. According to the 2018 National Family Health Survey by the Union Health Ministry, 27 per cent of surveyed women, that is, about every fourth woman, faced domestic violence since the age of 15 years. Women in rural areas faced more violence than women in urban areas (29 per cent and 23 per cent, respectively).

What chance do these women have in a society that normalizes being beaten and raped by their partners, husbands and other family members?

Lessons to be learnt from post-lockdown domestic violence

One cannot help but question, how it may be considered normal to lock up a woman in a container, film her cleaning her own excreta, all for more dowry, as was the case with non-resident Indian Mandeep Kaur.

Or, whether it is normal for women to decide which well fits them all and commit group suicide, as a final show of togetherness in the face of unimaginable violence, as was the case with three Rajasthani sisters, two of whom were pregnant.

Don’t we all pay the price when women can only pluck up the courage to kill themselves, after suffering years of abuse in silence? After victims give up for good and end their lives, the community is left with the shame of having done nothing.

Kaur’s friends from the Sikh community are left in exactly this position. Community members continue to express their rage and shame on social media. Civil society organisations like United Sikhs (US-based toll-free Helpline Umeed, 1-855-US-UMEED/1-855-878-6333) have been demanding the release of her daughters (aged four and six years) from their abusive father.

They all wonder why she never spoke up.

Can anyone blame her for remaining silent in a culture that treats married women as ‘paraya dhan‘ – someone else’s wealth?

Kaur tolerated daily spousal abuse until her death, partially out of fear of lack of funds to raise her daughters and give them a good life. More simply, she was defeated by her poverty.

Also read: Domestic Violence as the Shadow Pandemic

Economic dependency

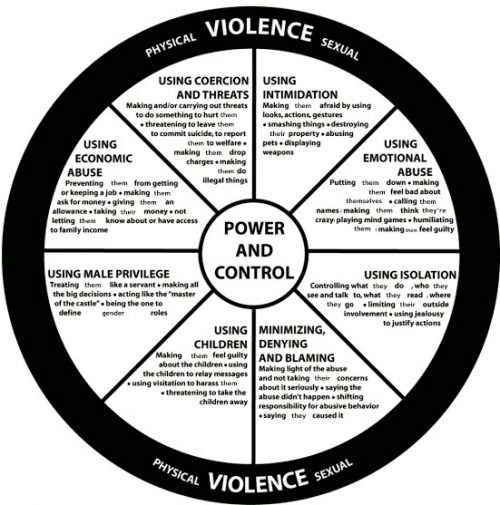

It is hard to ignore that domestic violence often includes economic abuse caused by economic dependency.

American psychologist Robert F. Bornstein describes economic dependency as the “degree to which one person relies on another for financial support, and is used to describe situations in which one member of a dyad has exclusive control over financial resources”.

Academic Priyanshi Chauhan observed in a 2020 study that approximately 22.5 per cent of married women did unpaid work for more than 70 hours per week, during the lockdown, and 30.5 per cent unemployed women witnessed the highest increase of unpaid work.

Economic abuse involves limiting or preventing the victim from accessing financial resources.

Bornstein notes that victims may have a hard time keeping a job or getting promotions and may be absent from work due to abuse related hospital visits. He points out that the linkages between economic dependency and abuse are bidirectional.

Specifically, economic dependency may force some women to tolerate physical abuse, and repeated abuse may lead to economic dependence. Thus, financial dependency is exacerbated by, and in turn exacerbates, the cycle of abuse.

In South Asian communities, it may also involve continued demands for dowry. In India, demands for dowry are so commonplace it is considered part of the package deal called marriage, both before and after the wedding.

Often, the victim is prevented from working to stop them from gaining control of their life. This creates forced dependency and a feeling of entrapment. Not only is the victim expected to remain silent, but also beg her abusers for necessary resources. Abuse is often about power dynamics, and controlling cash flows increases the feeling of disempowerment among victims.

For financially independent women, it may be possible to walk out of an abusive relationship – abused kids in tow.

However, even when the victims regain their independence and leave the abusive situation, they may be subjected to continued harassment, such as through expensive litigation, allowing economic and other abuse to continue.

Criminal law and gendered violence

While the contentious legal position on marital rape remains to be resolved in favour of victims, marital violence is a crime under Section 498A of the Indian Penal Code. It deals with the husband or a relative of husband of a woman subjecting her to cruelty, and covers cases of suicide and demand for dowry, among other things.

However, in the matter of Arnesh Kumar versus State of Bihar (2014), the Supreme Court diluted the application of section 498A, observing that it was used as a weapon by disgruntled wives, rather than as a shield. Now, it is up to police officers to decide on the arrest of someone accused under section 498A. This is where the law falters in its duty towards victims.

The Supreme Court was more sympathetic about potential harassment of husbands and relatives than towards genuine victims. It laid down guidelines for police officers that such arrest must be based on a reasonable satisfaction with respect to genuineness of the allegation, and cautioned magistrates not to authorize detention casually and mechanically.

The presumption that false cases are more harmful than the denial of First Information Reports (‘FIR’) in genuine cases creates a situation where social workers and domestic violence survivors are discouraged from filing a complaint by police officials, who focus on compromise and counselling.

One can’t help but wonder if the Supreme Court would reassess its sympathies in light of the rise in domestic abuse during the COVID-19 lockdown.

Even when the FIR is filed, it may be used for ulterior motives, like ‘love jihad’ – the politicized issue of religious conversion. A similar situation plays out in other cases of gendered violence like sexual harassment.

Caste is often used to deny victims of gendered violence FIRs and justice. Grassroots activist, researcher and trainer on social issues Aloysius Irudayam S.J., lawyer and researcher Jayshree P. Mangubhai and American academic Joel G. Lee interviewed 500 Dalit female victims of domestic violence for their 2012 book ‘Dalit Women Speak Out: Caste, Class and Gender Violence in India’. Only 13 per cent of the interviewees got their cases registered, and only 0.1 per cent received justice. 17.5 per cent of the women were actively turned away by the police.

Also read: Understanding contemporary sexual assault in India from the lens of the caste system

In a 2006 study by the same authors, Dalit Women Speak Out: Violence against Dalit Women in India, of 500 Dalit women who were interviewed, nearly half (43 per cent) had faced domestic violence.

In a more recent study by academic Sourav Chowdhury, Aditya Singh, Nuruzzaman Kasemi, Mahashweta Chakrabarty and Tribarna Roy Pakhadhara, information on 11,076 married Scheduled Caste (‘SC’) women from the National Family Health Survey-4 was analysed to find that 40 per cent of married SC women in India suffered from spousal domestic violence.

The legal pathos isn’t surprising considering that those in-charge of law enforcement may themselves be abusers.

For instance, a viral video from 2020 showed a senior police officer physically beating up his wife. When questioned by the media, his answer was: “This is a family dispute, not a crime.”

Even women are not exempt from callous attitudes towards domestic violence victims. M.C. Josephine, then chairperson of the Kerala Women’s Commission, participated in a live interaction on television, where a caller reported being subjected to domestic violence and not having told anybody, not even the police. Her response was: “Oh, then you suffer!“ (Translated from original Malayalam)

Unsurprisingly, it has been found that there is systematic under-reporting of incidents of domestic violence in 70 per cent of Indian states. The most underreporting may be in Bihar, Karnataka and Manipur, where the prevalence of domestic violence is around 40 per cent, while reporting is less than 8 per cent. At an all-India level, nearly 75 per cent of women who reported facing domestic violence did not seek help from anyone.

Also read: The COVID-19 impact on women in India: increased material and physical violence

Civil remedies

Economic, physical, mental and sexual abuse are all recognized as aspects of domestic violence under the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 (‘DV Act’).

It also provides a wider definition of domestic relationship as “a relationship between two persons who live or have, at any point of time, lived together in a shared household, when they are related by consanguinity, marriage, or through a relationship in the nature of marriage, adoption or are family members living together as a joint family”.

Section 3 of the DV Act defines domestic violence as any act that “(a) harms or injures or endangers the health, safety, life, limb or well-being, whether mental or physical, of the aggrieved person or tends to do so and includes causing physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal and emotional abuse and economic abuse; or (b) harasses, harms, injures or endangers the aggrieved person with a view to coerce her or any other person related to her to meet any unlawful demand for any dowry or other property or valuable security; or (c) has the effect of threatening the aggrieved person or any person related to her by any conduct mentioned in clause (a) or clause (b); or (d) otherwise injures or causes harm, whether physical or mental, to the aggrieved person.”

The DV Act is chiefly a civil remedy that is often used to obtain monetary relief under Section 20. Section 10 of the Act provides for services, such as shelter homes, medical aid, aid from protection officers and legal aid. However, it expects the abused woman to file for compensation, which can take months to come through, if at all, and leaves her financial security in the hands of the abuser.

This is akin to the age-old marry-your-rapist law that allowed rapists to escape prosecution by marrying their victims, which is still available as a legal remedy, especially in Middle Eastern and Latin American countries.

The Supreme Court has also spoken against such regressive practices, observing in Aparna Bhat that sexual abuse cases cannot “be remedied by way of an apology, rendering community service, tying a rakhi or presenting a gift to the survivor, or even promising to marry her, as the case may be.”

Also read: Indian Courts need to be Gender Sensitised

Perhaps it is time to reconsider whether sending a domestic violence victim back to her abuser for shelter and financial support can be considered a sustainable solution. Meaningful alternatives must be given due consideration.

Economic situation of women

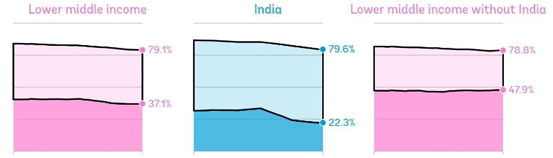

Economic empowerment of women is discussed by public policy professionals and lawmakers, ad nauseum. It is still a pipe-dream considering how low the female labour force participation rate (‘LFPR’) continues to be in India. LFPR is defined as the percentage of persons in the labour force, that is, those who are working, seeking or available for work, in the population.

According to the World Bank, the gap between male and female labour force participation in India is 57 per cent. With 20.8 per cent female LFPR in 2019 (of females above the age of 15 years), the World Bank found that India brought down the total female LFPR of lower-middle income countries, which had the largest gender gap as a group, by as much as 10 per cent.

The massive gender gap is confirmed by India’s latest Periodic Labour Force Survey 2020-21, conducted by the Union Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. According to it, the estimated Worker Population Ratio (‘WPR’) for males and females was 73.5 per cent and 31.4 per cent respectively, for ages 15 years and above. WPR is defined as the percentage of employed persons in the population.

The Supreme Court has also observed the gender gap between working men and women in the matter of Lt. Col Nitisha versus Union of India (2021), and remarked: “Presently, adjustments, both in thought and letter, are necessary to rebuild the structures of an equal society. These adjustments and amendments, however, are not concessions being granted to a set of persons, but instead are the wrongs being remedied to obliterate years of suppression of opportunities which should have been granted to women”.

From dependency to empowerment

Against this backdrop, three primary barriers to economic independence impact domestic violence victim’s participation in the labour force: (1) Persistent abuse and intentional damage by the abuser, such as, for example, stalking and harassment on the way to work and during working hours; (2) Health impairments brought on by the violence, including injuries, depression and anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and cardiac conditions; and (3) Structural obstacles, including precarious employment, lack of occupational training, family dynamics and cultural norms.

A fourth barrier emerged during the COVID-19 crisis, where staying in was not equivalent to staying safe for women who were forced to spend long hours with abusers, without adequate access to law enforcement and social services.

The socio-legal system is currently designed to fail victims of domestic abuse, thanks to dilution of laws like section 498A, patriarchal and misogynistic application of the law, judicial denial of the seriousness of domestic violence and crimes against women, and low employment among women.

Thus, a broader solution needs to be set in place which looks beyond addressing only the domestic violence incident, to including the causes that send women back to abusers. Apart from emotional dependency, primary among these is economic disempowerment of women.

As the Mandeep Kaur tragedy indicates, any meaningful solution for domestic violence victims must include economic empowerment to prevent sending victims back to the abuser, even if it is for maintenance under the DV Act, by providing meaningful alternatives.

With spending on women having decreased in the 2022 Union Budget, the resources available to women become all the more precious. If budgetary allocations include a serious effort towards economic empowerment through emergency financial aid for victims of domestic violence, as well as long-term solutions, through training and educational programmes, to enable economic independence, then we may be able to kill many birds with one stone.

Also read: Social Sector Given Short Shrift in Budget

Domestic violence victims empowered with State support for their economic independence can increase women’s LFPR, and decrease overall gender inequity by supporting one of the most marginalized and disenfranchised sections of society – unemployed victims of domestic abuse.

Psychological counselling for abusers, to deter them from further abuse, has been provided under Section 14 of the DV Act. This should also be extended to family members to enable a supportive environment for victims, which remains a blind spot.

Other promising solutions include gender sensitization from an early age for both sexes as well as parents. The same applies to judges, law enforcement officers and other stakeholders. Supreme Court guidelines in the Aparna Bhat case mandating gender sensitization for judges also remain to be implemented (as the Civic Chandran bail orders demonstrate).

Also read: Imperfect victim and perfect accused: Judicial stereotypes in Civic Chandran versus State of Kerala

Considering the extent of prevalence of domestic violence among Indian immigrant communities, it may also be time to extend meaningful consular support beyond Indian borders.

Such solutions must impact entrenched beliefs that justify violence. For instance, the National Family Health Survey-3 from 2005-06, reported that 54 per cent women and 51 per cent men agreed that it is justifiable for a husband to beat his wife. Similarly, a 2011 report by the non-profit organization International Center for Research on Women found that 65 percent of Indian men surveyed believed there are times that women deserve to be beaten.

The buck for handling domestic abuse need not stop with the government and courts. Non-governmental organizations and civil society groups have long fought for the rights of victims. It may be time to expand from victim-centric narratives, to include solutions that address abusers and those who justify abuse, beyond jail-time.

We also have a role to play, as the public. Perhaps, if we all did our bit, distributed enough posters, and dealt with the cycle and patterns of domestic abuse in our communities, women in Badru’s situation may receive enough help to live better and more productive lives.